OSLO – Leymah Gbowee confronted armed forces in Liberia to demand that they stop using rape as a weapon. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf became Africa’s first woman to win a free presidential election. Tawakkul Karman began pushing for change in Yemen long before the Arab Spring. They share a commitment to women’s rights in regions where oppression is common, and on Friday they shared the Nobel Peace Prize.

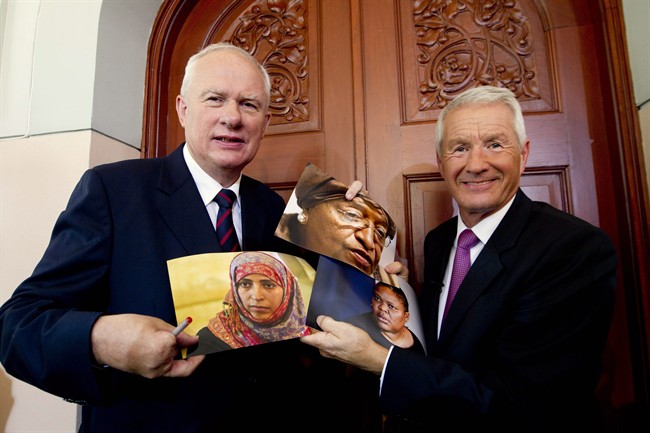

The Norwegian Nobel Committee honoured women for the first time in seven years, and in selecting Karman it also recognized the Arab Spring movement championed by millions of often anonymous activists from Tunisia to Syria.

Prize committee chairman Thorbjoern Jagland said it would have been difficult to identify all the movement’s leaders, and that the committee was making an additional statement by selecting Karman to represent their cause.

“We have included the Arab Spring in this prize, but we have put it in a particular context,” Jagland told reporters. “Namely, if one fails to include the women in the revolution and the new democracies, there will be no democracy.”

Karman is the first Arab woman ever to win the peace prize, which includes a 10 million kronor ($1.5 million) award that will be divided among the winners. No woman or sub-Saharan African had won the prize since 2004, when the committee honoured Wangari Maathai of Kenya, who mobilized poor women to fight deforestation by planting trees.

“I am very, very happy about this prize,” said Karman, who has been campaigning for the ouster of Yemen’s authoritarian President Ali Abdullah Saleh since 2006. “I give the prize to the youth of revolution in Yemen and the Yemeni people.”

Sirleaf, 72, won Liberia’s presidential election in 2005 and is credited with helping the country emerge from an especially brutal civil war. She is running for re-election Tuesday in what has been a tough campaign, but Jagland said that did not enter into the committee’s decision to honour her.

“This gives me a stronger commitment to work for reconciliation,” Sirleaf said Friday from her home in Monrovia, the capital. She said Liberians should be proud that both she and Gbowee were honoured.

“Leymah Gbowee worked very hard with women in Liberia from all walks of life to challenge the dictatorship, to sit in the sun and in the rain advocating for peace,” Sirleaf said. “I believe we both accept this on behalf of the Liberian people and the credit goes to them.”

Gbowee, who took a flight to New York on Friday, said she was shocked to learn she had won.

“Everything I do is an act of survival for myself, for the group of people that I work with,” she said. “So if you are surviving, you don’t take you survival strategies or tactics as anything worth of a Nobel.”

One of the first people she told was a fellow airline passenger.

“Sat by a guy for five hours on the flight and we never spoke to each other, but I had to tap him and say, ‘Sir, I just won the Nobel Peace Prize.'”

Gbowee, 39, has long campaigned for the rights of women and against rape, organizing Christian and Muslim women to challenge Liberia’s warlords. In 2003, she led hundreds of female protesters – the “women in white” – through Monrovia to demand swift disarmament of fighters who continued to prey on women even though a peace deal ending 14 years of near-constant civil war had been reached months earlier.

“You’re supposed to be our liberators, but if you finish everyone, who will you rule?” Gbowee asked rebel official Sekou Fofana during one march that year.

Gbowee was honoured by the committee for mobilizing women “across ethnic and religious dividing lines to bring an end to the long war in Liberia, and to ensure women’s participation in elections.”

Gbowee works in Ghana’s capital as the director of Women Peace and Security Network Africa. The group’s website says she is a mother of five.

She said that although she had never considered herself worthy of the prize, “women have important roles in peace and security issues and I think that this is an acknowledgment of that.”

“The world is functioning on one side of its brain” because women’s skills and intelligence are “not being used to advance the cause of the world,” she said.

The Harvard-educated Sirleaf took a different path toward change in Liberia, a country created to settle freed American slaves in 1847.

She worked her way through college in the United States by mopping floors and waiting tables. Jailed at home and exiled abroad, she lost to warlord Charles Taylor in elections in 1997 but earned the nickname “Iron Lady.” A rebellion forced Taylor from power in 2003, and Sirleaf emerged victorious in a landslide vote in 2005.

Even on a continent long plagued with violence, the civil war in Liberia stood out for its cruelty. Taylor’s soldiers ate the hearts of slain enemies and even decorated checkpoints with human entrails.

The conflict had a momentary lull when Taylor ran for office in 1997 and was elected president. Many say they voted for him because they were afraid of the chaos that would follow if he lost.

Though Liberia is more peaceful today, Sirleaf has critics at home who say she hasn’t done enough to restore roads, electricity and other infrastructure devastated during the civil strife. Her opponents have accused her of buying votes and using government funds to campaign for re-election, charges that her camp denies.

Liberia’s truth and reconciliation commission recommended that she be barred from public office for previously giving up to $10,000 to a rebel group headed by Taylor. Liberia’s legislature has not approved that recommendation, and Sirleaf has said that if she should apologize for anything it is for “being fooled” by Taylor in the past.

African and international luminaries welcomed Sirleaf’s honour. Many had gathered in Cape Town, South Africa on Friday to celebrate Nobel peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s 80th birthday.

“Who? Johnson Sirleaf? The president of Liberia? Oooh,” said Tutu, who won the peace prize in 1984 for his nonviolent campaign against white racist rule in South Africa. “She deserves it many times over. She’s brought stability to a place that was going to hell.”

U2 frontman Bono – who has figured in peace prize speculation in previous years – called Sirleaf an “extraordinary woman, a force of nature and now she has the world recognize her in this great, great, great way.”

Karman is a mother of three from Taiz, a city in southern Yemen that is a hotbed of resistance against Saleh’s regime. The daughter of a former legal affairs minister under Saleh, she has been dubbed “Iron Woman, “The Mother of Revolution” and “The Spirit of the Yemeni Revolution” by fellow protesters.

Long an advocate for human rights and freedom of expression in Yemen, she mounted an initiative to organize Yemeni youth groups and opposition into a national council.

On Jan. 23, Karman was arrested at her home. After widespread protests against her detention – it is rare for Yemen women to be taken to jail – she was released early the next day.

During a February rally in Sanaa, she told the AP: “We will retain the dignity of the people and their rights by bringing down the regime.”

Karman now lives in the capital, Sanaa. She is a journalist and member of the Islamic party Islah and heads the human rights group Women Journalists without Chains.

Jagland noted that Karman, 32, is a member of a political party linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist movement sometimes viewed with suspicion in the West. Jagland, however, called the Brotherhood “an important part” of the Arab Spring.

Yemen’s uprising has been one of the least successful so far, failing to unseat Saleh as the country descends into failed state status and armed groups take increasingly central roles.

The leaders of Tunisia, Egypt and Libya lost power following popular uprisings this year, but all three countries remain in turmoil. Hard-liners remain in control in Yemen and Syria, and a Saudi-led force crushed the uprising in Bahrain, leaving an uncertain record for the Arab protest movement.

Jagland noted that while it was hard to discern the leadership of the Arab Spring, Karman “started her activism long before the revolution took place in Tunisia and Egypt. She has been a very courageous woman in Yemen for quite a long time.”

Jagland called the oppression of women “the most important issue in the Arab world” and stressed that the empowerment of women must go hand in hand with Islam.

“It may be that some still are saying that women should be at home, not driving cars, not being part of the normal society,” he said. “But this is not being on the right side of history.”

Award creator Alfred Nobel gave only vague guidelines for the peace prize in his 1895 will, saying it should honour “work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

Last year’s peace prize went to imprisoned Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo.

___

Krista Larson in Johannesburg, Robert Reid and Sarah El-Deeb in Cairo, Jonathan Paye-Layleh in Monrovia, Liberia, Ed Brown in Cape Town, Ahmed Al-Haj in Sanaa, Yemen, Juergen Baetz in Berlin, Anita Snow at the United Nations and Meghan Barr and David Martin in New York contributed.

Comments