WATCH: A Global News investigation revealed how violent life can be inside Canada’s psychiatric prisons. Jacques Bourbeau reports on those most at risk and the first steps to helping them.

Offenders are more likely to die or be violently attacked in a psychiatric prison than any other federal institution – by a long shot.

The people in these specialized facilities – in B.C., Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec – are the most vulnerable and problematic in a prison system already overflowing with mental illness.

And numbers obtained by Global News through an access to information request indicate they’re disproportionately subject to violence and death in the institutions supposedly designed to care for them best.

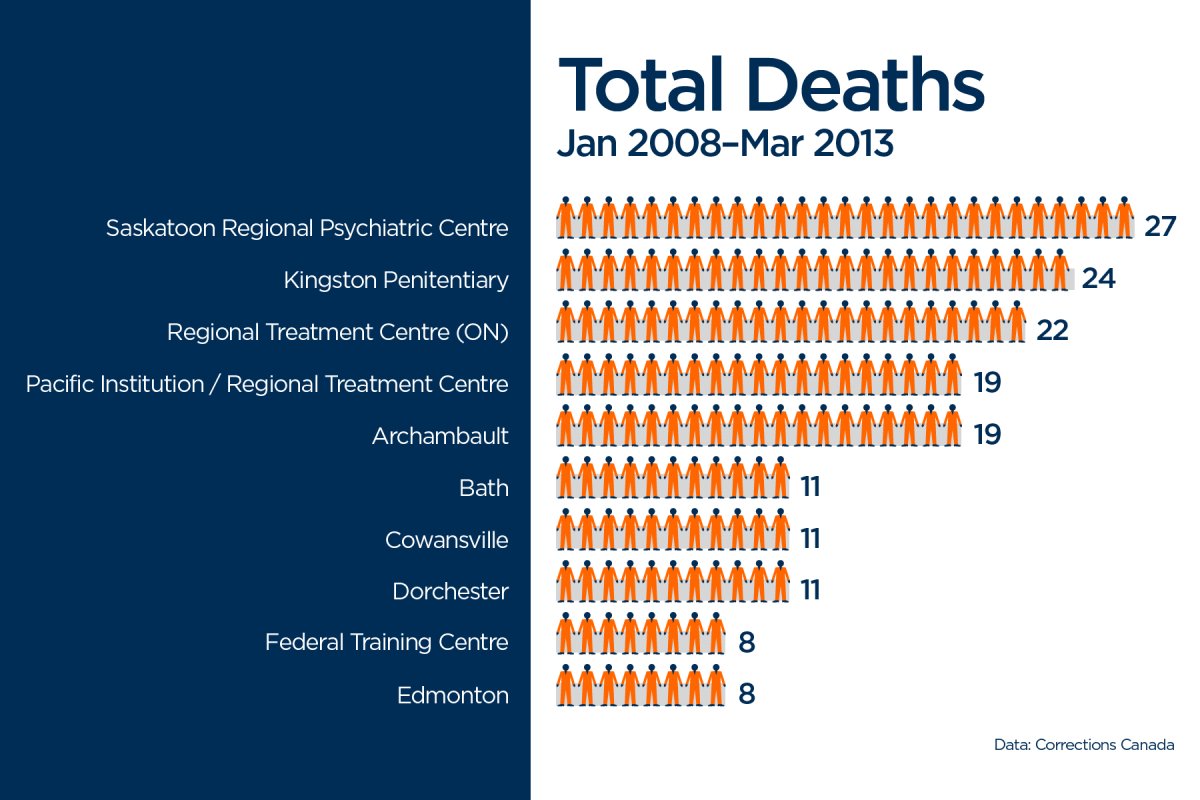

Saskatoon’s Regional Psychiatric Centre boasts more assaults and deaths than any other federal prison, even before you take population into account. The treatment centre attached to now-shuttered Kingston Penitentiary is close behind, as is a treatment centre in Abbotsford, B.C.

Three of the top 10 prisons for inmate deaths between January, 2008 and March, 2013 are psychiatric prisons – the Saskatoon Regional Psychiatric Centre, Ontario Regional Treatment Centre and Pacific Regional Treatment Centre – with an average number of deaths almost double other top institutions.

Factoring for prison population, inmates were 260% more likely to die in the Ontario Regional Treatment Centre than in Kingston Penitentiary next door.

(In the vast majority of cases we received, the cause of death was categorized as “Other.”)

This is where Corrections Canada sends its sickest, most vulnerable inmates – the ones they can’t deal with anywhere else.

“The system has no other place to – call it what it is – to warehouse them,” says Don Worme, a Saskatoon-based lawyer who has represented many inmates at the Regional Psychiatric Centre.

“I think we should be horrified as a society that this sort of thing persists,” he said.

“The public ought to be asking for answers.”

New strategy ‘ a good first step’

After a months-long investigation during which Corrections Canada refused access to any of these psychiatric institutions or their directors, and after Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney refused to speak to Global News on the issue, he has come out with a “Mental Health Action Plan” that includes, for the first time, participation in a plan that’s been on offer for years to house women inmates with serious mental illness in a specialized provincial facility.

Funny thing is, Corrections Canada already had a mental health strategy – one it unveiled in 2010.

“CSC has been working on implementing that 2010 strategy ever since 2010,” says prison watchdog Howard Sapers. “So there’s not a bunch new in this except the fact that the minister has made a point of saying, This is what we’re doing.’ And that creates a different level of accountability.”

Sapers called Thursday’s announcement “a good first step” but can’t help wondering: Why such a limited endorsement of a plan to put more inmates with serious mental illness in specialized care, when that plan’s been on offer for years? Why not abolish solitary confinement for these troubled offenders if we know it only makes their condition worse?

Just as irksome, he says, is that Corrections Canada has been delaying its response to concerns he raised a year ago, promising to address them when it responds to recommendations from the Ashley Smith inquest – in December, 2014.

Interactive: Explore deaths and assaults per capita in Canada’s federal institutions. Click a circle for details; double-click to zoom, click and drag to move around.

On one hand, it makes sense that the system’s sickest, most erratic individuals are more likely to die or become involved in violent encounters.

But the problem, physicians and advocates argue, is that despite these institutions’ extra medical resources – and additional cost of $50,000 a year per inmate, compared to maximum-security institutions – they’re still more prisons than hospitals. Their first responders are correctional guards who’ve taken a two-day workshop on mental illness, not health-care practitioners with certification and years of expertise.

And they still put inmates in solitary confinement even though the harm this does to people with mental illness has been documented and is driving drastic policy changes south of the border.

There are alternatives: Ottawa and Ontario have spent years sitting on an offer to help female inmates with serious mental illness in the same kind of institution that’s working with their male counterparts. This week, Corrections Canada made a preliminary move to implement it.

A recidivism revolving door

- ‘Shock and disbelief’ after Manitoba school trustee’s Indigenous comments

- Invasive strep: ‘Don’t wait’ to seek care, N.S. woman warns on long road to recovery

- Grocery code: How Ottawa has tried to get Loblaw, Walmart on board

- ‘Super lice’ are becoming more resistant to chemical shampoos. What to use instead

Canada’s crisis of mentally ill inmates is set to worsen if federal legislation cracking down on offenders deemed not criminally responsible makes defence lawyers more likely to take their chances with a traditional prison system that can’t handle them and where they won’t get proper treatment.

And when their sentences are up they’ll be released into the community, often no less likely to offend than when they first went behind bars (and sometimes much more so).

People with mental illness who’ve gone through the traditional prison system are twice as likely to commit more crimes on release than their psychologically healthy counterparts, says Alberta-based lawyer and psychiatrist Patrick Baillie.

Ottawa knows this is a problem: Internal Public Safety memos obtained by Global News acknowledge the crisis of mental illness in Canada’s prisons – there are too many, with problems too complex, for the system to deal with.

But the man in charge won’t talk about it.

Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney refused to speak with Global News for this story.

After two months of back-and-forth, his spokesperson said,

“It is not a practise for the Minister of Public Safety to comment on CSC operations. Therefore the interview is not possible.”

In a separate statement, Corrections Canada said it “takes the death of an inmate very seriously. In all cases where an individual dies while in custody, the police and coroner are called in to investigate.”

Blaney did address the issue in a press conference May 1, saying Corrections Canada is “very well aware” of the issue and plans to get more seriously ill inmates into more medical facilities.

NEXT: Canada’s sickest inmates, locked in its deadliest prisons

Comments