EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was updated to reflect the correct initial cost of the Tunnel Drive #2 micro-tunnelling work. It is $24,700,000, not $24,700,00.

There is a new and significant hurdle facing the massively over-budget and contentious Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project running through Alberta and British Columbia.

The Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc, a First Nation in the Interior of B.C., near Kamloops, is disputing a proposed change by Trans Mountain to the pipeline route through an area known as Pípsell.

The Nation, known by its acronym SSN, says the change in construction methodology and routing of the pipeline will severely jeopardize what it considers a “cultural keystone place.”

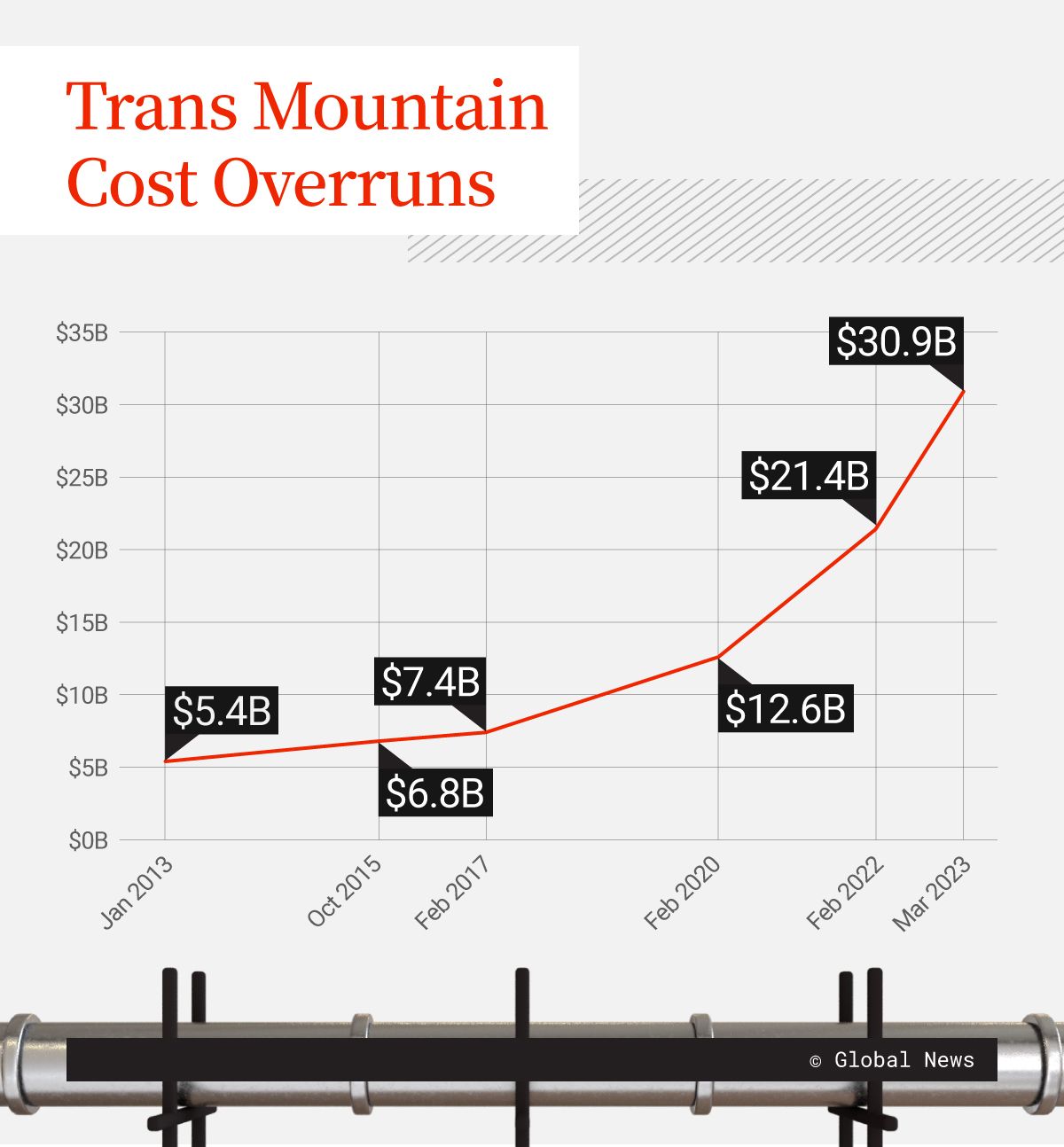

The pipeline project’s cost has already soared from an initial purchase price of $4.7 billion by the federal government in 2018, to a whopping $30.9 billion – and it is still not complete. This latest hurdle poses yet another potential cost overrun, and delay, for Trans Mountain, whose debt is backstopped by the federal government and could very well be borne by Canadian taxpayers.

Canada’s energy regulator has agreed to listen to SSN’s case against Trans Mountain’s 11th-hour change in plans. Those hearings will begin on Monday in Calgary. If the regulator rules against Trans Mountain, the pipeline giant may very well have to dig deep into its pocketbooks and find millions of dollars of extra cash to complete the line according to the construction method it had initially agreed to.

Changing the plans

In its negotiations with SSN, Trans Mountain had agreed to employ a technique known as ‘micro-tunneling’ to traverse Pípsell, which is also known as Jacko Lake. This method entails digging a shaft and meticulously pushing the pipeline under the lake in a process that would create the least amount of surface disruption and pose the smallest degree of risk along a four kilometre stretch of the Indigenous territory.

Instead, Trans Mountain is proposing to change the construction method – employing a less costly, yet more disruptive technique that SSN fears will pose undue risk to a sacred lake.

SSN insists Trans Mountain is changing its plans to cut overall costs on a project that has already gone six times over budget.

“These reasons are insufficient to demonstrate that Micro-Tunnelling in the Pípsell Area is no longer a viable method of construction.”

- Gardeners need to watch out for these 2 worms in Ontario. Here’s why

- Satellite built by N.B. students not responding a week after entering Earth’s orbit

- T. Rex an intelligent tool-user and culture-builder? Not so fast, says new U of A research

- Stuck in B.C. lagoon for weeks, killer whale calf is finally free

Indigenous monitoring group raises concerns

In a separate response to the energy regulator, an Indigenous advisory and monitoring group established by the federal government at the request of First Nations leaders, is similarly warning of irreparable damage should the construction plans at Jacko Lake be altered.

“There is no amount of money that Canada has, that can replace a site that’s sacred,” says Raymond Cardinal, the chair of Trans Mountain’s Indigenous Advisory and Monitoring Committee.

Pulling the plug on previously agreed-upon plans, he says, essentially renders the consultation process meaningless, and sets a terrible precedent.

“It shouldn’t be as easy as ‘well, we looked at it, and it’s going to cost money, so we’re going to do whatever we want to do.”

Trans Mountain says the original budget for completing the micro-tunneling project was forecast at $24,700,000. However, like many other aspects of the project that have gone significantly over budget, the cost of construction on a portion known as Tunnel Drive #2 has since risen to $58,900,000.

Documents reviewed by Global News indicate that 55 per cent of Trans Mountain’s latest cost overruns are attributable to what the company calls “engineering and plan maturity.”

The term ‘plan maturity’ is not widely used in the industry, but experts say it refers to finalizing construction and engineering plans. The fact that the company is changing its plans so far into construction is evidence of poor management and planning, according to at least three experts that Global News spoke with.

“What really concerns me is that if they’re still doing design and engineering planning at this stage, they haven’t known what they’re doing,” said Robyn Allan, an independent economist who has been monitoring the pipeline project for over a decade, in an interview over the summer with Global News.

That sentiment is similarly captured in a letter sent to the energy regulator by Cardinal.

From floor to ceiling

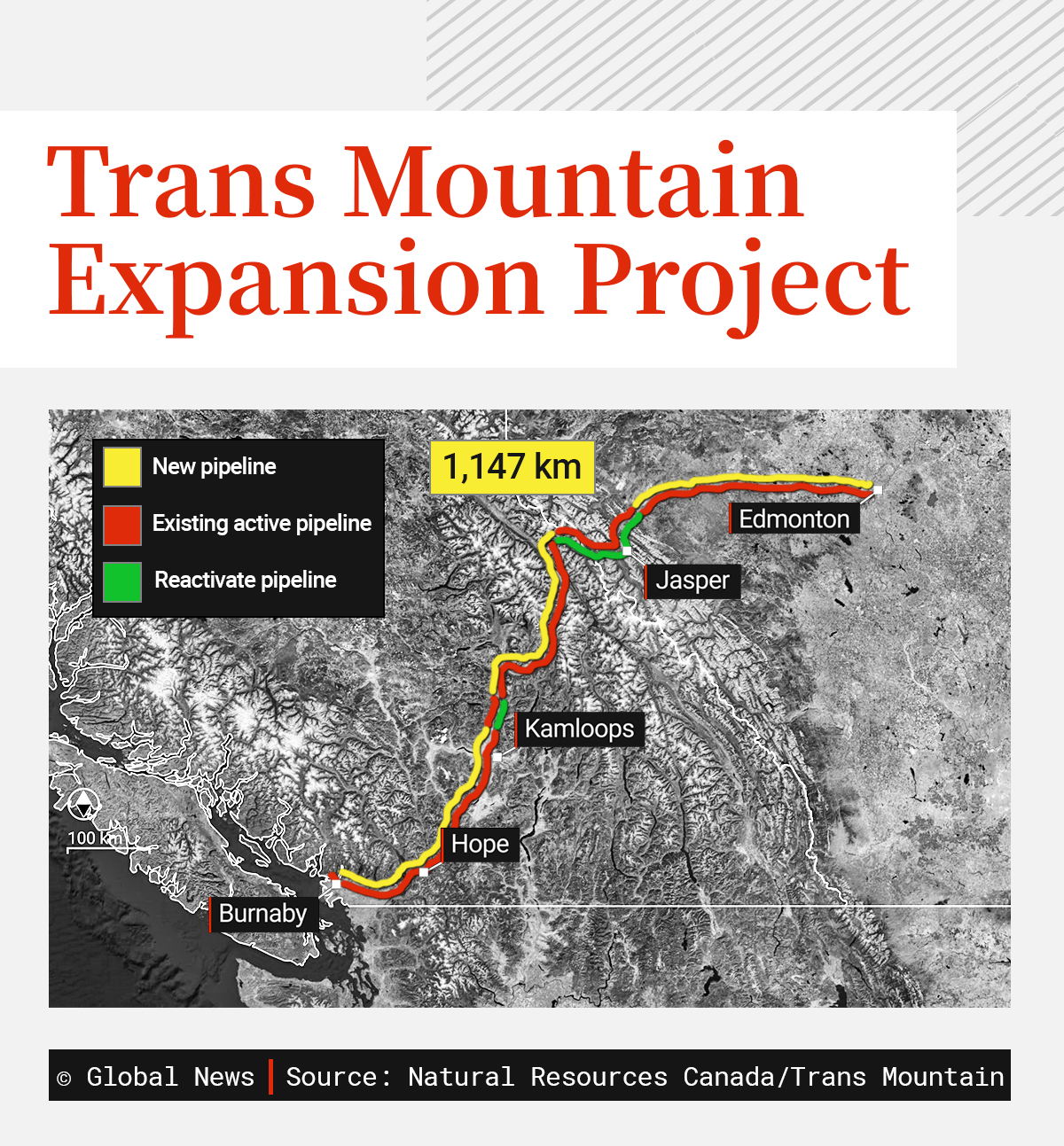

Trans Mountain fears that the delays in the Pípsell area will push back the anticipated in-service date of its new 1,147 kilometre pipeline, which twins an existing line to the B.C. coast, to the end of 2024. The company had hoped to send crude oil flowing through the line by early 2024. But that date, too, had already been pushed back as a result of several regulatory and construction hurdles.

Even at $30.9 billion, Trans Mountain says the pipeline will provide a significant cost advantage over a competing Enbridge line that is currently available to pipe Alberta crude to the U.S. Gulf Coast for export.

The goal of the new Trans Mountain line, which sends oil from Edmonton to a terminal in Burnaby, B.C., is to open up new markets in Asia to Canadian crude, via a shorter and more cost-efficient route. This is, say pipeline proponents, still a viable and worthwhile cause.

“Having another source of secure oil is a big deal,” Richard Masson, the chair of the World Petroleum Congress in Canada told Global News in July. But even he admits – a $16 to $20-billion cost overrun is a painful sticker shock for Canadians taxpayers to absorb.

“So it’s really cost way more than anybody would have dreamed at the beginning,” Masson added.

The roadblock involving SSN, says environmental lawyer Eugene Kung, serves as a warning to other Nations that have signed, or may sign future deals with Trans Mountain. It also reflects, he says, poor consideration of Indigenous rights by some large resource companies in Canada.

Too often, Kung says, companies are trying slide projects by Indigenous groups while only securing the bare minimum level of consent.

“The way to move forward is in fact to aim higher than the floor,” Kung says. “They need to do better than aiming for the bare legal minimum and hoping that that passes muster by the courts.”

Comments