It was just another 911 call to an apartment building where a tenant was causing a ruckus.

But when police arrived they found a distraught woman adamant that she could not go into her apartment: There were horrible things in there, she told them.

It was clear to the officers there was nothing untoward in the suite — the women was clearly unwell and experiencing a break from reality. The horrible things, though no less fearsome, existed only in her head.

The officers searched the place anyway.

“I’m sure they knew there weren’t bad people in her closet or under her bed, but they searched her whole apartment for her,” says Jennifer Chambers.

“Then she felt okay.”

That “creatively nice” solution was an example of the countless positive police encounters with individuals in crisis — ones we rarely hear about.

As co-ordinator of Toronto’s Empowerment Council, Chambers advocates on behalf of psychiatric patients and people with mental illness. She’s spent years working with police to improve their training so they can cope better when encountering people in crisis.

Chambers also sits on the Toronto Police Services Board’s mental health subcommittee, which makes recommendations to police and is now reviewing how best to act on recommendations from Justice Frank Iacobucci.

And she gives credit where it’s due: Toronto Police “do many many thousands of mental health calls a year,” she notes. “And most of them do not have a terrible outcome. So they have to get credit for that.”

But there’s plenty of room for improvement.

That was driven home this week after police shot to death a man reportedly armed with a hammer in Toronto’s west end.

Read the series:

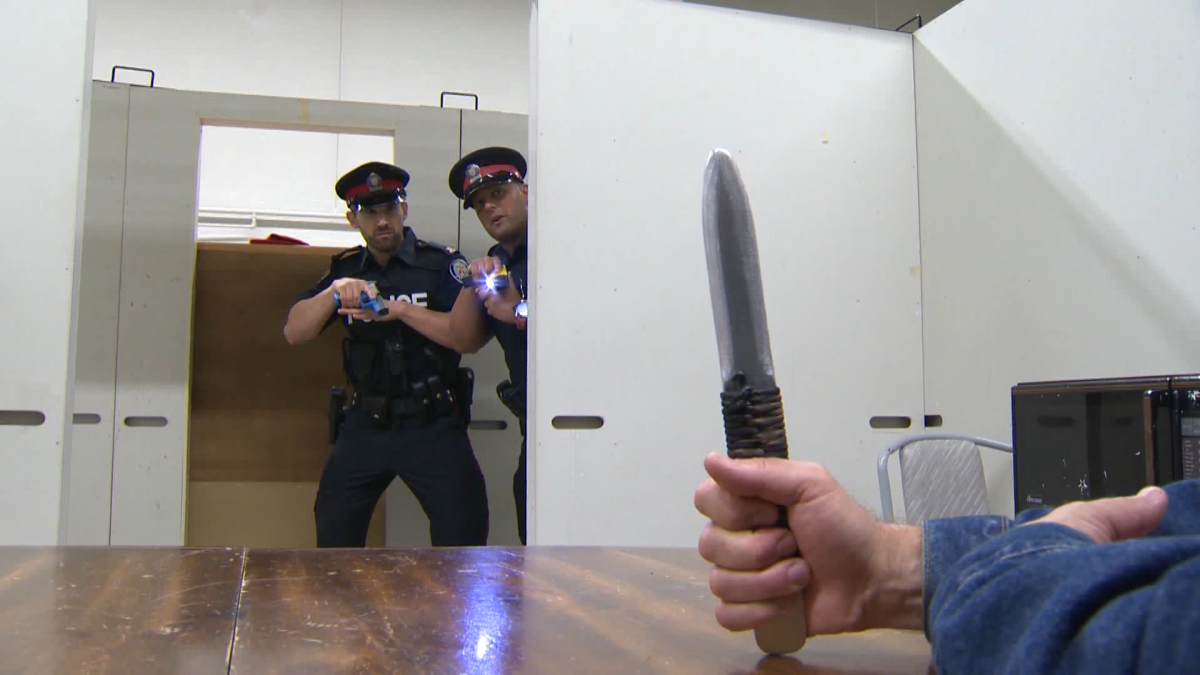

How should we police Taser use?

What we found from 594 pages of Taser incident reports

What happens to you when you’re Tasered

“Emotionally Disturbed Persons” — people in crisis, with mental illness — comprise more than half of individuals on the receiving end of Toronto Police Tasers. About a third of those individuals are apprehended under Ontario’s Mental Health Act, which allows people to be taken for psychiatric assessment against their will.

Chambers is on the front lines of those seeking to make police encounters with people with mental illness less awful, less deadly experiences.

Get weekly health news

The reviews she gets from people she talks to, and the results she sees from years of advocacy, are mixed.

For a decade, Chambers said, she arranged police officer training that included face-to-face contact with people with personal experiences of mental illness. That changed when police wanted more consistency and took over the training themselves.

Toronto Police say mental illness is part of officers’ annual two-day recertification training. That includes de-escalation and rapport-building; crisis negotiation and empathetic response. Officers are shown and discuss videos of people discussing their “lived experience” with mental illness and their interactions with police, but there isn’t any in-person interaction with people who have mental illness.

But you need to meet the people you’re trying to understand, Chambers argues. “They’re still missing that very important connection.”

WATCH: How do you train cops to deal with crisis?

Toronto’s Mobile Crisis Intervention Teams expanded to encompass the whole city last year. But their hours remain limited.

“Just having some teams that work in some areas a certain amount of hours a day, we don’t think that’s sufficient,” said Sukanya Pillay, counsel and executive director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

The issue goes beyond the Police College classroom to cop culture that often prizes machismo and sees mental illness as a weakness — even within the force itself. A Global News investigation into first-responder post-traumatic stress disorder found many officers suffer in silence, fearing the stigma of admitting their illness.

“There’s some kind of police culture that sort of counteracts training,” Chambers said.

“Certainly there’s an impression that police training has more to do with control than conversation.”

Part of the challenge, Chambers said, is that the behaviour of people struggling with serious mental illness can seem erratic, alarming or even dangerous.

“The more different someone seems from an officer, the more unpredictable they seem, the more dangeorus they seem.”

It doesn’t help that there’s still a widespread misconception that people with mental illness are violent or pose a threat to others, even though they’re much more likely to be the victims of violence than perpetrators.

“Society has very negative perceptions of people with mental health issues, and the reason for that is the fear of violence,” said , Uppala ChandrasekeraDirector of Public Policy for the Canadian Mental Health Association’s Ontario branch.

“Police officers … live in the same society, with the same stereotypes.”

Toronto Police Board Chair Alok Mukherjee has said he’d rather police spend their limited resources on better training for officers in dealing with people who have mental illness, rather than Tasers at several thousand dollars each.

READ MORE: Re-imagining Toronto cops

WATCH: How do you recruit police who double as social workers?

Deputy Police Chief Mike Federico says the police force is already doing that.

“We have a rich tradition of recruiting members to the organization who have a record of community experience,” he said.

“We’re focusing on the applicant who’s had a rich life experience, with the intention, of course, of capitalizing on that when they’re police officers.”

READ MORE: What happens to you when you’re Tasered

Tell us your story: Have you had an encounter with police while in crisis or struggling with mental illness? We want to hear from you.

Comments