Edmonton’s opioid crisis is spiraling out of control, according to those closest to it, and people are now dying every day.

“Across the board we are just seeing so, so many more patients come in with opioid poisoning,” said Dr. Shazma Mithani, an emergency room physician at the Royal Alexandra Hospital.

“We are seeing two deaths a day in Edmonton, on average.”

Mithani said even within the last six months, she’s noticed things have become dramatically worse while working at the hospital in central Edmonton.

“We are continuing to see a steady rise… it seems like it’s just continuing to get worse.”

Dwight Barker lives a block away from the Boyle McCauley Health Centre, which is north of the downtown core on 96 Street near 106 Avenue.

He has not used drugs in nearly a year and counts recovery as one of the greatest achievements of his life — but opioids remain a constant, unwelcome companion in his world.

Barker has used heroin and crystal meth in the past, but said he would never touch fentanyl.

“That’s the scariest drug out there. By far, I think. The fentanyl right now is much stronger than when I used to do drugs.”

He rides his longboard around the McCauley neighbourhood and says he sees the destruction of drugs like fentanyl everywhere he goes.

He hears ambulances day and night in his back alley.

He watched as paramedics attended to an overdose call at Edmonton City Centre mall and then spotted another crew around the corner seconds later.

He has has seen community members die.

“I used to live on the street about a year ago. A lot of my friends have just disappeared… I don’t want to ask anyone about it because I don’t really want to get the final truth.”

Get weekly health news

Diverting resources at inner city health centre

Staff at the Boyle McCauley Health Centre have had to divert essential services like pre-natal and diabetic care to keep up with the unprecedented level of overdoses.

Francesco Mosaico is the medical director at Boyle McCauley. He said the introduction of fentanyl into the city’s drug scene completely changed the landscape of care.

“I think there’s a sense of desperation amongst clients who are affected by this and then the impact it’s also having on staff,” he said.

“This is an emergency. We have never seen numbers like this. We’ve never seen a more profound impact on the community and the resources required to response to this.”

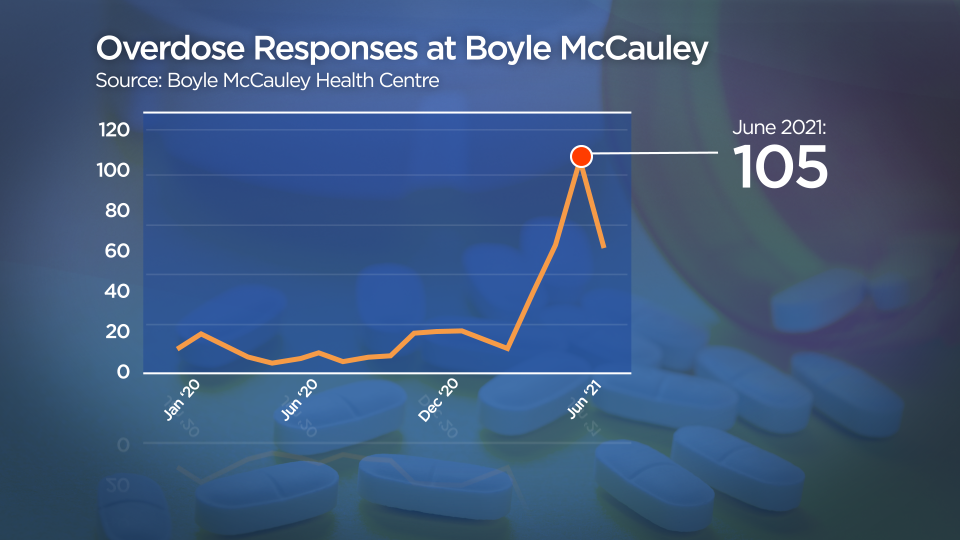

From January 2020 to March 2021, the highest number of overdoses in one month was 20. In April, numbers started to climb, hitting a peak of 105 in the month of June alone.

Executive director Tricia Smith said saying the number out loud gives her chills.

“We are only open five days a week, eight hours a day. We only have staff to respond those hours. The number of overdoses that happen on an hourly basis for 40 hours a week for four weeks… it’s almost an overdose an hour,” she said.

The health centre statistics offer a glimpse into the wider opioid crisis across the city.

Edmonton Fire Rescue Services is also seeing a huge increase in the overdose calls crews help with.

In 2019, crews responded to more than 1,100 overdose calls. In 2020, it doubled. As of August 2021, EFRS is already at more than 3,000 calls.

These patients might then end up inside Mithani’s emergency room — it’s the closest one to the city’s core, where many social service agencies are concentrated.

Smith though, says the opioid crisis goes beyond the inner city.

“Overdoses are happening across the city. It’s happening in the suburbs. It’s happening in people’s homes. Support is needed across the city in every area.”

Elaine Hyshka, an assistant professor at the University of Alberta’s School of Public Health, said the government needs to disrupt a drug supply that has become more dangerous since the COVID-19 pandemic forced borders to close.

“There’s a lot of fentanyl and other non-synthetic opioids that are trafficked from Mexico and come north to Canada,” Hyshka said earlier this summer.

Drugs moving through illegal channels are being cut or adulterated to maintain supply, she said.

Mosaico said he believes if Edmonton started to see this level of overdose or near fatal death experiences from any other medical condition, there would be a markedly different response to the crisis.

“Part of it is a little bit grounded in ideology and what we value as a community,” Mosaico said.

“I think what we don’t realize is that this affects everyone. We are all interdependent in our well-being. It’s not just economics. It’s not just the humanitarian aspect. That’s why it’s important to respond to this like we would any other health crisis.”

Signs of opioid poisoning are slow or no breathing, being unresponsive to a voice or to pain, choking or vomiting, cold and clammy skin, tiny pupils or seizure-like movement or rigid posture.

Naloxone kits are free and can be found at over 2,000 community sites and pharmacies in the province.

Each kit is equipped with a rescue breathing mask to put on the person who is overdosing, which is used before the naloxone is injected. The kits have three vials and needles that can be injected into the thigh or shoulder.

— With files from Sarah Komadina, Global News and Fakiha Baig, The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.