After over 30 years, the Kitsault mine is coming back to life.

The ghost town built for it isn’t.

Last month, Avanti Mining received federal and provincial clearance to begin work reopening the molybdenum mine, 140 kilometres north of Prince Rupert.

Avanti CEO Gordon Bogden says that workshops are scheduled in Terrace, New Aiyansh, and other communities as they prepare to begin construction next year. They plan to employ up to 700 people during the two years of construction and 300 permanent workers when the mine opens in 2017. At its height, the mine could produce 45,500 metric tonnes of ore per day.

“It’s moving in the right direction,” says Bogden, who says they’ve signed agreements with the First Nations groups in the area.

“We’re reaching out and engaging people. It’s a competitive market for labour, so we have to be proactive.”

Avanti plans to set up on-site accommodation camps to house the workers. That in itself isn’t newsworthy.

But it’s ironic when you consider the perfectly preserved town a 10-minute drive away – perhaps the most famous ghost town in all of Canada.

GALLERY: Explore the town of Kitsault, preserved for over 30 years

There had been campsites in Kitsault over the years, as companies mined whenever the price of molybdenum was high.

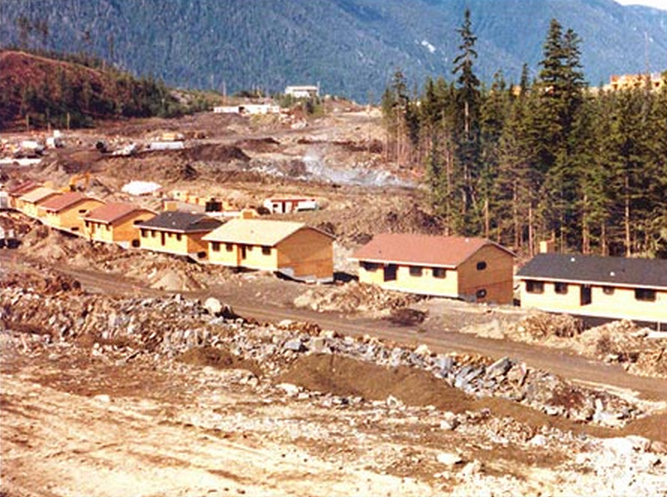

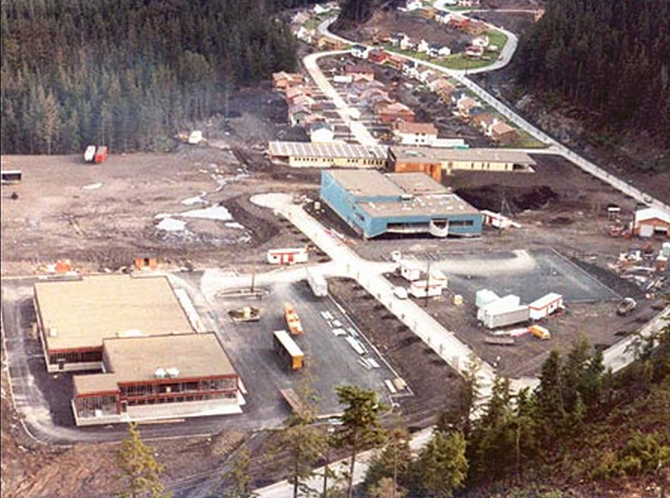

When Amax Canada announced they would reopen the mine in 1979, they wanted to avoid the perpetual problem of high employee turnover in remote B.C. resource communities.

The audacious solution? Build an entire town – one with the trappings of a large city, but for a population of less than 2,000.

Get daily National news

Costing around $43 million, Kitsault had a Sears outlet, sporting goods store, swimming pool, curling rink, movie theatre, and pub. There were single-family homes and apartment units. Racquetball courts and a hospital. Every effort was made to create a community that workers would want to raise families and retire in.

GALLERY: Kitsault as it was being built

And then, just as quickly as it had been built, the town was deserted. The price of molybdenum crashed once again, and 18 months after the town opened, Amax shut down the mine.

In most stories like this, the story ends with a freak fire destroying the town, or the structures slowly rot, eventually receding into nature.

Of course, Kitsault didn’t fade away. Amax employed caretakers to keep the town in fair condition, and when it was sold to American entrepreneur Krishnan Suthanthiran, he announced a full restoration of the town. Sewage and water systems were upgraded, buildings were renovated, and Suthanthiran talked about transforming the town into an eco-tourist destination.

The uniqueness of Suthanthiran’s plan – and the time capsule nature of the town – were irresistible to national and international media, who did several stories on Kitsault in the years to come. It’s kept interest in the town alive – along with the dream that one day, Kitsault may be a living city once again.

ARCHIVE: Global 16X9 travels to Kitsault to tell the story of the unique ghost town.

So why isn’t the opening of the mine resulting in the opening of the town?

“The Kitsault town never entered our plans,” said Borgen matter-of-factly, “so there was no reason to consider it as a housing option.”

The feeling is mutual.

“We’re not interested in the mine,” said Suthanthiran. “We don’t think it’s realistic, it’s not a viable project.”

Relations between Avanti and Suthanthiran have been chilly ever since Avanti bought the mine in 2008. A legal battle was fought over a statutory right of way across the town, which Avanti wanted to use for their mining activities. In 2010 the B.C. Supreme Court ruled in favour of Avanti, but the two have continued to spar since, with Kitsault commissioning a report claiming a mine could create damage to the town from acid rock drainage.

Today, Suthanthiran is pushing for an LNG terminal in Kitsault, saying the town’s deep-water port and existing infrastructure make it an ideal location.

“This town has been sitting empty for 25 years. We have to have the right project. It has to the an economic project that’s self-sustaining. I’ve been working for the last two years on the LNG angle, talked with investors, and this is something that will work” said Suthanthiran, listing Spectra Energy and TransCanada as companies that have expressed interest.

“What’s good for Canada is good for Kitsault.”

In the meantime, maintenance on the town continues. Suthanthiran says he gets dozens of requests every week to tour Kitsault, but isn’t interested in opening it up to tourists.

“Just because a lot of people are interested doesn’t mean it’s viable. We need to protect the security of the town. Tourism isn’t our business. It is not a historic site or museum that B.C. is funding,” he said.

So it goes for Kitsault, a town that grows more mysterious as the years go by.

“Ghost Town Mysteries” is a semi-regular online series exploring some of the strange sights from B.C.’s past.

The old trolley buses of Sandon

The swimming pool of Mount Sheer, B.C.

The stolen lightbulbs of Anyox, B.C.

Comments