When the government of Pierre Trudeau passed Canada’s Access to Information Act in 1983, it did so with the express purpose of creating what it thought would be an important new tool for governing democratically.

Indeed, the Act’s objective is set out in the first few paragraphs of the legislation: “to enhance the accountability and transparency of federal institutions in order to promote an open and democratic society and to enable public debate on the conduct of those institutions.”

But forty years later and despite promises made by Pierre’s son, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, to make this crucial tool work even better, the federal access-to-information system is in its worse shape ever according to a host of witnesses, including Canada’s Information Commissioner Caroline Maynard, that have spoken before a House of Commons committee studying the issue.

The biggest problem, according to those witnesses: Delays. Under the law, government departments are to provide requested records within 30 days of the request. They can take extra time when certain conditions exist.

According to Maynard, the government failed to meet its legislated timelines on more than 30 per cent of the 400,000 or so access-to-information (ATI) requests made in the last year. One Ottawa-based researcher, Michael Dagg, was told he would have to wait 80 years for records he asked for from Library and Archives Canada about some RCMP operations. That particular delay may be extreme, but delays stretching from months into years for relatively routine records requested are now increasingly common.

“Access delayed is access denied,” said Matthew Green, the NDP MP on the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy, and Ethics, which is in the midst of a study intended to recommend some fixes to the system. “In order to have parliamentary oversight, in order to have public trust, there needs to be quick and efficient access to information.”

Under the current iteration of the ATI Act, departments that fail to respond within legislated timelines do not face sanction. There are no fines and no penalties. Requesters cannot sue the government. The information commissioner has no power to force departments to respond. Each delayed request simply ends up as a data point in year-end reports on departmental performance. And, as Maynard told the House ethics committee, complaints to her office are already up 70 per cent this year.

“It comes down to a culture of secrecy,” said Michael Barrett, a Conservative MP who is also on the Ethics committee. “We’ve heard from witnesses, some of them with access-to-information requests spanning between five and nine years and some departments being worse than others. And then when they receive the access requests, they come back in some redacted form — blacked out with a lot of useful information missing. So it really creates a problem where people aren’t able to get the information they need in a timely way.”

Get daily National news

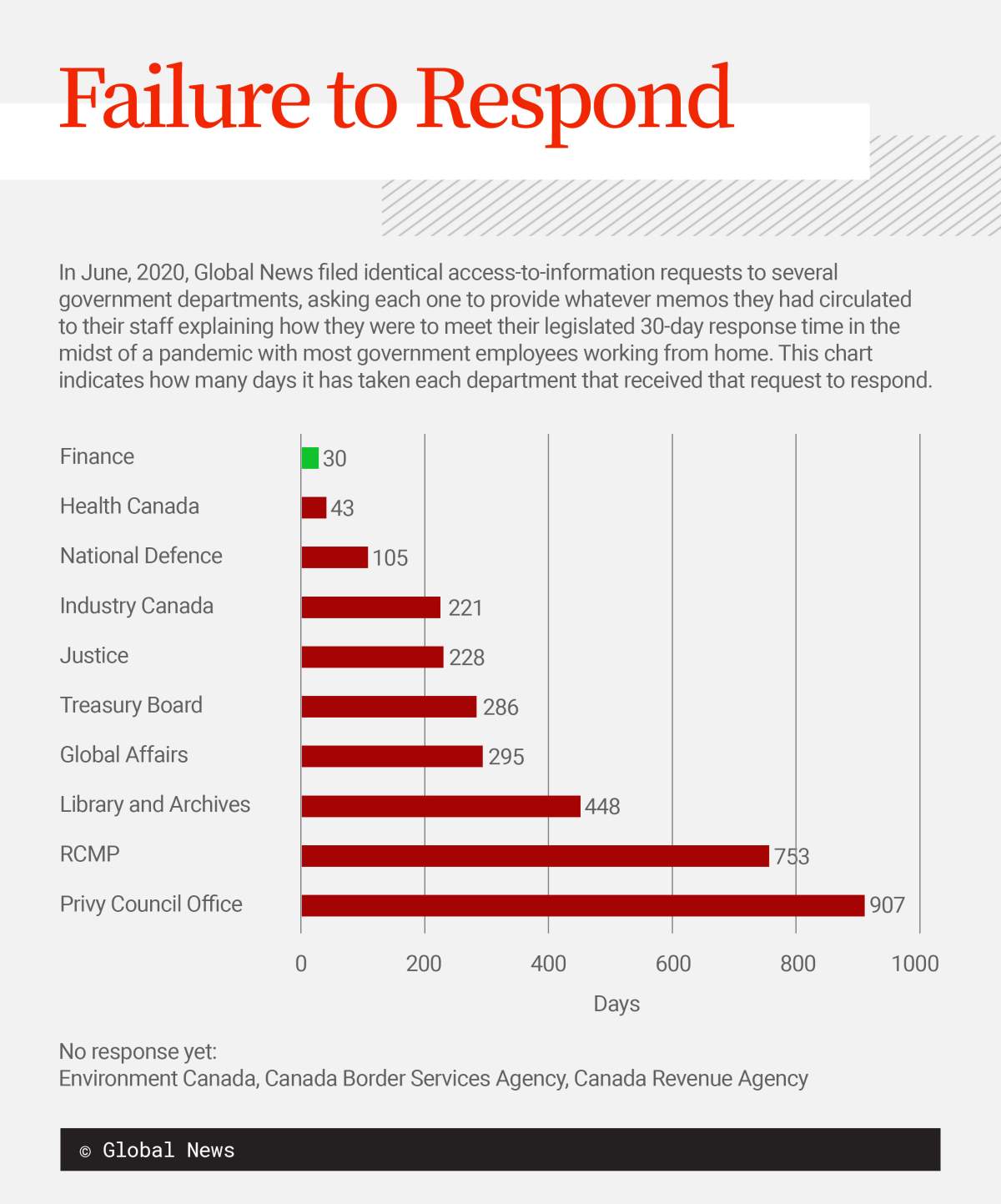

One series of access-to-information requests filed by Global News illustrates the uneven and poor performance of government departments in responding to requests in a timely fashion.

On March 16, 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic in full force, the federal government shuttered most of its offices and told most of its hundreds of thousands employees to work from home. And while it designated some employees as ‘essential’ it did not designate those working in access-to-information offices as ‘essential.’ As a result, the work in each department’s ATI shop began to grind to a halt as they could not access the secure computer networks in their offices needed to retrieve and process requested records. But as Information Commissioner Maynard would inform all departments during that COVID spring, even a pandemic cannot be used as legal justification for delaying the production of requested records.

And yet, on government websites and in correspondence from ATI analysts, the pandemic was cited time and time again as the reason records could not be produced under legislated timelines.

So, in June 2020, Global News filed identical access-to-information requests to more than a dozen large government departments. The requests were simple: Produce any memos or instructions circulated to department staff telling them how they were to do what Maynard had instructed them to do, which was meet their access-to-information obligations in the legislated 30-day timeline.

Only one department — the Department of Finance — responded to that Global News request in the 30-day window. Health Canada missed by a bit, responding in 43 days.

But the Department of National Defence provided the records in 105 days. Industry Canada took 221 days to respond. Global Affairs Canada took 295 days. The RCMP took 753 days.

And, last week, the Privy Council Office — the department that supports the work of the prime minister — finally provided the request records, 907 days after Global News asked for them. The records provided consisted of two e-mail messages and a PowerPoint presentation deck. Eleven pages in total. Not a word was blacked out, but it still took 907 days to process the relatively simple request.

Three departments — the Canada Border Services Agency, the Canada Revenue Agency, and Environment Canada — have yet to to respond to that June 2020 Global News ATI request.

“We’ve got a problem when we have journalists looking to report in real time on matters that are current in Canada. And it takes years or more to get information,” said Barrett. “It turns them into — as one witness said — into historians instead of journalists.”

Access-to-information requests from journalists make up a small minority of any year’s requests. More than 65 per cent of requests for information are made by everyday Canadians. Many more come from academics, business owners and not-for-profit organizations.

Maynard has provided the government and the ethics committee with a list of 18 recommendations to fix the access-to-information. She believes the system needs more resources and staff to process ATI requests as well as some rule changes. But, as she told the ethics committee when she testified before it in October, the access-to-information system will only improve when there is political will to improve it. In other words, the prime minister and his cabinet must make improvements a priority.

“Actions speak louder than words,” Maynard said. “Leaders must ensure that their institutions live up to their legislative obligations.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.