Prime Minister Justin Trudeau‘s new government is set to impose higher taxes on Canadians, which will help fund some campaign promises but are not broad enough to also start paying down the country’s record levels of debt, leaving Canada vulnerable to the next economic crisis, analysts say.

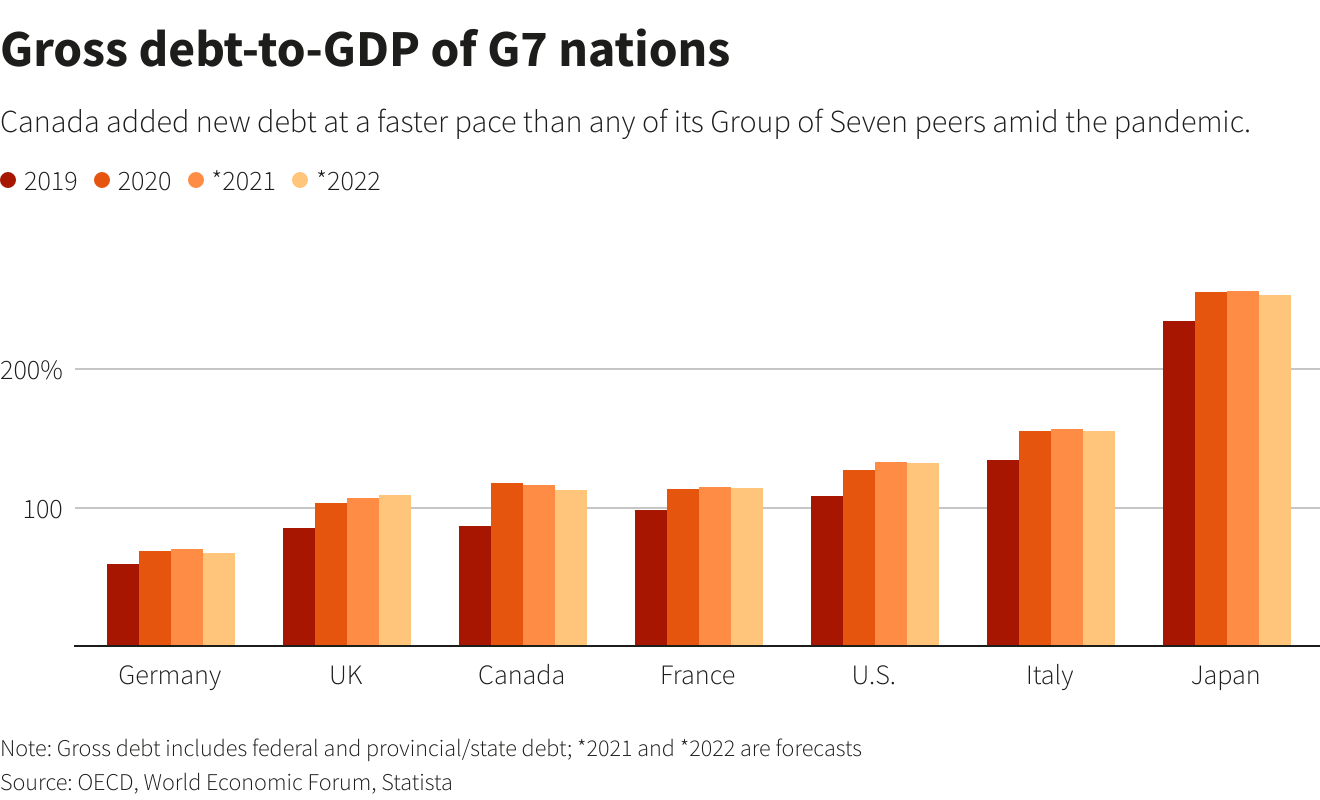

This could be a risky strategy for the country, which piled on new debt at a faster pace than any of its Group of Seven peers during the pandemic. The high level of indebtedness could limit Canada’s ability to manage long-term challenges that require massive government funding, like transitioning from a fossil fuel-reliant economy to a green one.

A far higher debt-to-GDP ratio post-pandemic means Canada has far less wiggle room to respond to the next crisis, be it economic, trade, climate or health-related, analysts say.

Essentially, Canada’s large debt burden “does not leave significant fiscal space to offset major new shocks,” said Kelli Bissett-Tom, director of Americas sovereign ratings at rating agency Fitch Ratings.

Fitch has already stripped Canada of a triple-A credit rating, but S&P Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service still give Canadian debt the highest rating.

Ahead of their re-election last month, Canada’s Liberals pledged C$78 billion ($63.1 billion) in new spending over five years, about 4% of gross domestic product, partially offset by C$25.5 billion in new tax revenues over the same period, mostly targeting tax evasion, wealthy individuals, big banks and insurers.

The idea is to tap those who best weathered the pandemic to pay for new spending on everything from mental healthcare to school lunch programs. But those taxes won’t help pay down Canada’s record C$1 trillion national debt, nor will they be sufficient to balance the budget.

This becomes risky because at some point the cost of carrying that debt will rise, and a future government may need to cut services or raise taxes further to address that burden, some economists warn.

“Nothing related to the cost of the pandemic…will be repaid by the current generation. And that’s very bold and risky,” said Don Drummond, the Stauffer-Dunning fellow at Queen’s University.

Tax the rich

Canada is not unique in looking to tax the wealthy to pay for COVID-19-era spending. But countries like the United Kingdom are making an effort to start paying down debt as part of their new tax plans, and Western European nations are signaling public debt levels won’t rise forever.

Get daily National news

Canada’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio jumped 36% last year to 118% amid massive government transfers of aid to individuals and businesses, by far the largest increase of the G7 group of wealthy nations.

That ratio, which includes all provincial and federal government debt, is set to drop to 113% by 2022, based on projections for economic growth rather than debt repayment.

Reducing Canada’s debt as a share of the economy over time brings in some sort of fiscal discipline, but that fiscal “anchor is destined to break during challenging times,” economists at BMO Capital Markets said in a post-election note.

Trudeau’s Liberals failed to score a majority in the Sept. 20 election and continue to be dependent on the left-leaning New Democrats (NDP) to pass legislation. That party could pressure the Liberals into more spending in exchange for their support.

The Liberals have pledged to increase the corporate tax rate for big banks and insurers, as well as introduce an extra payment by those same businesses to help pay for the economic recovery. The government also plans to impose a minimum tax rule for top earners.

Trudeau’s Liberals will need support from at least one other party to pass any new legislation, like changes to tax laws. The NDP favors tax increases on big business and the very rich.

“We had a lot of fiscal space, a lot. And we used a lot of it on the pandemic,” Dominique Lapointe, senior economist at Laurentian Bank, said, referring to the government’s record stimulus to support the economy.

“People are now worried because we used that fiscal space and we’re still continuing to introduce new measures.”

Comments