The passing of Queen Elizabeth II has put a renewed focus on the future of the Commonwealth, with some experts predicting more realms — particularly those in the Caribbean — will hasten to sever their ties with the monarchy.

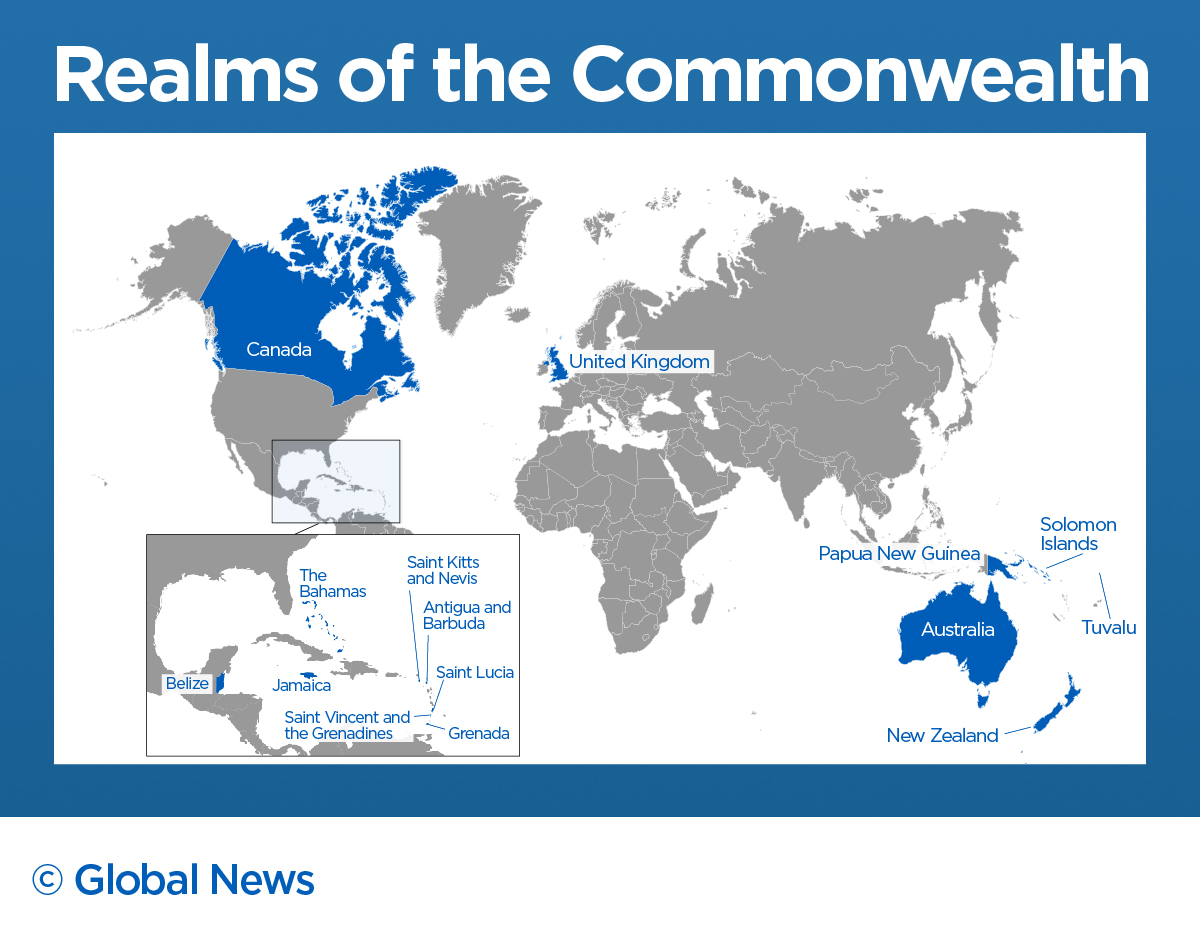

Although there are 56 members of the Commonwealth of Nations, only the United Kingdom and 14 other nations share the British monarch as their head of state, including Canada. That number has been dwindling since the organization was first formed in 1926, and experts say it will continue to do so regardless of who sits on the throne.

“I think (the queen’s death) may simplify the discussion, but it doesn’t change the fact that this has been an ongoing process of nations becoming more independent over time,” said Francine McKenzie, a professor of history at Western University in London, Ont.

Yet others say the ascension of King Charles III has lit a renewed fire for pro-republic movements in countries where the history of colonialism and slavery under British rule is still deeply felt.

In the Caribbean, apathy and even hostility toward the monarchy was evident when Prince William and Princess Catherine embarked on a much-criticized royal tour in honour of the queen’s Platinum Jubilee in March.

Protests greeted them along every stop as residents demanded an apology for the Crown’s role in slavery and colonialism. William did not meet those demands, though he did express “sorrow” for that history during the trip.

That tour came after Barbados became the most recent Commonwealth realm to officially become a republic, in a ceremony held last November that was attended by Charles himself.

“I think that will start the domino effect,” said Philip Murphy, a professor of British and Commonwealth history at the University of London.

“Lots of Caribbean states … have talked about becoming republics in the past.”

At a summit of Commonwealth leaders in Rwanda this past June, Charles appeared to accept that outcome, telling members that keeping or removing the monarchy as their head of state was up to each nation to decide while promising the Royal Family would not interfere.

McKenzie says member states who choose to sever ties with the monarchy can still benefit from remaining part of the Commonwealth, which has repeatedly committed to assisting smaller nations economically.

For now, a shift to republicanism remains a symbolic move that allows nations to further solidify their independence on the world stage.

Here’s what each Commonwealth realm has said about their future with the Crown, and whether the queen’s death has changed anything.

The Caribbean

Among the realms in the Caribbean, Jamaica has been the most vocal about its intentions to ditch the monarchy and become a republic.

Get daily National news

During William and Kate’s visit, Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness told the couple in front of reporters “we are moving on” and that Jamaica intends to be “an independent, developed, prosperous country.”

Despite reports earlier this year that Jamaica would be ready to officially sever its ties with monarchy by August — in time for the country’s 60th anniversary of independence from the British Empire — officials said this summer that it would take significantly longer.

Marlene Malahoo Forte, head of the country’s newly-created Ministry of Legal and Constitutional Affairs, told parliament in June that the process will most likely be completed by 2025, before the country’s next scheduled election. She confirmed, however, that the work was officially underway, which will culminate in a vote in parliament and a referendum.

Public sentiment appears to support such a move. A poll in August found 56 per cent of Jamaicans want the monarchy removed as head of state.

Elsewhere, Antigua and Barbuda’s Prime Minister Gaston Browne told ITV News at the Sept 10 accession ceremony for King Charles that his government will hold a referendum on becoming a republic within the next three years.

But other countries have been more vague, and have not set any official timelines for a transition or public vote.

Bahamian Prime Minister Philip Davis said the day after the queen’s death that a referendum for removing the monarchy as head of state is “always” on the table, reinforcing that it would be “our people who will have to decide.”

The government of Belize, which was the first stop on William and Kate’s Caribbean tour, created a new People’s Constitutional Commission just days after the couple departed in late March.

The office has begun consulting with citizens across the country on a planned “decolonization process,” which will consider whether Belize should become a republic. The consultations are expected to take roughly a year and will likely culminate in a referendum, government officials have said.

In July, St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves proposed a referendum on whether to keep the monarchy as head of state, which requires bipartisan support in parliament before citizens get to vote. The last referendum on the issue in 2009 saw just 43 per cent of voters support becoming a republic.

Australia, New Zealand and Oceania

There appears to be less urgency among Oceania countries to separate themselves from the monarchy — although the seeds for such a move are beginning to be planted.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese appointed the country’s first “assistant minister for the republic” shortly after his election in May, tasking Matt Thistlethwaite with studying a change to the country’s constitution and the possibility of a referendum on becoming a republic.

That referendum is not expected until a second term for Albanese’s government, if he were to win one.

Following the queen’s death, Albanese said it was “not the time” to consider a change to the country’s head of state.

Similarly, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern told reporters last week she had no intention to pursue a change under her government, although she added the country will likely become a republic “in my lifetime.”

Smaller countries in the region are mixed on the prospect.

Tuvalu, the smallest of the realms, launched a constitutional review this summer to consider whether to ditch the monarchy. Politicians argued during a debate that the queen represented “a colonial hangover” whose influence over the small collection of islands was “non-existent.”

Papua New Guinea, however, is standing firm. During Princess Anne’s visit to the country in April for the queen’s Platinum Jubilee, the country’s national events minister Justin Tkatchenko said the government was “embracing” its relationship with the monarchy in contrast to Caribbean nations.

What about Canada?

Although public support for the monarchy has been waning for years, Canada is unlikely to pursue republicanism anytime soon.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told Global News last weekend that the complicated process of removing the monarchy as head of state is likely a “nonstarter” amid pressing issues like inflation and the pursuit of reconciliation.

Abolishing the monarchy would require a feat of political maneuvering that has rarely been seen throughout the years, requiring unanimous agreement among the House of Commons, the Senate and all of the provincial legislatures.

Last week, Ipsos polling conducted exclusively for Global News just days after the death of the queen suggested nearly 60 per cent of Canadians want a referendum on the future of the monarchy.

That’s an increase from last year, when the sentiment stood at just over half of respondents.

At the same time, that poll suggested there is nearly equal support among those who favour both preserving or eliminating the ties to the monarchy.

— with files from Eric Sorensen, Amanda Connolly and Reuters

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.