FREDERICTON – Imagine replaying the events of your day, over and over. Knowing that everything you did could mean the difference between life and death.

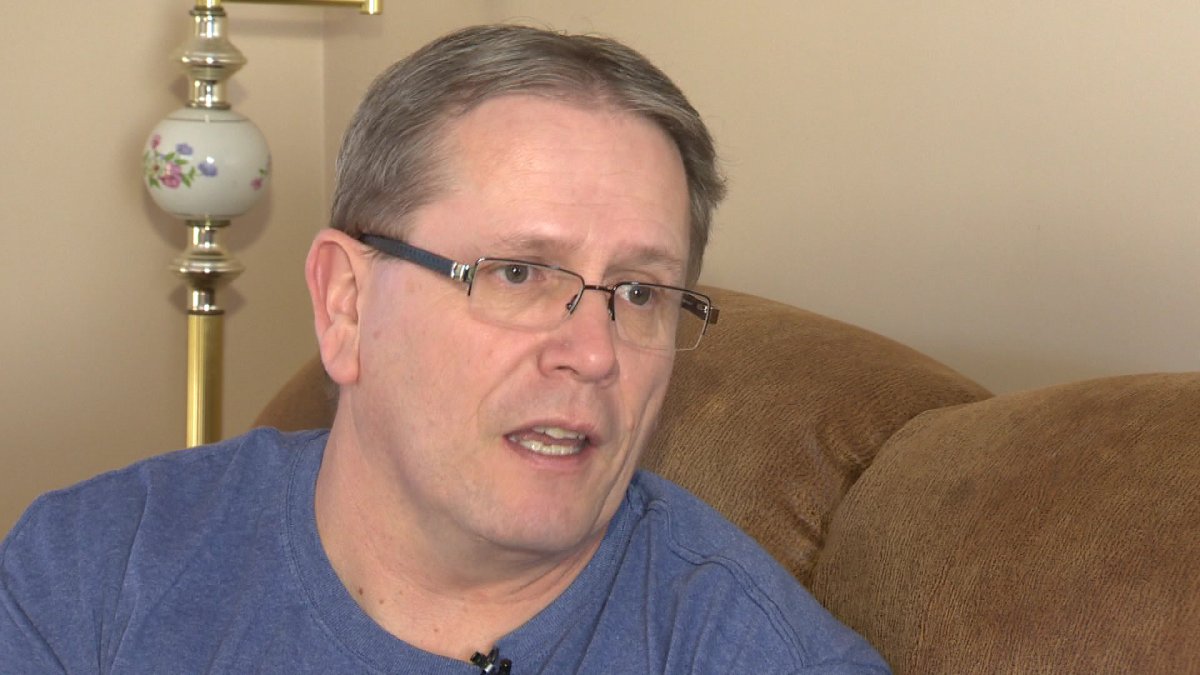

That was Dale Chase’s reality for more than 18 years. The Fredericton man used to work as a paramedic, but had to leave after nearly two decades of work.

“I guess the 18-plus years finally caught up to me. There were a lot of skeletons in the closet that kind of came forward,” he said. “Going through the system a lot of the times, it was after you had a bad call it was a ‘suck it up and move on’ type of attitude.”

Chase says he and his colleagues didn’t have the type of debriefing sessions that fire and police departments would get after a bad call. He would be able to talk about the incident with his partner, but there was no counselling, no way for him to deal with the trauma of his day-to-day work.

“I had some bad calls in the last five or six years that really haunt me, and keep haunting me.”

Get daily National news

And that build up can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. Counsellor Barb Wilkins says it’s not usually just one event that triggers PTSD.

“It’s more of a cumulative stress reaction,” she said. “First time it’s not too bad, second time may not be too bad, but there could be two or three traumas in a row that they don’t get the opportunity to process.”

Wilkins says because paramedics and first responders deal with traumatic incidents every day in a high stress environment, they are more susceptible to PTSD. She says employers need to help employees come up with a ‘self-care plan’ before they are put into active duty.

“It could be taking a walk alone. It could be talking to a colleague or family member. It could be seeking professional help, a mental health professional,” she said.

And without concrete plans and ways to work through trauma, paramedics feel helpless.

In a recent Canada-wide survey, 6,000 paramedics responded to questions about mental health. Of those who responded, 30 per cent said they had contemplated suicide, 70 per cent said they knew a colleague who had thought about suicide, and 79 per cent said they were worried about someone they worked with.

And Chase says he’s not surprised by those numbers. He said in his time on the force, he only spoke with representatives from the paramedics association once, and Ambulance New Brunswick frequently promoted a culture where employees did not speak about the tough parts of the job.

Now, Chase is still dealing with what he witnessed on the front lines.

“A large trigger for me is wearing work boots. I had an incident where I was at a call, and my work boots were a big part of the trigger. Baby’s milk. Yellow sleepers,” he said. “I had some bad calls in the last five or six years that really haunt me, and keep haunting me.”

Comments