Red-hot lava gushing from the Cumbre Vieja volcano continues to wreak havoc on the Spanish island of La Palma, having destroyed buildings and forced mass evacuations.

The La Palma volcanic eruption that began on Sept. 19 is one of more than 50 around the world that are marked as “continuing” as of Oct. 12, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program (GVP).

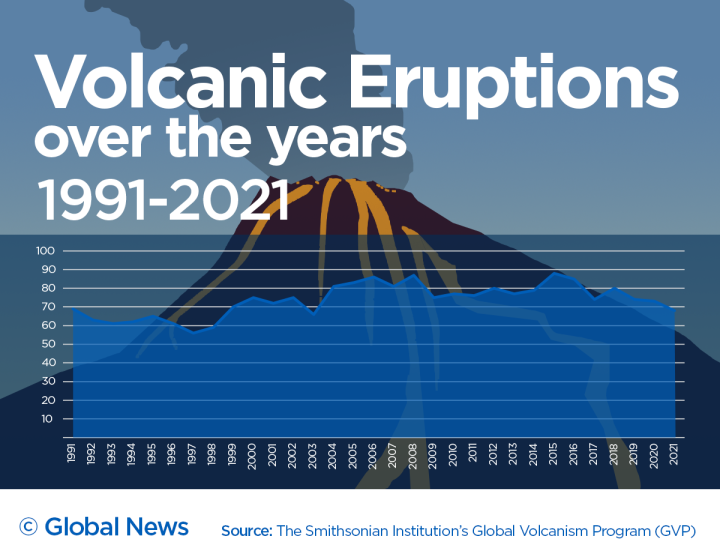

This year, 68 eruptions in 29 countries have been reported, compared to 73 in 2020 and 74 the year before.

Volcanoes have been erupting across the globe for thousands of years, with many remaining continuously active for decades.

Despite spectacular images and videos of eruptions becoming more common in recent years, volcanologists say there is no reason to suggest that volcanic activity has increased worldwide.

“There’s no evidence that the number or the scale or the size of volcanic eruptions on Earth is changing at all,” said Paul Ashwell, an assistant professor of earth sciences at the University of Toronto Mississauga.

“The pattern seems to be fairly steady.”

What causes volcanoes to erupt?

Volcanoes erupt when magma formed from melted rocks beneath the surface of the Earth rises up through cracks in the Earth’s crust.

Since the semi-molten or molten magma is lighter or more buoyant than its surroundings, that causes it to rise. The eruptions are also partly driven by pressure from dissolved gas contained in the liquid magma.

Volcanic eruptions typically occur in three types of regions: mid-oceanic ridges, subduction zones and hot spots.

The movement of tectonic plates — segments that make up the Earth’s crust — made possible by heat from the Earth’s interior is what drives the volcanic activity in these regions.

“Magma is produced in certain circumstances where the tectonic plates are moving apart or towards each other,” explained Ashwell.

How long can volcanic eruptions last?

The La Palma volcanic eruption has now entered its fourth week.

Eruptions can last anywhere from less than a minute to hundreds of thousands of years, said Johan Gilchrist, a researcher in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia.

According to the Smithsonian’s GVP, there were 101 confirmed eruptions dating back to 1750 that lasted at least 60 months.

Get daily National news

An eruption marked as “continuing”, however, does not mean continuous daily activity, but rather intermittent events without a break of at least three months.

This is different than an active volcano, which is either erupting or has the potential to erupt in the future. A dormant volcano has not erupted in a long time but is expected to erupt again.

“Generally, each volcano has its own signature behaviour,” said Melanie Kelman, a volcanologist at Natural Resources Canada.

Depending on the type of volcano, there is a “huge variability” on how it can behave and the frequency of its eruption, she said.

The range of behaviors include some that are continuously active erupting over and over again for decades, others that are brief and then shut down for a long period of time, as well as long-lived, low-level eruptions.

Canada’s volcanoes

Canada has at least 28 potentially active volcanoes in British Columbia and Yukon, according to Kelman.

But the country hasn’t seen any eruptions in almost 150 years, with the last one taking place at Lava Fork in northwestern B.C.

The most recent significant explosive eruption was at Mount Meager 2,350 years ago. The ash layer from that eruption can still be found as far away as Alberta, according to Volcanoes Canada.

Mount Garibaldi is another one to keep an eye on, said Gilchrist of UBC, although there is no evidence of seismic activity or gas release.

“However, if it were to erupt, it would be a very significant crisis because Squamish is just below it and Vancouver could probably be affected by ash fall. It would be a very worrisome event.”

Because of the tectonic plates of the region, where the oceanic plate is being thrust underneath the North American plate, Gilchrist said he wouldn’t be surprised if at some point in the future — likely thousands of years from now — there is another explosive or effusive eruption in B.C.

Can volcanoes be controlled?

What makes it challenging to respond to eruptions is the short warning time period, experts say.

“Sometimes you can get a week in advance for some of the eruptions we’ve monitored in the past 50 years or so,” said Gilchrist.

“Other times, it can be almost with no warning.”

And once the eruptions start, there is very little that can be done to control the lava flow, experts say.

But the damage can be mitigated by timely evacuation and having contingency plans in place.

Diverting lava flow away from the built-up areas is another option that has been used in the past but with little success, said Ashwell of U of T Mississauga.

To better respond to the hazard, Gilchrist said it would be helpful to study the history of volcanoes to understand all the expected styles of eruption and dangers associated with them for nearby communities. But even that plan is not bulletproof because of the unpredictable nature of eruptions.

“During an eruption, we can run some models as data comes in and try to predict how the hazards are going to play out,” he said.

But when the eruptions are very large, we are at “nature’s mercy,” Gilchrist added.

“The best thing we can do is have evacuation plans ready to execute and hopefully execute them properly and get people out of the way.”

Comments