WATCH: Experts warned a major quake in the mountainous country of Nepal was just a matter of time. But because of poverty and lax building codes, the country wasn’t prepared. Eric Sorensen walks us through the anatomy of a quake.

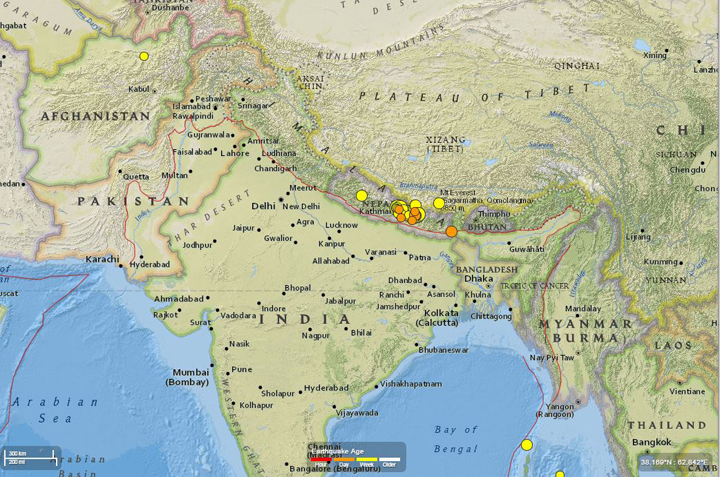

TORONTO – Following the devastating earthquake that is believed to have killed more than 4,000 people across Nepal and India, seismologists are aiming to better predict such earthquakes.

Though that part of the world doesn’t get rocked by many powerful earthquakes, it’s known to be an active region. And it all started hundreds of millions of years ago.

READ MORE: WATCH – Dramatic video shows Mount Everest avalanche following Nepal earthquake

Roughly 250 million years ago, Earth’s land was a giant supercontinent called Pangaea. About 200 million years ago, it began to break apart. These plates drifted until they eventually joined and formed the continents as we know them today. There are eight large plates and nine smaller plates.

The problem is, they’re still moving. And when that happens, we feel them as earthquakes — some major and some mere tremors.

India, one of the youngest continents on the planet, was one of last to break off during the continental drift. In 40 million years, it moved several thousand kilometres. While that may not seem like a lot, it is.

“The Himalaya reveal how strong the collision is, how active it is,” said Dan McNamara, a research geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey. “It’s the highest mountain range in the world. I believe the convergence rate between the two varies between 20 and 40 mm per year, which is pretty fast. ”

To compare, the San Andreas fault moves about 2 mm each year.

But it’s not just the speed of the continents that resulted in the Himalayas. It also has to do with what the plate is made of: as opposed to being comprised of hard minerals like basalt (found in areas like Hawaii, for example), the crust is made up of softer material like quartz that allows it to be thrust upward far easier.

So the movement of the Indian plate– subducting, or moving beneath the Eurasian plate — is what caused Saturday’s earthquake.

But seismologists don’t know a lot about the interaction of those particular plates.

“It’s a very unresolved, very poorly understood area,” McNamara said. “You’d think we’d know better by now, but this event is a good example of how little we know about the region. The closest seismic station to the event is 500 km away.”

WATCH: Earthquake in Nepal

The reasons for the lack of knowledge are many. For one, there is the political: until recently, China didn’t share its data with other countries. Then, there’s the fact that the region is fairly poor: Nepal doesn’t have its own monitoring network. And though India does, it doesn’t monitor north of their border.

Statistically speaking, a magnitude-8 earthquake is only expected to occur every 100 years or so in that part of the world. It hasn’t seen a major earthquake since 1935, when more than 10,000 people were killed.

McNamara said that teams are being dispatched to the area to set up temporary monitoring equipment.

“We can learn a lot from the aftershock sequence. We can use better recorded aftershocks to estimate the depths of the earthquakes better,” he said. “For example, we don’t know the depths very well. The uncertainty is very large.”

The uncertainty is so large, in fact, that it’s plus- or minus-15 kilometres.

And the rocking isn’t over for the region: the aftershocks could go on for six months to a year, he said.

What can be done to better predict an earthquake like this in the region? More monitoring and sharing of information. Though, of course, it’s not entirely simple: even if there had been swarms of earthquakes, it doesn’t necessarily indicate with certainty that a big one is on its way.

“It’s going to take a lot more time and a lot more observations of these sequences to figure out how to forecast,” McNamara said.

WATCH: Drone captures scale of devastation around Kathmandu

Comments