TORONTO – When a new disease emerges, scientists and physicians hope something that’s already in the medicine cabinet can be used to treat it.

A new study suggests for the novel coronavirus, that may be the case.

Scientists from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases are reporting that a combination of two existing drugs may be useful in treating the new virus, which has emerged from countries in the Middle East.

The cocktail is made up of a generic antiviral drug called ribavirin and interferon alpha 2b, a synthetic version of a protein made by the human immune system.

The work is preliminary; the drug cocktail was tested in two types of monkey kidney cells, not in live animals or people.

But virologist Vincent Munster, one of the authors, says testing in macaque monkeys is already underway and a scientific paper spelling out the results should follow this one shortly.

These initial results are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

That the researchers tried ribavirin comes as no surprise. The drug was widely used during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Then, as now, there were few antiviral drugs to resort to in the face of a new threat. Trying ribavirin made sense. The drug is used to treat hepatitis C.

“It was an obvious extension of the work that was done with SARS,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Osterholm, who was not involved in the research, praised the authors for putting the drug so quickly to the test. But he cautioned that success in cells in a Petri dish does not guarantee the drugs will work in people.

“It’s important information and hopefully it will be exciting information,” Osterholm said.

“At this point, however, translating … the bench research into actual human clinical benefit still has a long ways to go. And we can only hope that this is going to work.”

The first author of the study is Canadian Darryl Falzarano, a visiting research fellow at the NIAID’s Rocky Mount Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont., where the work was done. In an interview, Falzarano explained that though ribavirin had been used in SARS, it’s impossible to say if it was effective, because no clinical trials were done.

Doctors started to give the drug, hoping it would work. It quickly became the standard of care. Complicating matters was the fact that it was always given in combination with corticosteroids, so it is impossible to tease out if any benefits seen were due to ribavirin, the corticosteroids or the combination.

After Toronto’s outbreak was brought under control in July 2003, doctors here raced to draft a protocol for a clinical trial to test ribavirin, assuming as many did that SARS would return when winter weather ignited the next cold-and-flu season. But SARS never returned.

“Even though there were 8,000 cases and a lot of people treated, the end result is that no one knows what treatment was effective,” said Falzarano, who is from Winnipeg.

So in this study, he and colleagues infected kidney cells from green monkeys and rhesus macaques. Munster and other Rocky Mountain scientists recently published that macaques are an animal model for the virus.

They then treated the infected cells with ribavirin, interferon alpha 2b and the two in combination.

Neither drug was practical on its own. Ribavirin alone would need to be given in such a high dose it would be toxic, Falzarano explained. And it would be hard to get enough interferon to the infected cells to affect treatment.

Together, however, the drugs appeared to work.

“When we add both together, the dose you require of each falls basically into the level that you would achieve with a normal ribavirin dosing schedule, and a dose of interferon that you can readily achieve in a human,” said Falzarano, who also cautioned that more work needs to be done to see if this will help save people who become infected with the new virus.

The virus first came to the world’s attention last September, when scientists reported finding that a new coronavirus had infected and killed a man in Saudi Arabia. It was later determined that at least two people in a puzzling cluster of 11 unexplained illnesses in Jordan last April were also infected with the virus.

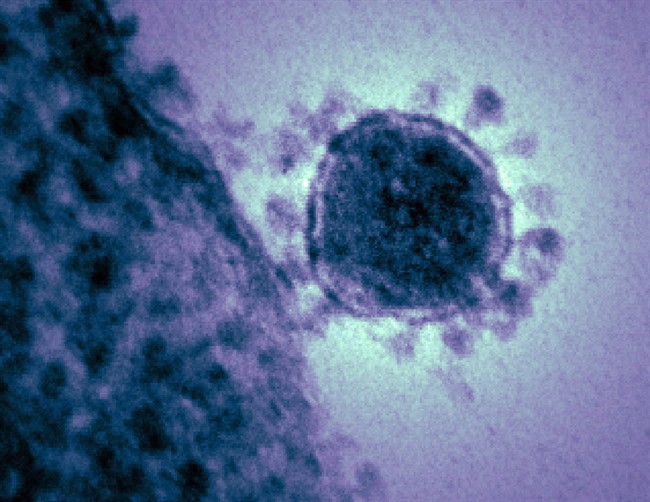

The novel coronavirus, which the World Health Organization currently calls NCoV, is in the same family as the SARS virus. Like SARS, it is capable of causing severe respiratory disease in people who catch it. Eleven of the 17 confirmed cases have succumb to their infections and to date few mild cases have been seen.

In addition to Jordan and Saudi Arabia — which has racked up the highest number of cases — infections have also been reported from Qatar, Britain and the United Arab Emirates. Britain’s three cases were in a cluster, triggered when a man returned sick to the U.K. after travelling to Pakistan and then Saudi Arabia. He went on to infect two members of his family.

Comments