Every morning, when Whistler resident Mark Edmondson walks to work, he takes the longer route through the forest.

This way he can visit the memorial garden and be with his son Owen Benjamin, who died five days after his birth in October 2014. He suffered from a loss of oxygen during an emergency delivery which caused severe, irreparable brain damage.

Edmondson and his wife said goodbye to their son under an oak tree on the grounds of BC Women’s Hospital on a rainy October night.

“We weren’t in control of his birth and what happened there,” he said. “But we could at least be in control of his death and make it peaceful.”

When they were ready, doctors took out Owen’s breathing tube. “And they all left, except for this one nurse who stood silently behind us, holding an umbrella over us, while she was getting drenched for however long it was,” said Edmondson.

They told Owen it was OK for him to go. But for Edmondson and his wife, Owen will always be a part of their lives.

“He might not be here physically but he’s still here in spirit,” he said.

“We make every effort to include him in what we’re doing. We still want to parent him.”

The dads who spoke to Global News after either having experienced infant loss or a stillbirth said that afterwards, most of their attention was focused on their wives and partners, and that’s to be expected.

But they also found that their grief was often not acknowledged in the same way, and sometimes not at all.

He said when a midwife came to check on the couple after Owen’s birth, she only talked to Robyn. “And the only thing she said to me was when she arrived and asked ‘is Robyn doing OK?'”

“For someone who’s trained in the profession, to kind of have that societal expectation as well, I’m sure some of it is nature, but I’m sure a lot of it is nurtured by this concept of the man being the strong pillow or model, kind of thing,” added Edmondson.

He said he understands the fact that the loss of the initial physical attachment is so much stronger for the mother.

“I was focused more on the loss of having someone to teach how to play football and to chase around in the garden and show wildlife to and that sort of stuff,” he said. “Which I realize is years away, but that’s how the loss hit me.”

Elizabeth Blake

Dave Shannon, whose daughter Elizabeth Blake Shannon died in utero due to a knot in her cord, said he knew he had to assume the role of being ‘The Strong One’ in order to keep life going. He and his wife Caitie also have two other children.

“One of the big things that stuck out for me was I sort of had to put my own grieving on hold,” he said. “Caitie obviously needed my support. She knew Elizabeth far more than I did. I only got some glimpses in some monitors and then I only got to hold her for a day.”

Shannon said he didn’t mind assuming that role to give his wife and his family time to grieve. But he knew he would need some time for himself and in the beginning, his grief manifested itself as anger.

“For the first month or so I was wound pretty tight,” he said. “I was pretty angry and I couldn’t express myself because it was a very odd time.”

“My anger was more about the fact that how dare they take my Elizabeth away from me. We went through all of that time and effort and money to have it just stripped away from us and that made me so angry. That made me more angry than anything else.”

Valley

Eric Hill’s daughter Valley was stillborn last June. She passed away in his wife’s womb a couple of days before she was born.

As a grieving father, he also struggled with how to support his wife and family and allow himself the time and space to mourn the loss of his daughter.

“I knew I had to be emotionally strong,” he said. “Yes, I held my ground for a bit, but I knew if I blacked out those emotions to be strong for my wife, I knew I would be losing out on those emotions.”

He said, from his experience, men feel like they have no one to talk to sometimes and may feel like they are left behind in their bereavement.

He approached his grief by talking about his daughter as much as possible, even though the pain of mentioning her name was sometimes overwhelming.

“Every day I wake up, I see her face on the wall,” he said. “Every day I go out to work, I always see her.”

“I keep living, breathing for her. And as long as my heart’s going, she’s going with me.”

It’s no secret that some men find it difficult to talk about their feelings and emotions, especially to other men.

“It would be a group of guys sharing their feelings and guys aren’t exactly known for that. We don’t naturally go around and have a big group discussion about our feelings.”

But all the fathers say talking about their children and being acknowledged in the fact that they lost a child helps them and others in the grieving process.

READ MORE: Stillbirth and infant loss: Your stories

Faith

Hung Nguyen’s wife had a stillborn daughter, Faith, in 2011.

He said they were lucky in the fact that they were able to spend four days with her in the hospital before they had to say goodbye.

Families and groups around B.C. are now raising money to get hospitals a cooling cot or a cuddle cot, which is a device that keeps the deceased baby cool, allowing the family to spend more time with the baby.

Nguyen said he and his family still mark Faith’s birthday every year and still talk about her as often as they can.

“I just talked about it a lot,” said Nguyen when Faith died. “I just found for myself the more I talked about it, the better I felt about it. Different times I’m up and down about it. It’s easier to deal with on certain days.”

“It never gets easy, but it’s a matter of talking to people and just educating people.”

Edmondson agreed, saying he has found that acknowledgement is one of the most powerful and important things someone can do in dealing with grieving parents.

He said the worst experience is seeing people who know what happened but do not even try to acknowledge it.

“We live in a small community obviously and we know a lot of people, and even people on our street just almost blank us,” he said.

“We feel it’s very selfish for someone to not be able to overcome their own fears when they can probably, at least partially, know what we’re going through and that it’s way worse than them just saying something or feeling bad.”

However, Edmondson knows that if the tables were turned, he and his wife would struggle to say the right thing to comfort someone in their deepest grief.

He said the support of people just willing to sit with them, or hug them, helped immensely. “They’ve helped us get to a point where we can do day-to-day things and survive,” he said.

Help raise money for a Cuddle Cot in a B.C. hospital.

Hill said he wants to see the government do more to help grieving families who are going through the loss of a child. He had to drop out of school when Valley died and even though they received financial help from their family, he knows many other families are not awarded the same opportunity.

“Some of us males aren’t always in the best financial position and it feels like you have to suck it up, go back to work, when we’re already fragile losing a child,” he said.

“I can tell you, no parent should go through the passing away of a child, it’s one of the biggest fears of anybody I think. Even passing away yourself is not as scary as losing a child.”

A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Health says there are care teams in hospitals throughout B.C. that are trained to support families through the loss of a child through stillbirth or infant loss.

“Health authorities provide access to social workers to provide comfort and support during this time. Families are also provided with information, including resources they can use.”

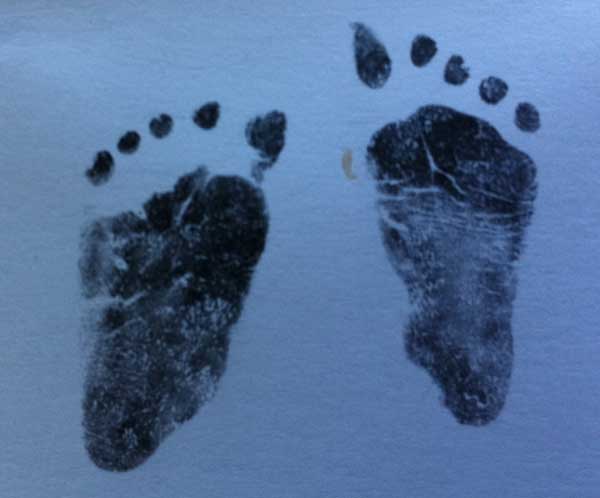

The hospitals also support the family by taking pictures and footprints so they can take home some memories of their child.

“Parents can also receive services and support through a family doctor, midwife, nurse practitioner, nurse or mental health professional,” said the ministry in a statement.

Through the Provincial Health Services Authority, parents can access services such as the Early Pregnancy Assessment Centre, the Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Clinic, and the B.C. Reproductive Mental Health Program.

While nothing can ever take away the pain of losing a child, these fathers agree that no one should be afraid to ask about their children or talk about them.

“I had to be strong, I had to be the one to go to the neighbours to explain to them what was going on,” said Shannon. “In a weird way I almost looked forward to doing it because it made me feel more pain so that I could kind of get a little closer to Caitie’s level of pain.”

“It was almost like a self-infliction so that we could somewhat get a little bit closer.”

“Also in a way, because I was reaching out, to neighbours and friends and family and stuff like that, I was able to heal a little bit faster as well because I was able to start having connections with people.”

“I could talk about her.”

Comments