When Dave Sills and the Northern Tornadoes Project first began their work in 2017, they assumed they’d be gathering data to confirm their suspicions: that the Prairies are Canada’s hot spot for tornadoes.

Instead, they’ve been surprised to find that Ontario is now where the action is and that strong tornadoes have been developing later and later in the season.

With Environment Canada anticipating a hot summer and Natural Resources Canada predicting an “above normal” wildfire season, will the volatile summer forecast include more tornadoes? And where in the province are tornadoes more likely to develop?

A Goldilocks problem

There are different ways that tornadoes form, but the strongest are often generated through supercell thunderstorms, NTP executive director Sills said, but predicting tornadoes is extremely complicated.

“It’s kind of a Goldilocks problem.… That’s still a hot area of research. Sometimes you get two supercells next to each other. They look very similar. Why does one produce a tornado and the other one doesn’t? We still don’t know.”

At most, the potential for tornadoes can be predicted about three days out, but a seasonal prediction is not yet possible.

“It’s been a really big tornado year in the States this year. I don’t remember anybody saying that was going to happen. I don’t think that we’re at that level of the science yet.”

What is predicted for summer 2024 is a hot summer with above normal wildfire activity, which may impact tornadoes.

Natural Resources Canada’s Canadian Forest Service scientist Richard Carr said wildfire activity has been below normal in Ontario so far this year, but above normal severity (meaning more fires and/or more area burned than normal) is expected from now through August. Carr added that “much above normal” severity is expected in August along the Ontario-Manitoba border.

While more data is needed to confirm the hypothesis, NTP researchers have noticed a correlation between wildfires and tornadoes, with fewer tornadoes recorded amid “big wildfire” years. Sills believes the smoke from the fires stops sunlight from providing enough energy to thunderstorms to reach the intensity required for tornadoes.

Get breaking National news

However, Global News meteorologist Anthony Farnell notes that “tornadoes can also form along smaller-scale boundaries and lake breezes that often develop during the afternoon in southern Ontario.”

Such tornadoes often “spin up quickly and dissipate just as quick and are on the lower end of the scale.”

“The more heat and humidity in play, will often lead to stronger storms and bigger, more damaging tornadoes. This summer is predicted to be very hot and humid so the potential is there for an active tornado year as well.”

Canada's tornado hot spot

Because tornadoes are a relatively rare weather event, even though they happen every year, the standard for data collection is 30 years. In his previous work with Environment Canada, Sills said he led the development of a 30-year climatology of tornadoes from 1980 to 2009. The next climatology, from 1991 to 2020, was just recently completed.

The NTP, out of Western University in London, Ont., published a summary of new data last month, stating that Saskatchewan is no longer the province with the highest tornado frequency. The Prairie province had an average of 17.4 tornadoes per year in the 1980-2009 dataset, dropping to 14.6 per year in the 1991-2020 data.

In the most recent data, Ontario “leads Canada with 18.2 tornadoes per year.”

“But I really think that we need the next 30-year climatology, so that would be from 2001 to 2030 to be able to say… ‘There’s the trend,’” Sills said.

Where in Ontario are the most tornadoes recorded? Where the most severe thunderstorms are, Sills said.

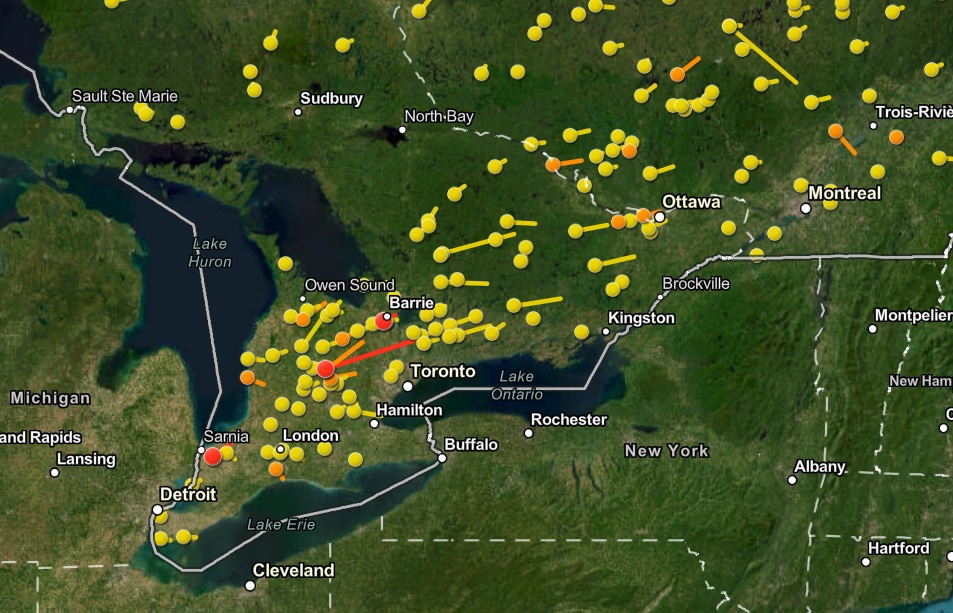

“There is a corridor in Ontario that goes from Windsor, Sarnia, north of Toronto to Ottawa. The Great Lakes have a big influence on where thunderstorms develop and where tornadoes can develop.”

Farnell seconded Sills’ assessment, explaining that while there isn’t any “tornado alley” in Ontario, “storms are more likely to produce tornadoes in a narrow swath from Windsor to Barrie.” In recent years, however, there has been an emergence of more frequent tornadoes around Ottawa but it’s “still too early to tell if this is a bigger trend or just an anomaly.”

Sills said there hasn’t been a single EF2 tornado or stronger in the Windsor region since the NTP began their work in 2017. Instead, the strongest tornadoes have been in the Barrie area into eastern Ontario and southern Quebec.

North of Lake Superior, however, there’s a “big hole” in tornado activity.

“The one place where tornado activity is mostly shut down is to the northeast of Lake Superior. It’s just so big and cold that it’s really hard for thunderstorms to develop there.”

From May to September

Historically, some of the biggest tornadoes in Ontario were recorded in May and June, including EF4 tornadoes in Sarnia in May 1953 and Barrie in May 1985 and an EF4 in the Windsor area in June 1946.

In the past 20 years, however, severe tornado activity has shifted later in the summer – July through September.

“There was an EF3 tornado that went through Dunrobin (Ottawa) and into Gatineau. That was September 21st, 2018.”

An EF3 tornado that struck Goderich in 2011 occurred in late August.

Why the season is extending into September is still unknown, but Sills theorizes the Great Lakes may be playing a role.

“If they have warmed — which is what I understand from the climate change studies and the modelling studies is that the Great Lakes have been warming — that can have an impact,” he suggested.

“When we looked at our neighbouring states, Michigan and New York state, they didn’t have that same pattern where things were shifting later. It was something peculiar to southern Ontario.”

- Tumbler Ridge B.C. mass shooting: What we know about the victims

- Trump slams Canada as U.S. House passes symbolic vote to end tariffs

- ‘We now have to figure out how to live life without her’: Mother of Tumbler Ridge shooting victim speaks

- Mental health support after Tumbler Ridge shooting ‘essential,’ experts say

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.