The first U.S. children under the age of 12 were vaccinated against COVID-19 on Wednesday, following approval of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 5-11 Tuesday evening.

And some Canadian parents don’t want to wait for authorities here to make up their minds.

University of Ottawa professor Amir Attaran, a dual Canada-U.S. citizen, said he plans to take his kids south of the border to get their shots.

“What Canadians are looking at here is, if they’re lucky, a one-dose Christmas for their children, more likely a zero-dose Christmas, while American children will have two doses and be fully protected,” he said.

“That’s a safe Christmas for Americans and an unsafe one for Canadians.”

Others are eagerly waiting to hear what Health Canada says. “I’ll definitely be vaccinating my kids,” Stefanie Ventura, a mother from Montreal, told Global News.

She especially wants her seven-year-old son, Daniel, who has epilepsy and lives with autism, to get the shot. “If he were to catch COVID it would be more detrimental for his health than to get the vaccine and protect him,” she said.

She’s excited for the chance to vaccinate her kids, she said, but she also believes it’s important that the government makes sure that the vaccine is safe and the rollout is done smoothly.

“As long as Health Canada approves it and it’s approved by the doctors and the panel, then I believe that it would be safe for our children,” she said.

“Parents are sitting on the edge of their seats, and I can say this as a parent myself to a young child at home, we are anxiously waiting to vaccinate our children, to protect our children,” said Sabina Vohra-Miller, the founder of Unambiguous Science, an organization dedicated to providing scientific information to the public.

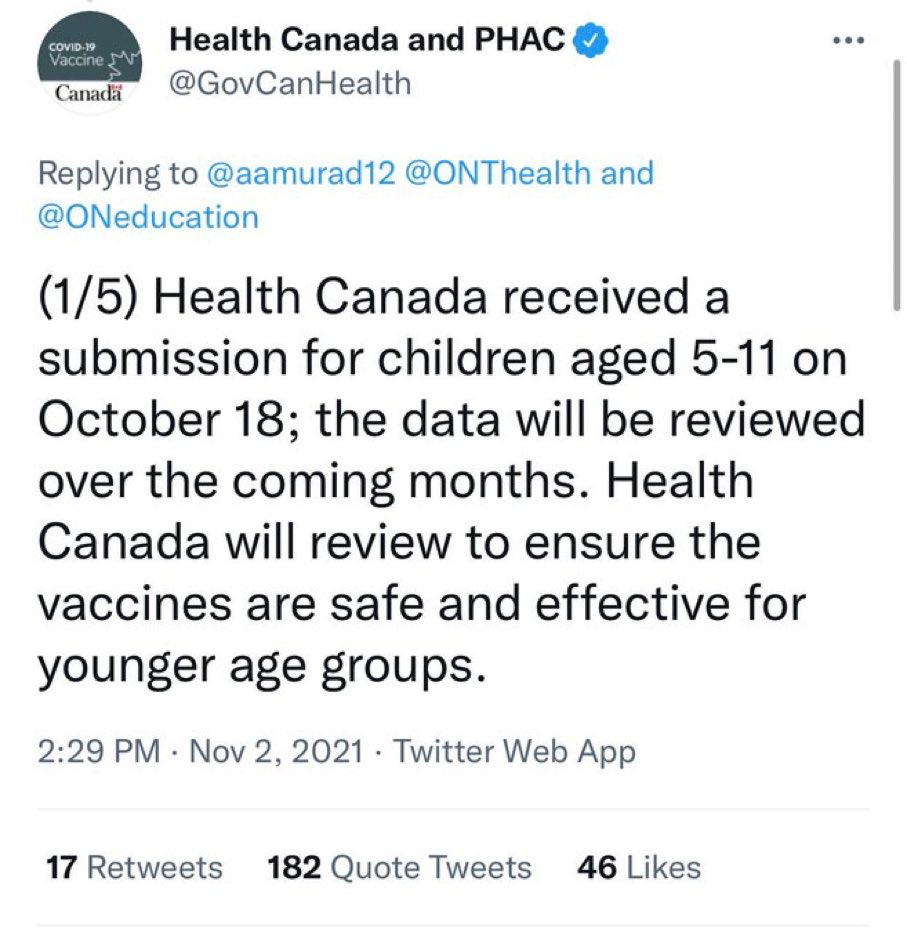

That eagerness has parents hanging on Health Canada’s every word — which caused a problem Tuesday evening as the department posted a message to Twitter.

“Health Canada received a submission for children aged 5-11 on October 18; the data will be reviewed over the coming months,” the department wrote.

Canadian parents were incensed at what seemed to be an unusually long timeline. “And now I am full of despair,” one wrote. “Reading this chill ‘coming months’ tweet and then getting another 4 notices about exposures at my kids school…” wrote another.

Vohra-Miller estimates she received more than 100 “frantic” messages from parents regarding the tweet, which was later deleted by Health Canada.

Get weekly health news

The regulator clarified Wednesday that the timeline was “weeks” not “months” — in line with previous statements from the department.

If Canada’s approval system was more transparent, this confusion could have been avoided, Vohra-Miller said.

“The issue really here is that in the U.S., the process for approval is extremely open and transparent. We have a good idea of what the discussions and deliberations are going to look like, what the dates are that we should look out for,” she said.

In Canada, the process is “tight-lipped,” leaving people scrambling for hints, she said. “So minor tweaks like this with a potentially minor typo can end up causing a lot more downstream chaos than necessary.”

Risks to children

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, nearly 21 per cent of COVID-19 cases in Canada so far have been in people under the age of 19. More than 1,700 people under 19 have been hospitalized due to COVID-19 over the course of the pandemic, and 17 have died.

“Thankfully the risk of hospitalization is considerably lower than it is for adults and especially the elderly,” said Dr. Jesse Papenburg, a paediatric infectious disease specialist and medical microbiologist at the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“But nonetheless, there have been hundreds of hospitalizations of children across Canada for COVID, either for acute COVID or for the post-infectious inflammatory syndrome that you see about four to six weeks after a rather benign COVID infection.”

Not everyone is so certain. Kelly Turpin, a mother of three from Montreal who isn’t vaccinated herself, said she doesn’t plan to vaccinate her children. The vaccine is too new, she said, and she doesn’t think children usually get sick enough from COVID-19 to justify the shot.

“I’m going with my instinct in saying that I’m not going to get them vaccinated,” she said, adding that she might reconsider if proof-of-vaccine rules shut her kids out of social activities for being unvaccinated.

There’s a lot of misinformation about side effects from the COVID-19 vaccine, said Dr. Anna Banerji, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto’s school of public health.

“A lot of what they’re saying is not true. So it is not linked to cancer. There’s no biological basis for that. It’s not linked to infertility. It’s not linked to changes in our DNA that’s going to have these long-term consequences,” she said.

In its statement recommending Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for children aged five to 11, the CDC wrote, “In clinical trials, vaccine side effects were mild, self-limiting, and similar to those seen in adults and with other vaccines recommended for children. The most common side effect was a sore arm.”

Banerji said it’s also important that kids get vaccinated to protect their family members and community.

“It’s to protect that child, but also to protect the community around the child. So the classmates, teachers, custodians, etc.,” she said. “So if a child doesn’t get vaccinated, maybe there’s not a huge impact on that child, but there may be impacts on a classmate’s grandfather who ends up in the hospital or dies.”

Banerji hopes to see Canadian approval of the vaccine for kids soon, saying the longer the government waits, the more kids will contract COVID-19.

“The five-to-11-year-olds are the largest population of people that get together in congregate settings,” she said. “And so once we get those kids vaccinated, then we’re going to have a lot more ability to deal with this pandemic and move past it eventually.”

-with files from Global News’ Jamie Mauracher

Comments