In Abbotsford, B.C., efforts to prevent more flooding are happening non-stop — ahead of the next major storm on Tuesday.

Members of the Canadian Forces, alongside residents, are building dikes, drainage channels, and sandbagging with force. Over the weekend, B.C. got several more millimetres of rain, with more on the way.

The catastrophe in B.C. is accelerating a rethink in the way cities are planned and designed — with planners and engineers turning to nature for answers.

Typically, cities are designed to repel water: Rain falls on hard surfaces like concrete and asphalt, and gets channelled into drains and sewers. When that rain falls too fast, those drains become overloaded, inundating communities.

Instead, planners need to be thinking about how to absorb water. Enter the ‘sponge city.’

Build it like a sponge?

Concrete. Steel. Brick. These are the materials usually associated with strength in urban construction. But a sponge?

Turns out, a ‘sponge city’ can be incredibly resilient as well.

“Cities are areas (where) a lot of the natural surfaces have been covered with concrete … and (that) doesn’t allow water, including rainwater, to go where it naturally would, which is below the ground,” says Usman Khan, an assistant professor of civil engineering at York University in Toronto.

With even a little bit of excess rain, communities can quickly get messy as stormwater backs up drains, floods basements, and sometimes even allows sewage to seep in.

Using the sponge design, cities can store huge volumes of water — much like a sponge would — with forms of ‘natural’ infrastructure such as wetlands, green roofs and vegetated irrigation ditches known as bioswales.

This way, Khan says, “you reduce some of the risk of floods in urban areas.”

- TD Bank moves to seize home of Russian-Canadian jailed for smuggling tech to Kremlin

- ‘Alarming trend’ of more international students claiming asylum: minister

- After controversial directive, Quebec now says anglophones have right to English health services

- Why B.C. election could serve as a ‘trial run’ for next federal campaign

The technique also allows planners to “reintroduce nature into cities, and I think that’s a positive thing.”

But designing sponge cities requires a complete rethink in urban planning, and it’s already starting to happen.

Soaking up… the rain

Though China can’t take credit for inventing the concept, nowhere is the idea of sponge cities being deployed with as much panache as in that country. Its major cities are regularly subjected to flooding. The breakneck speed at which urban centres there have grown into mazes of concrete and steel has not helped them deal with all that excess water.

So China is turning to what President Xi Jinping calls an “ecological civilization” to manage floods. In 2013, Beijing announced a pilot project to implement the sponge design in 16 cities across the country, with a view on eventually rolling out the strategy nationwide.

In the city of southwestern megacity of Chongqing — population 16 million — there used to be nothing more than a concrete barrier separating the Fu River from the rest of the city. That barrier has now been replaced by a 99-hectare wetland park that acts as a giant sponge protecting people from water when the rains inevitably come.

Get daily National news

Other cities in China are following suit with sponge-like designs of their own.

But even in China, where ‘sponges’ are the size of football fields, there are questions about whether the strategy can prevent the worst floods. In the city of Zhengzhou, sponge design was no match for what was described as a “once-in-a-millennium storm” that killed 300 people.

“The sponge-city concept,” says University of Calgary civil engineer Jianxun He, “is more applicable for more frequent, small (rain) events, not for that very extreme event.”

This design, she insists, would only have a “very minor” impact in terms of mitigating a massive flood event, for instance, when huge amounts of water swell rivers from upstream runoff.

It cannot “100 per cent substitute or replace the existing stormwater drainage system.” But, she concedes, the sponge system can reduce localized runoff – and should be seen as one tool in the overall effort for cities to become more climate resilient.

And that’s precisely the point.

The sponge city concept, says Dafang Fu, a civil engineer and authority on their implementation across China, is not simply about “one technology” or one method applied here and there. Instead, he says the concept is really about ushering in a different “way of thinking” — one that integrates technology with urban design, along with a growing awareness by citizens of the need for climate resilience.

Shifting the mindset

“We really do need to shift fundamentally away from auto-centric paved surfaces that are associated with urban development, and much more toward living green infrastructures to which we connect as people,” says Nina-Marie Lister, who runs the Ecological Design Lab at Ryerson University.

“Better connections to wildlife, to park spaces, to trees, and to all the benefits of nature are … important for our mental well-being as much as they are for our physical well-being.”

Her own garden in the city is a hive of biodiversity, a far cry from the conventional format of a manicured lawn with trimmed hedges or a fence.

City planners are listening and adapting, and in some cases, spending significant sums of money to reintroduce nature into the cityscape.

Toronto’s Don Valley is an example of the sponge effect at work. It’s a big reason why resident Floyd Ruskin wants to see the valley protected from further development — to act as a natural barrier for floodwater.

The Brooklyn native moved north over 40 years ago, but at first he never really gave much thought to the pristine river valley and its water-absorbing ravines, ponds and green spaces. Now, he says, “I could take you to places (where) you wouldn’t know that you’re in the middle of Canada’s largest city.”

The notion of treating urban waterways like sewers, or simply paving them over, is changing. In the late 1960s, it got so bad for the Don River, Toronto residents even held a funeral for it.

These days, urban rivers, valleys and ravines are celebrated for the role they play in soaking up intense rains fuelled by climate change — literally for their sponge-like effect.

Along Toronto’s eastern waterfront, a billion-dollar infrastructure project is re-naturalizing the mouth of the Don River, restoring how it naturally opened up into Lake Ontario prior to the city’s rapid industrialization. The Port Lands transformation aims to mitigate the threat of flooding while creating new green spaces and an entire new community at the city’s doorstep.

Similarly, Corktown Common Park, a bit farther upstream, is built on former industrial land and engineered with the water-absorbing sponge effect in mind.

This is a complete role reversal for areas around the Lower Don River, a stone’s throw from Toronto’s downtown core. Green spaces built around the river soak up rainwater as well as runoff should the river overflow its banks, protecting city streets, and homes, in the process.

“Lately, we’ve come to recognize that an investment in the living world is also a kind of infrastructure,” Lister says. “So anything from green roofs, to living walls, to wildlife overpasses, parks even, might be considered ‘green infrastructure’ or ‘ecological infrastructure.’

“Not only is it time for a sea change,” she says, “but it’s also time for a deep reflection on how we design our cities.”

Canadian cities leading the way

Just about 100 kilometres down Highway 401, the city of Kitchener, Ont., has long been a leader in encouraging sponge-like resilience.

Twelve years ago, it came up with a stormwater utility bylaw, charging residents a fee that goes up with the amount of impervious area, such as a driveway, on a homeowner’s property. The more a resident reduces the amount of water flowing off their property, the less they pay.

“There are many more cities following suit now with this approach,” says Nick Gollan, Kitchener’s stormwater utilities manager. “And I think it’s an acknowledgment that climate change is happening.”

He says residents had questions when charges first started appearing on their utility bills. But then the city implemented a credit system to further incentivize homeowners who installed rainwater infrastructure on their property.

That’s when change really started to happen.

“I remember personally visiting some properties,” Gollan recalls. “(Residents) really wanted to showcase the things that they were doing.”

Building ‘with’ nature

Drawing on the benefits of nature has long been a part of Julia Pepler’s life. She grew up on the Toronto Islands which, like the Don Valley, are a natural treasure in the middle of the big city.

“It feels good to be by the water,” she says.

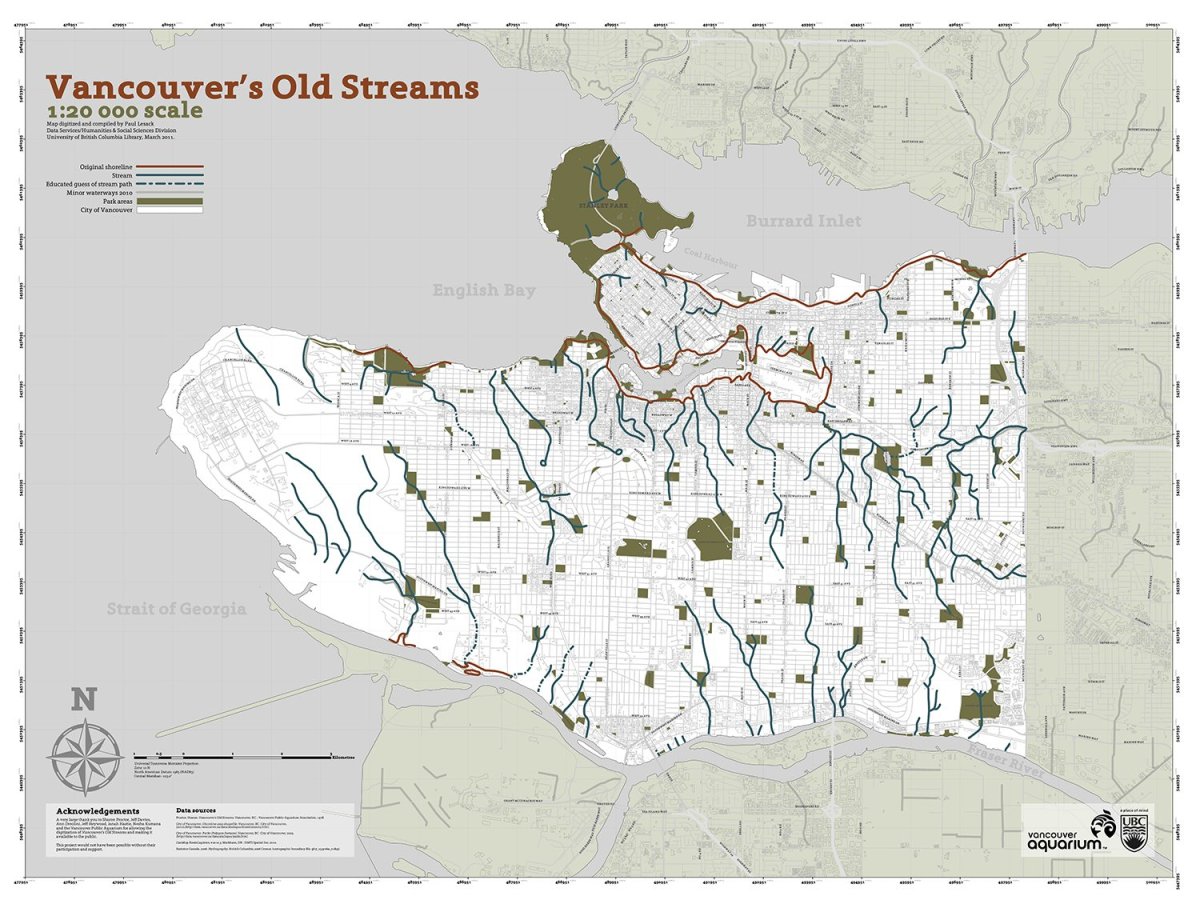

Two years ago, Pepler was cycling in Vancouver and came upon a strange noise next to a manhole cover. She stopped to take a look — rather, a listen — and discovered a rushing stream buried under the cover.

She did some research and discovered how that single stream is actually part of an extensive network of rivers and streams in Vancouver that has long been paved over.

“It’s so easy to forget that where we live … there was once abundant nature,” Pepler says.

These underground wonders are a reminder that water is meant to flow naturally into the ground, feeding rivers and streams that once used to be visible, and audible.

“It feels so important to me that people connect with nature and see nature because then they want to protect it,” Pepler says.

Bit by bit, the design philosophy is changing, with a recognition that “taming nature, paving it over,” was never the right approach, says Lister, of the Ecological Design Lab at Ryerson.

“(That approach) has brought us to the precipice of disaster.”

Toronto resident Ruskin thinks of it slightly differently. His own city has an extensive network of lost rivers that could act as natural irrigation channels for sponge-like design.

But it means protecting them, and in some cases, even daylighting them.

When you disturb a natural setting like the Don Valley, he says, “you have to wait 35 to 40 years for the wildlife to come back.”

“You can’t replace the environment.”

Comments