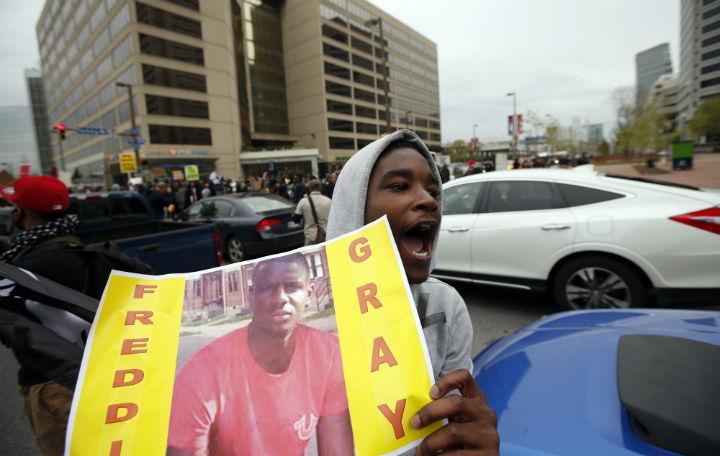

Anyone questioning what role poverty played in the life and death of Freddie Gray need only look to court documents to see how growing up in an impoverished part of Baltimore stacked the deck against him.

Raised in a very poor part of the city, the Sandtown-Winchester neighbourhood, Gray spent his early years being poisoned by the lead paint chipping away from the walls of his family’s rented home.

READ MORE: Baltimore police hand report on Freddie Gray death to state prosecutor

Gray, his twin sister Fredericka and older sister Carolina all had medical issues and behaviour problems (either attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or attention deficit disorder) as a result of high levels of lead in their blood at a very young age, the Washington Post reported.

Exposure to lead did not necessarily lead to the 25-year-old’s criminal history and thus his arrest on April 12, or to the subsequent spinal injury he’s believed to have sustained in police custody and his death a week later. But, it’s one more factor in a tragic life affected by poverty and crime.

READ MORE: Baltimore police van carrying Freddie Gray made an extra stop new video reveals

Gray’s family filed a lawsuit in Baltimore City Circuit Court in 2008 against the owner of the North Carey Street row house they rented for $300 a month between 1992 and 1996 — when Gray and his sister were between the ages of two and six. An out-of-court settlement was reached in 2010.

Even before moving into that house, Gray had lead in his blood. The twins were born two months early, on Aug. 16, 1989, and had to remain in hospital for months.

The following May, blood tests showed Gray had double the amount of lead in his blood than the Center for Disease Control now considers a “level of concern,” according to the Washington Post. He had 10 micrograms of lead per decilitre of his blood. The CDC’s “level of concern” is now 5 micrograms per decilitre, but it was previously 10 micrograms.

READ MORE: Baltimore mom who smacked rioting son speaks out

But by the time he was 22 months old, the amount of lead in his blood had more than tripled to 37 micrograms per decilitre.

“The fact that Mr. Gray had these high levels of lead in all likelihood affected his ability to think and to self-regulate, and profoundly affect his cognitive ability to process information,” Dan Levy, an assistant professor of pediatrics and Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, told the Post. “And the real tragedy of lead is that the damage it does is irreparable.” He told the publication many children lead similar lives to Gray’s — struggles in school and trouble with the law.

READ MORE: Why some Baltimore leaders say ‘thug’ is the wrong word to use

Lead paint was banned from being used in homes built from 1978 onwards, but the home Gray lived in for those four years was built well before that. The owner, Stanley Rockhind, has been named — and fined — in lead paint-related lawsuits. Rockhind reportedly owned around 1,000 homes in Baltimore. Maryland’s Department of Environment fined him $90,000 in 2001 and last November he was one of the defendants in a case that ended in a $1.4-million award for a woman “who claimed she suffered permanent brain damage and learning difficulties from exposure to flaking lead paint,” the Baltimore Sun reported.

READ MORE: Rallies held across the U.S. after death of Baltimore man

Some studies have suggested there is a link between removing lead paint from homes — and gasoline — in the 1970s and a drop in crime.

“Because of these actions, children born in the mid- to late-1970s grew up with less lead in their bodies than children born earlier. As a result, economists argue, kids born in the ’70s reached adulthood in the ’90s with healthier brains and less of a penchant for violence,” Lauren K. Wolf wrote for Chemical & Engineering News in February 2014.

Wolf’s article relied greatly on the research of economist Rick Nevin. In a 1999 paper, Nevin looked at how lead factored into the relationship between IQ and both crime and unwed pregnancy.

“During the years when gasoline lead was used extensively, children exposed to urban atmospheres and to interior lead paint in their homes had about six times higher daily lead intake than suburban children with minimal lead exposure,” Nevin wrote.

“Temporal trends in IQ, violent crime, and unwed pregnancy show a striking association with changes in blood lead levels and gasoline lead exposure for very young children,” Nevin explained in his conclusion. “Although crime and unwed pregnancy rates are obviously affected by a variety of factors, temporal trends in lead exposure appear to be a significant factor associated with subsequent trends in these undesirable social behaviors.”

“This is the toxic legacy of lead-based paint,” Ruth Ann Norton, who was a founding member of the Maryland Lead Poisoning Prevention Commission, told the Baltimore Sun. “They’re less likely to be able to hold a job. … They’re less equipped to be able to overcome the poverty and other circumstances that pull them down.”

Comments