TORONTO – Little maligned Pluto, the subject of the great planetary debate “Is it a planet or is it not a planet?” is readying for a visitor in just a short three months.

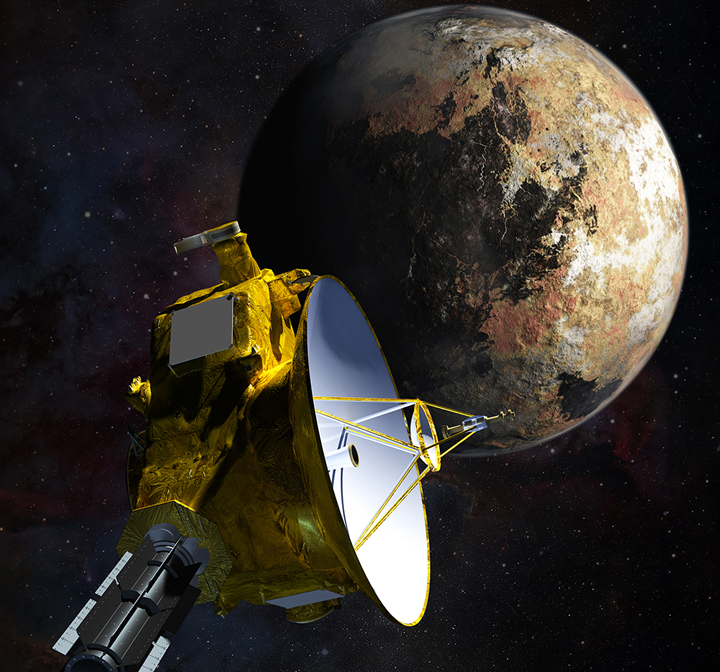

Discovered in 1930 by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, the tiny icy world at the fringes of our solar system, was reclassified (or “demoted” as many pro-Pluto folks will say) to a dwarf planet in July 2006 by the International Astronomical Union. However, just six months earlier, a planned mission to Pluto, called New Horizons, was launched from Cape Canaveral by NASA. It is scheduled to make its closest pass to the planet — er, dwarf planet — on July 14.

READ MORE: NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft releases new images of Pluto

And it really is a new horizon: not only is this is the first planned mission to the far off world, it’s the farthest planned mission of any space program.

New Horizons also holds the record for being the fastest spacecraft ever launched into space. And because it had to be fast (otherwise most involved in the program would be long gone) it won’t insert itself into orbit. Instead, it will make a flyby, coming to about 12,500 km from the surface of Pluto and about 28,800 km from its largest moon Charon.

It’s clear that those involved in the mission are anticipating the arrival of New Horizons. On Tuesday, NASA held a news conference about what the next few months hold for the mission.

And during the press conference, James Green, director of Planetary Science at NASA Headquarters revealed the first colour image of Pluto taken by New Horizons.

Why go to Pluto?

Get daily National news

Because of Pluto’s vast distance from Earth, we know very little about it. This mission plans to help astronomers and planetary scientists better understand the formation of our solar system and even Earth.

Our solar system is thought of as having three distinct types of planets. First you have the rocky bodies — Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Then the gas giants — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune (though Uranus and Neptune are also somewhat icy). And now, there’s the discovery of more far off worlds, which are called Kuiper Belt Objects or KBOs and Scattered-Disc Objects (SDOs). These are: Pluto, Makemake, Haumea and Eris. New Horizons presents the first opportunity to study these newly classified icy worlds.

“It’s the human race’s first opportunity to explore a new class of world,” William McKinnon, New Horizons co-investigator said.

What’s also interesting is that Pluto and its large moon Charon are sometimes considered a binary planetary system, or a pair of planets locked together.

McKinnon said that that’s somewhat similar to the Earth-moon system, in the sense that both of the planets’ (yes, dwarf planet) moons were believed to have been created by a large object crashing into them.

“We really are going to have a revolution in our knowledge,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator.

“We are flying into the unknown.”

Though New Horizons won’t be stopping at Pluto, Stern said that the imagery will be incredibly detailed. He compared it to being able to see New York City in detail from space.

But there is a caveat: we won’t be getting those images any time soon.

Because the spacecraft isn’t stopping, the main goal will be to collect as much scientific data — such as atmosphere, topography, surface temperatures and much more. That means forgoing sending any data back to Earth.

READ MORE: New names for Pluto moons; Vulcan neither lives long nor prospers

“In July we’re going to be hitting Pluto with everything we’ve got,” said Cathy Olkin, New Horizons Deputy project scientist. “It’ll be showtime.”

In fact, it will take 16 months for all the data to be sent back to Earth — right until October 2016.

“On closest approach date, we’re all going to have to be patient while New Horizon is exploring Pluto,” she said.

New Horizons is an exciting mission, and one that we haven’t seen in a very long time. The last time a spacecraft sent back the first images of a planet — Neptune — was Voyager 2 in 1989. There hasn’t been a planetary first in 26 years.

It may have taken 10 years to get there, but to the scientists involved, it’s been worth the wait.

“We’ve come such a long way, and we’re on Pluto’s doorstep,” said Alan Stern.

Cool Pluto facts

- Discovered by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930

- Is about 2/3 the diameter of Earth’s moon

- It takes 248 years to make a complete orbit

- Since its discovery, Pluto has never made a complete orbit

Comments