A Quebec man’s first-degree murder conviction in the death of a junior college student in 2000 has highlighted advances in DNA research that are being used to solve cold cases all over Canada.

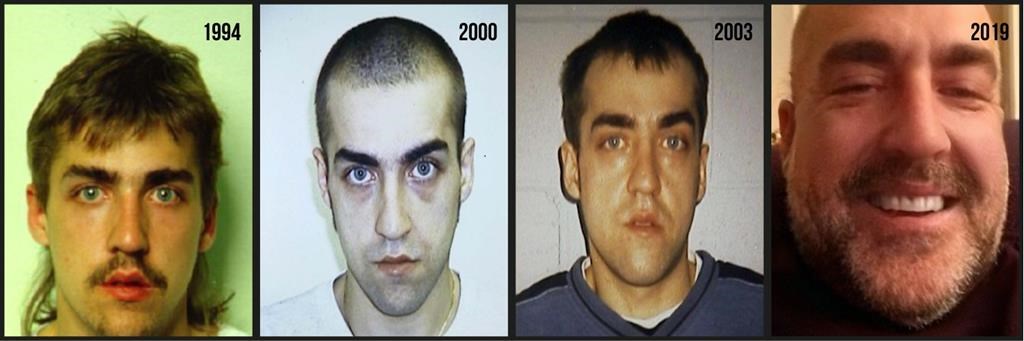

A jury took less than an afternoon on Tuesday to convict Marc-André Grenon, who was arrested and charged with killing Guylaine Potvin more than 22 years after the crime thanks to a DNA project by the provincial crime lab.

Michael Arntfield, a criminologist and professor at Western University, said the speed of the Grenon verdict “speaks for itself in terms of just how compelling this technique is.”

Arntfield said the use of DNA research to track suspects has been accelerating in recent years thanks in large part to the Toronto police, who obtained a government grant to accelerate use of the techniques in investigating cold cases across Ontario.

Previously, DNA samples left at crime scenes could only be compared to profiles in criminal databases. But with the advent of home DNA kits — delivered by companies who offer private genetic sequencing — researchers can compare crime scene evidence to DNA samples from thousands of profiles that have been uploaded online.

If researchers find a match between crime scene evidence and a DNA sample uploaded to a website — even if that match corresponds to a suspect’s distant relative — they can start to build a family tree, which provides a list of potential persons of interest that can then be investigated through traditional policing methods.

The Toronto police’s initiative “opened the floodgates” to reopening Canadian cold cases, and especially those with a sexual assault component, Arntfield said. High-profile successes include the arrest last year of Joseph George Sutherland, who pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree murder in the stabbing deaths of Erin Gilmour and Susan Tice in 1983.

In Grenon’s case, a forensic biologist told jurors that the suspect was tracked down thanks to a project that analyzes the Y chromosome of DNA samples and suggests potential surnames that could be associated with it, based on comparisons with DNA uploaded to public sites.

Get breaking National news

The biologist testified that DNA found under Potvin’s fingernails was inputted into the project’s database, which produced the name “Grenon.” Police then honed in on the suspect, whose name had surfaced early in the investigation, and tracked him to a movie theatre to obtain his DNA from a discarded cup and straws.

The same Y chromosome technique was used last year to help police in Longueuil, Que., south of Montreal, identify Franklin Maywood Romine as the person who likely raped and murdered 16-year-old Sharron Prior nearly 50 years ago.

After sentencing Grenon to life in prison, Quebec Superior Court Justice François Huot suggested that more convictions obtained by the use of DNA could follow. “Several individuals will sleep less well tonight after hearing the news,” he said.

Arntfield said that while cases are being solved, many of them still involve perpetrators who are dead, including Romine and Calvin Hoover, who was identified in 2020 as the killer of nine-year-old Queensville, Ont., girl Christine Jessop in 1984.

The first-degree conviction in the Grenon case could encourage police forces across Canada to move forward on their own cold cases, Arntfield said, although he added that investigators should be using DNA research techniques with or without a court precedent.

“You can’t sit around and wait for cases to be adjudicated before you decide to start acting on current emerging investigative techniques that have proven successful elsewhere,” he said, noting that the research often costs only a few thousand dollars.

While the techniques have proven effective in solving crimes, some civil rights groups have expressed privacy concerns. Canada’s privacy commissioner has said that while municipal and provincial police forces are subject to provincial laws, DNA is “highly sensitive personal information.”

“We recognize that DNA profiles can play an important role in law enforcement activity. However, use of DNA has significant privacy implications,” wrote Vito Pilieci, a communications adviser for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

“We would support strong oversight and monitoring by the (privacy commissioner) of the collection, use, retention and destruction of DNA profiles by federal police, particularly as it pertains to police use of genealogy databases compiled by DNA kit companies.”

Arntfield said the concerns over privacy can be allayed by ensuring law enforcement can only search databases composed of samples from people who have explicitly consented to their information being used in criminal investigations.

He dismissed the idea that an offender’s privacy can be breached by a DNA test taken by someone else that inadvertently reveals a familial link.

“That’s no different than saying it’s a breach of privacy that somebody’s neighbour called a tip into the police that they recognize their face from a composite drawing,” he said. “It’s just bad luck.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.