By

Max Hartshorn

Global News

Published August 28, 2021

16 min read

When experienced amateur pilot Ron Scott set out from Picton Airport in a Cessna 172 in the summer of 1975, there was no reason to suspect trouble.

The sky was clear. The wind was calm. It was perfect weather for a short pleasure flight over the shores of Prince Edward County. But as his plane made its way over Prince Edward Point, the peninsula at the county’s southeastern tip, something “unnerving” began to happen. Without any sign of turbulence, the plane banked sharply to one side and locked itself in that position.

“It was as if an invisible giant took hold of the wing,” says Scott. “I could not straighten it out.”

Without the ability to counter, Scott feared his plane would flip over entirely and fall into a spin, which at 1,000 feet would have been tough to pull out of. His plane began to right itself after about 10 seconds. Then the same thing happened with the other wing. Somehow, despite all the midair chaos, Scott was able to make it down safely, though he was understandably rattled.

“It shakes you up a bit. Like ‘what just happened?’” Scott, 46 years later, still wonders.

He has flown in just about every kind of weather imaginable, but he has no explanation for what occurred that day.

“It was just totally weird,” says Scott. “I’ve experienced nothing like that ever before or since. And I’ve never heard of anything like that … There are strange things out there.”

His story is hardly an isolated tale.

At nearly the same spot, in 1952, Royal Canadian Air Force pilot Barry Allen Newman plummeted from 20,000 feet into the lake in a P-51 fighter. His body was never recovered.

These days, Prince Edward County is best-known to visitors for its sandy beaches and up-and-coming wineries. But there is a much darker side to the region that few sightseers ever learn about.

Dubbed the Marysburgh Vortex, or alternatively “The Graveyard of Lake Ontario,” the small stretch of water off the shores of Prince Edward County has for centuries played host to shipwrecks, airplane mishaps, strange sightings and mysterious disappearances.

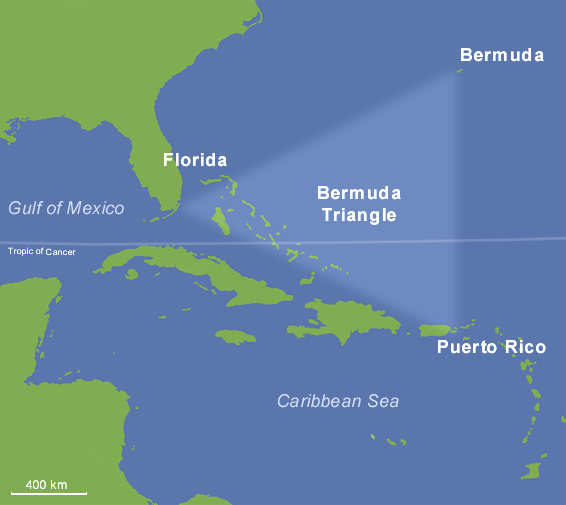

Global News has identified at least 270, and as many as 500, ships that met their watery end in this part of the lake. And at least 40 planes have met a similar grisly fate in and around these shores — a far higher concentration of shipwrecks and plane crashes than can be found in the famous Bermuda Triangle in the North Atlantic Ocean.

On May 28, 1889, the schooner Bavaria entered the final stretch of its journey hauling timber from Toledo, Ohio, to Garden Island, near Kingston, Ont.

The vessel was part of a trio of ships under tow by a steam barge. No sooner did the boats round the edge of Prince Edward County than they were caught in what Capt. Anthony Malone of the barge described in the papers as “a living gale.”

Unable to withstand the force of the heavy winds and mountainous seas, the tow line snapped, sending the Bavaria careening into one of the other schooners. Fearing the worst, Malone circled his ship back to the Bavaria to offer assistance. But there was no one there to assist. The Bavaria appeared to still be in working condition, but the entire crew, including Capt. John Marshall, was missing.

Even more mysterious was when the ship ran aground at a nearby island, it was found to be entirely undamaged, save for a missing lifeboat.

“Everything in the cabin is dry. Even a pan of bread, set in the oven to bake, is still there,” wrote Kingston’s the Daily British Whig.

The Oswego Daily Palladium noted that Capt. Marshall was “a good man, and one not likely to act rashly or without thought.”

What possessed a captain and his crew to jump ship in the middle of a terrible storm? Since Bavaria was carrying timber, it was never at risk of sinking. If the crew had simply stayed on board, investigators concluded, everyone would have been safe.

In total, eight men and women disappeared that day, and their bodies were never recovered. It was as if they had fallen through a crack in the lake, to borrow a common phrase in Great Lakes shipping lore.

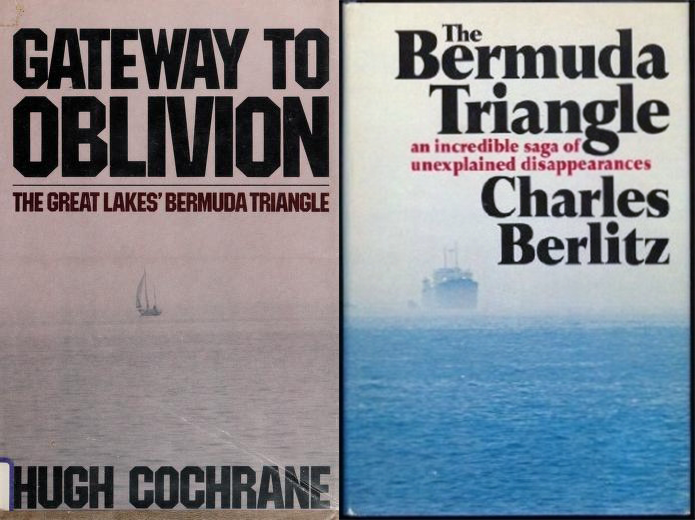

The tragic fate of Bavaria’s crew is one of dozens of mysterious tales from the eastern shores of Lake Ontario that are documented in Hugh F. Cochrane’s 1980 book Gateway to Oblivion.

“The locals were aware of the strange stories that came out of this area,” says Picton-based storyteller and author Janet Kellough.

But it was Cochrane who came up with the name: the Marysburgh Vortex.

The Vortex is generally thought to encompass the eastern part of Lake Ontario, bounded by Prince Edward County on the west, Kingston to the east, and Oswego, N.Y. to the south.

The mysterious region includes, and gets its name from, the southern portion of Prince Edward County, historically known as Marysburgh Township.

“That name took on a life of its own,” says Kellough. “It became a code for anything that didn’t quite go right in your life. Like: ‘I’m late for work, sorry, I got lost in the Vortex.’ Or, ‘I mailed you the cheque. I don’t know what happened. It must have been stolen by the Vortex.’”

Kellough, a seventh-generation Prince Edward County native, has become somewhat of an unofficial chronicler of the legend.

“I wouldn’t call myself an expert, but every time anybody wants to talk about the Marysburgh Vortex they eventually end up coming to me,” she says.

Kellough admits she hasn’t spoken about the Vortex in a long time. Interest in the story has waned in recent years, as the county has become increasingly dominated by a tourism industry that seems largely uninterested in local history.

“I’ve spent my whole life collecting the history and the folklore and the stories and the legends of this place. And now I know why I was doing it. Because if somebody hadn’t done it, they were going to disappear.”

While public interest in Lake Ontario’s maritime legends and lore may be fading, our knowledge of Great Lakes shipwrecks has never been more complete.

Discovering a wrecked ship may conjure up images of divers scouring the water with advanced sonar. But the reality is, the majority of new wrecks are now identified by internet sleuths poring over digitized newspaper archives and vessel registries.

The David Swayze Great Lakes shipwreck file, with additions from maritime historian Brendon Baillod, lists the details and general whereabouts of nearly 5,000 documented shipwrecks across the Great Lakes, though Baillod believes the true number may be as high as 8,000.

A Global News analysis of this database reveals that nearly half of Lake Ontario’s shipwrecks occurred in the eastern section commonly associated with the Marysburgh Vortex, a region that accounts for less than a quarter of the lake’s surface area.

In total, the database lists 270 shipwrecks within the Marysburgh Vortex, although this is almost certainly an undercount, given that the database is incomplete. If Baillod’s estimates are correct, the true number may be closer to 500 wrecks.

This includes storied “disappearances” like the Bavaria and the schooner Picton, as well as hundreds of other water vessels large and small that foundered mostly due to storms and onboard fires.

In all, hundreds if not thousands of sailors and passengers lost their lives navigating the treacherous waters of eastern Lake Ontario.

Thanks to an abundance of cold freshwater, many of these wrecks lay perfectly preserved on the lakebed. These ghostlike memorials, and in some cases tombs, draw diving enthusiasts from all over the world.

There’s the Annie Falconer from 1904, which was found with the captain’s binoculars still on the deck. And there’s the Manola from 1918, which was found with a chipped axe by the door — evidence the passengers tried to hack their way out as the boat sank.

The high number of shipwrecks comes as no surprise to Marc Seguin, Ontario historian and lighthouse preservation advocate.

“It’s been known for centuries as the most dangerous part of the lake,” he says.

Seguin sees no need to resort to occult superstition to explain the trend.

“The cause of the loss of every ship on Lake Ontario could be explained by natural causes.”

According to Seguin, one major reason why so many ships met their untimely demise on the eastern end of the lake is the geography. Much of Lake Ontario is relatively deep and easy to navigate. While you can’t tell by looking at a map, the lakebed tilts up sharply the closer you get to the eastern shore. The deeps give way to a chain of rocky islands and shoals stretching across the lake from Prince Edward County to New York — the somewhat comically named Duck-Galloo Ridge.

This area was especially dangerous in the 19th century, before the era of modern weather forecasting. Storms building up over the lake would come seemingly out of nowhere and send the timber-built sailing vessels careening into this gauntlet of rocky banks and shoals.

Another element that doesn’t help seafaring vessels: a large iron deposit in the middle of the lakebed that can allegedly set compass bearings off by as much as 20 degrees.

These hazards are by no means unique to the Marysburgh Vortex. Rough seas and tight geographies pose a challenge to sailors across the Great Lakes. Rather than fight nature, it was common practice for sailing ships at sea to simply let the wind carry them until the storm blew itself out, even if it took days or weeks. But that doesn’t work on Lake Ontario.

“On the ocean, you can run out a storm,” says Baillod, the maritime historian. “You try that on the Great Lakes, you end up in someone’s cornfield in a few hours.”

It’s one of the cruelest tragedies of Great Lakes shipping — many of the most horrifying disasters occurred within shouting distance of the shore.

In fact, the deadliest shipwreck in Great Lakes history happened just 20 feet from land, when the SS Eastland capsized off a Chicago pier in 1915, killing 844 passengers en route to a company picnic.

The Great Lakes were crucial waterways for the North American economy in the 19th and 20th centuries. They were used to ship raw materials such as coal, iron and grain, and there were often as many ships in the lakes as there were on the entire North Atlantic. More ships sailing in close proximity meant more shipwrecks, which made the area “much more dangerous statistically than any other body of water on earth,” Baillod said.

Sailors would often make bank on especially risky shipments. Grain, for example, needed to be shipped in November after the harvest, during a time of year when storms and lake-effect snow squalls were most dangerous.

“It was just a brutal occupation,” says Baillod. “Thousands of sailors lost their lives, and that was the cost of doing business.”

By the mid-20th century, modern weather forecasting and improved shipbuilding had alleviated most of the hazards of Great Lakes shipping. The last major shipwreck was that of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank off the coast of Lake Superior in 1975, killing 29. Even so, reports of strange incidents in the Vortex never went away, but rather, moved up into the sky.

One of the things Prince Edward County resident Sid Wells recalls most vividly when he first moved there was the shimmering black sky.

“I used to drive out at night just to sit and look at the stars,” he says. “It was absolutely magnificent. You could just touch the stars.”

It was during one of these nights, in 1986, out on the deck at a dinner party in South Bay, when Wells saw something he had never seen before.

“I saw this object just hovering. And it was a diamond shape. It was twirling in the shape of a diamond.”

Wells rushed back inside to grab the other guests.

“I said, ‘Hey, come on, get up on the deck here, you’ve got to see this!’”

For what felt like an eternity — in reality only a few minutes — the guests stared in awe at the glowing white mass that hung over the lake, close to the horizon.

“We knew we were watching something very special.”

Then, as if someone had flipped a switch, it was gone.

For Wells, now 76, the experience was life-changing, and it spurred an ongoing interest in ufology. He would go on to witness at least a half-dozen more strange sightings over the years in Prince Edward County.

“I don’t believe in conspiracies at all. But I believe in things happening that there are no explanations for. And we need to find out explanations,” he says.

Wells isn’t the only area resident to see something over the lake they can’t explain. During the course of our reporting, Global News came across two previously undocumented accounts of UFO sightings from local fishermen.

On Nov. 14, 2017, pilots on a Toronto-bound Porter Airlines flight from Ottawa noticed a large “unidentified airborne object” directly in their plane’s flight path, 9,000 feet over Lake Ontario. The pilots jerked the plane into a dive to narrowly avoid a mid-air collision, giving two flight attendants minor injuries.

The Transportation Safety Board has yet to figure out what the pilots saw that day, but they don’t believe it was a drone.

“We have no idea,” a TSB investigator told CTV News.

Many fantastic sightings on Lake Ontario have clear explanations. A weather phenomenon known as thermal inversion can cause ships and even entire landmasses to appear upside-down or in some cases as if they are floating in the air.

Typically the higher you go in elevation, the cooler it gets. Sometimes, however, the air at ground level can cool more quickly than the air at higher elevations. This creates what meteorologists call a thermal inversion, and can have some bizarre optical effects. Light hitting the warm layers of the atmosphere will curve downward due to refraction, and this can make distant objects loom high above the horizon.

“Inversions can be a regular occurrence on the Great Lakes,” says Global News meteorologist Ross Hull. “It’s all about temperature contrasts, and we live in a part of the world that sees frequent air mass changes during each season.”

On Aug. 16, 1894, residents of Buffalo, N.Y., woke up to the sight of Toronto hovering high over the horizon, according to a Scientific American article published later that month. Despite being located more than 90 kilometres to the south, Buffalonians were treated to a panoramic view of the Toronto skyline in immaculate detail. Even “the church spires could be counted with the greatest of ease,” the Scientific American article said.

Kellough, too, has witnessed the effects of a thermal inversion in the Marysburgh Vortex firsthand.

On one occasion, she and a friend were out at the beach when they heard a Jet Ski ripping past.

“We looked out and he was upside down,” says Kellough. “We knew what it was, it was an inversion, but it was just so distinct. It was crazy.”

When conditions are just right, thermal inversion can produce a rare type of mirage known as a fata morgana, which is about as ghoulish as it sounds. With a fata morgana, the image on the horizon is not merely flipped or lofted up, but is often completely jumbled to the point of unrecognition. An island in the distance might be transformed into a cluster of disembodied shapes that appear to float and dance above the horizon.

Of course, seafarers have historically not received specialized training in optical physics and atmospheric chemistry, so it’s not surprising that fata morgana mirages have been the source of many myths among mariners.

The legend of the Flying Dutchman, a floating ghost ship doomed to roam the open seas for all eternity, is believed to have been fuelled by these sorts of optical effects.

Before Hugh Cochrane identified the Marysburgh Vortex, there was the Bermuda Triangle, a stretch of ocean between Miami, Bermuda and Puerto Rico with an allegedly high incidence of shipwrecks and mysterious disappearances.

Charles Berlitz, scion of the Berlitz Language School empire, is credited with popularizing the legend. His 1974 best-seller The Bermuda Triangle sold nearly 20-million copies worldwide, and transformed the once-obscure bit of nautical lore into a household name, spawning an army of imitators in the process.

The Bass Strait Triangle in Australia, the Broad Haven Triangle in Wales and the Bennington Triangle in Vermont are just a few examples of the triangle boom of the 1970s and ‘80s.

Even the term “Bermuda Triangle” has become synonymous with the unexplained, and finds itself attached to places nowhere near Bermuda. There is the Alaskan Bermuda Triangle, the Mexican Bermuda Triangle, the Romanian Bermuda Triangle, the African Bermuda Triangle — even the Bermuda Triangle of Space.

It’s possible to view Cochrane’s Marysburgh Vortex as an attempt to cash in on the popularity of the Bermuda Triangle by transposing it onto a Canadian locale.

It would be hard to believe that Cochrane was not influenced by the Bermuda Triangle legend. Both stories document a pattern of disappearing ships and planes over a roughly triangular body of water. Even the cover of Gateway to Oblivion is a mirror image of Berlitz’ original.

Still, many of the shipwreck stories featured in Gateway to Oblivion have been part of local lore, long before the Bermuda Triangle ever existed as a concept. And Cochrane writes with the breathless cadence of a true believer, blending densely packed historical anecdotes with an elaborate set of pseudoscientific explanations that are hard to pin down.

Cochrane himself, who, according to an acquaintance, passed away in 1999, is an elusive figure. Attempts to track down additional biographical details have been futile. Perhaps, as one Facebook commenter suggested, “the Vortex got him.”

Regardless of what became of the man, the legend of the Marysburgh Vortex lives on in the hearts and minds of Prince Edward County residents like Janet Kellough.

“There’s something very special about that area, and I think anybody who’s spent any time close to it feels that.”

Whether or not the Vortex is the result of supernatural forces is of less importance to Kellough. There are many mysterious places on this planet. But the history, geography, culture and experiences that inform this legend are actually quite familiar. They are the texture that makes life in this small corner of southern Ontario unique.

“It’s an absolutely wonderful story. And we have too few wonderful stories in this world.”

Comments