By

Alley Wilson &

Farah Nasser

Global News

Published May 6, 2023

12 min read

Whether it’s a 360 immersive virtual experience to unlock memories, or social robots to assist with daily tasks, each evolution of immersive, virtual, and robotic technology being designed by researchers across the country is to help with an upcoming challenge Canada isn’t ready for: a surge in cases of dementia.

For Paul Lea it’s a matter of independence.

In 2010, Lea developed vascular dementia after having a series of strokes. He was only 57.

“For the first number of years, I didn’t move out of my apartment. I’d walk out in the street and I literally would run back in,” Lea said. “Life was hell. My daughter had to teach me how to live.”

She re-taught him how to cook, do laundry and even use his computer. But his daughter, Victoria, lives an hour away from his Toronto home, meaning Lea had to find a way to live with dementia in a safe but independent way.

And as technology advanced so too did Lea’s ability to do tasks on his own. For example, he uses a smart home speaker to help him turn on and off his lights. He also has a smart lock on his door that automatically closes in case he forgets.

“I rely on technology to live.”

He also uses different apps to achieve daily tasks and keep a schedule. MAXminder is specifically designed for older adults and those with mild cognitive impairment. It helps to schedule and remind Lea to eat, take his medications or to exercise.

There’s also the Life 360 app, which allows Victoria to monitor him while he’s outdoors going for a walk or running errands.

“And if I stop a certain place too long, then she’ll call me,” he added.

Lea is also an advisor to AGE-WELL, described as Canada’s technology and aging network. As an advisor, he offers suggestions on how to make apps, like MAXminder, helpful to older adults.

The AGE-WELL network includes hundreds of researchers across the country, committed to developing and refining tech to help Canadians age at home — and safely.

Lea’s experience is important for all Canadians because the majority of those living with dementia, about sixty-one per cent, live in a home setting and not in long-term care or nursing homes, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

The HomeLab at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute is a “home within a lab” where technology that helps older adults is tested.

Mihailidis also noted that people with dementia can still be active members of society.

“People with dementia, even quite severe cases, can continue to remain in their own homes and communities and can continue to participate in their daily lives,” Mihailidis told Global News’ The New Reality.

In the HomeLab, Mihailidis and the Toronto Rehab researchers have developed several technologies. Among them are apps, artificial intelligence, and even smart home systems. They also bring in seniors to interact with the tech and test the prototypes.

On the ceiling of the lab are sensors that are part of an automatic fall detection system.

“This is really to overcome the issue with current devices, which typically are pendants that the person needs to wear — push their button on their own, and then they’re connected to a live operator.”

However, Mihailidis says around 80 to 85 per cent of people who should be wearing pendants, aren’t.

Another reason why people don’t like wearing pendants is due to stigma, so Mihailidis hopes the automatic fall detection system will be a more practical solution for older adults with cognitive decline.

He believes the latest advancements in dementia-related tech can be available to everyone as consumer products in the next three to five years.

“At some point, because of the increasing numbers of older people, increasing prevalence of dementia, everyone is going to be touched by this disease in some way.”

When he first took on this role, it was about the research and advancements. Since then, his mother has been diagnosed with early cognitive impairment.

“I’ve gone from researcher to caregiver and that’s greatly has been informing my own work,” Mihailidis said. “It’s these personal experiences that really keep us going and I think personal experiences that drives, I would say, the majority of people within the AGE-WELL network.”

Aside from research and education, Mihailidis stresses that funding in this sector is a “big aspect.”

“We have gained so much momentum. Over the past 10, 15 years with the AGE-WELL network, and with others across Canada, now is not the time to take our foot off the gas. We need a strong national dementia strategy that includes technology in a very explicit way,” he said, citing that the current dementia strategy has not “been implemented very well across the country.”

He also believes technology needs to be a “far more dominant” factor in the blueprint.

“We need money put behind dementia care.”

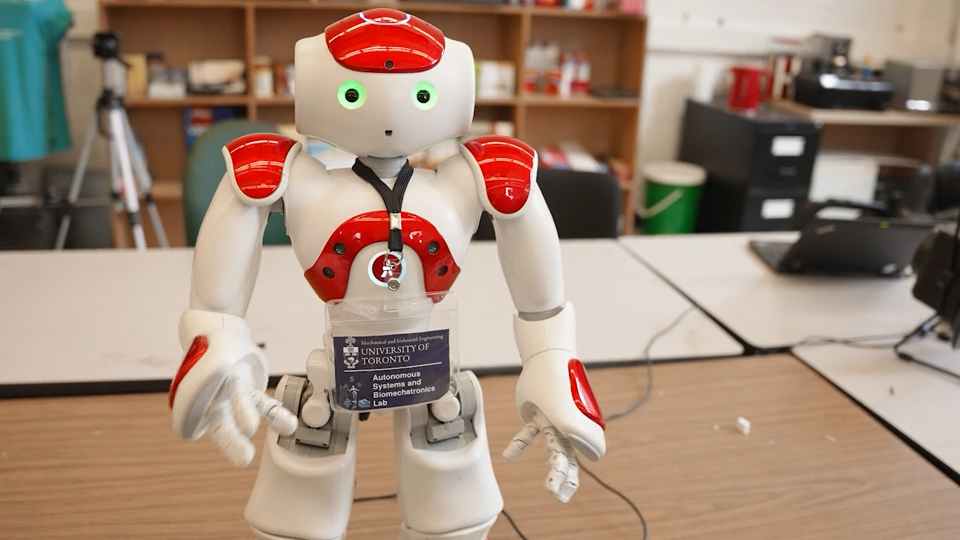

At the University of Toronto, social robots are being built and programmed to help older adults.

“It’s a really exciting time to be in robotics. There’s a lot of opportunities in terms of the development of robots to support people,” said Goldie Nejat, a professor in the department of mechanical and industrial engineering at the University of Toronto.

“We’re right now paving the way for this emerging technology.”

Nejat runs the robotics research lab. She is also the Canada research chair for robots for society.

“The idea is that we can design these robots to support cognitive interventions, social interventions, as well as helping people through the day.”

Robots don’t actually do the daily tasks but help to prompt and remind. Interaction is key as robots use a combination of verbal and nonverbal communication. Social robots can assist those living with dementia, whether at home or in a more traditional care facility.

Nejat, a world-renowned expert on social robots, and her team have conducted numerous user studies, “probably over 1,000 hours of interaction with older adults, those individuals living with cognitive impairments and dementia.”

“And we’ve seen high success rates, a 98 per cent engagement and compliance with the robots,” Nejat said.

Master’s students Fraser Robinson and Zinan Cen are working on Leia the robot, which is being designed to assist seniors with getting dressed. For example, Leia will prompt a user to put their arm in a sleeve of a shirt. Robinson explained why it was important for social robots to communicate the way people do, with facial expressions, gestures and speech.

“As you can see, (Leia) uses phrases like, ‘It would make me happy’ and also celebrates with the user when they have a success and when they reach the end of the activity. We’ve actually done previous research with other students and in other work that has shown that the emotional strategy is one of the best that works well with people because it’s able to connect with them in a very human way.”

There’s also Salt, the dancing robot to help with physical activity.

Nan Ling, a robotics student, says Salt is used to conduct dance sessions with older adults.

“We have a set of programmed movements and we match all the movements to each individual music,” Ling said.

There’s also Pepper, the health-screening robot that will ask visitors a series of questions to determine if the person is COVID-free and allowed to enter a facility.

“And if any of the screening questions were not passed correctly, then it would sound an audible alarm and ask you to go see reception. So there is always a person at the other end who will deal with any cases that require human attention,” said Cristina Getson, a PhD candidate in robotics in Nejat’s lab.

More research needs to be done when it comes to dementia and diversity, but Nejat said inclusion is at the forefront of her team’s work.

“We want to be able to have fair access to technology, no matter where you are in the country,” she said.

Meanwhile, in Hamilton, Ont. there’s an innovative retirement home built with technology and design as the focus.

Nafia Al-Mutawaly has a background in engineering, however, the former university professor’s path changed after his mother was diagnosed with dementia.

“Prior to this journey. I had no idea even what dementia means. And this is the truth,” Al-Mutawaly said. Through his journey, he hopes that with the help of others, he will be able to make a difference.

So he founded Ressam Gardens, a care home in his late mother’s honour.

“I hope that she would be proud,” he said. “If I can make one difference for a family then mission accomplished.”

While building the facility, Al-Mutawaly researched what would make life easier for the residents, such as lots of space to be together to socialize, and wander freely and safely. It is described as a retirement memory care community.

Ressam Gardens is also testing specialized lighting to help residents feel awake and active throughout the day, which will help with quality sleep at night. Residents will be able to change the temperature and intensity of the biodynamic lighting system as well. And if a resident wakes up in the middle of the night to get a drink of water, for example, Al-Mutawaly says a motion sensor in the baseboard of the room will activate lights.

“With this kind of low-intensity indirect lighting, we will be able to ensure the resident will not be disturbed when it comes to their sleep, and also to maintain the quality of their night,” he said.

Ressam Gardens also has specialized games to help with memory and movement, and the facility is working with the city of Hamilton to establish a Wi-Fi network in the 49-acre park across the street. This will allow residents to roam and be monitored safely.

Al-Mutawaly’s goal is to advance care for other families by determining what works and what doesn’t, and to provide the necessary information when it comes to dementia. Which is why he dedicated an office on-site for the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

“We don’t have the cause and we don’t have a cure. So what we are trying to do is to step into the unknown, and that is research,” Al-Mutawaly said.

“Hopefully, from these experiences, we will be able to put together the proper care that our residents need, and Canadians need.”

In Whitby, Ont., Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences offers specialized care for patients with dementia.

“Living with dementia is a complex situation where people lose their skill. They don’t lose it all at once, … but as the illness progresses, we know that there will be more and more complex needs that we hope technology will support,” said Dr. Amer Burhan, geriatric psychiatrist and physician-in-chief at Ontario Shores Centre.

The public teaching hospital teamed up with Ontario Tech University to innovate and test new approaches and tools to help caregivers and those living with dementia. One of these is reminiscence therapy.

The way it works is that residents will put on a VR headset and be virtually transported to a place where they’re most familiar, like their living room. And within the virtual living room are common features like a TV, photo album and music speaker.

“Family members can actually upload some personal pictures (so patients can) recollect memories from their past,” said Dr. Winnie Sun, an associate professor at Ontario Tech.

She said photos trigger the “memories they enjoy, the events or the places from the past that they really enjoy. It’s meaningful and relevant to them.”

Ron Beleno cared for his late father, Rey, who had Alzheimer’s for more than a decade. Now Beleno is an advocate for those with dementia, and he believes virtual reminiscence therapy can make a difference.

“The ability to kind of put on some kind of goggles or something so that he could actually feel and see, let’s say, what it’s like back in the Philippines,” Beleno said.

“You showed a photo of the Philippines, and you make him hear that as well. The sounds of the water and all that here, he’s going to start talking for about half an hour to an hour about the Philippines. And there’s a little bit of a cultural caregiving piece here.”

And for those who may not be comfortable with a headset they can always be immersed in the facility’s 360 virtual reality room.

Some common symptoms of dementia are agitation and aggression, so the team is using wearable devices that monitor things like body temperature and pulse rate, which could predict signs and symptoms which may precede an episode.

“It is quite distressing to the patient themselves as well as the caregivers,” said Elaina Niciforos, research coordinator at Ontario Shores.

“Being able to see what signs and symptoms are shown within five to 10 minutes before those agitation or aggression episodes is a really important indicator to helping them live their best life.”

And Dr. Burhan hopes that the work being done here will translate outside of the walls of the centre helping Canadians who are living with dementia and their caregivers.

“I think the trick is to be able to think about what is needed, co-design it with people who are involved, and then look at technological solutions that are suitable, implementable and scalable.”

See this and other original stories about our world on The New Reality airing Saturday nights on Global TV, and on globalnews.ca.

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.