The pandemic’s third wave has seen daily case counts in Canada rise to record highs despite several provinces imposing new restrictions, and some experts are pointing to ring vaccination — a strategy deployed in the eradication of smallpox — as a template for how to focus limited vaccine supply to have the greatest impact.

While experts say COVID-19 and its spread pose unique challenges in deploying ring vaccination by the book, the principles behind it can guide vaccine prioritization by creating a “ring” of vaccinated protection around hot-spot regions or even specific workplaces.

Ring vaccination as a targeted strategy

In its simplest terms, ring vaccination involves identifying and vaccinating the “ring” of individuals in contact with an infected individual in order to protect them and to suppress further transmission.

“I would define ring vaccination as a method for deploying or distributing vaccines that is strategic in how it chooses to connect the vaccine to people that could benefit from it most,” says Darrell Tan, an infectious diseases physician at St. Michael’s Hospital and clinician scientist in its department of medicine.

Tan, who is also an associate professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, says it’s a proven concept that was successfully used to eradicate smallpox.

The World Health Organization says smallpox, which it declared eradicated in 1980, is “the only infectious disease to achieve this distinction.”

More recently, the strategy has been deployed in response to various outbreaks of Ebola virus disease.

However, ring vaccination is best suited at targeting vaccine supply to suppress outbreaks as they pop up, rather than addressing widespread community transmission.

When it comes to COVID-19, the extent of transmission at this point in the pandemic poses a challenge.

Get weekly health news

“In regions where we have already significant community transmission going on, I’m somewhat doubtful how much (impact) it would bring,” says Jörg Fritz, associate professor at McGill University in the department of microbiology and immunology.

“If community transmission is relatively low and you have a targeted outbreak in a certain setting, being that a workplace, a retirement home, a school and its surroundings, I think it makes sense.”

A ring vaccination pilot project was launched in Montreal last month, for parents/guardians and staff at select school communities in three postal codes that were seeing a large number of variant cases.

Fritz says “community transmission has been going down since then. It’s hard to say if this was clearly linked to that ring vaccination strategy, though.”

Outside of the challenge of the sheer volume of cases, timing is also crucial.

As Tan explains, vaccines for COVID-19 begin to exert their effect most clearly after roughly two weeks. At the same time, the incubation period for COVID-19 can be up to two weeks, but is on average about five days.

“That means that if we have identified someone right now who has unfortunately been diagnosed with COVID-19, the people around them who are at risk — that ring of contacts — that five-day clock has already started ticking,” he says.

“So even if we’re successful at swooping in with a vaccine and can recommend it and they accept that vaccine at the moment, we wouldn’t expect that vaccine to adequately protect that particular person, that ring member, from showing manifestations of the infection because we need two weeks roughly for that vaccine to take effect.”

As a result, Tan suggests also moving to the second ring, or the index case’s contact’s contacts.

“Those people we may have enough time to deliver the vaccine to them right away and actually lead to protection of those individuals.”

Because it takes time to ramp up an immune response, Fritz suggests vaccination should be coupled with some kind of lockdown.

'The principles are what's important here'

In its truest form, ring vaccination may not be the best way to address COVID-19 transmission, but experts say the spirit of ring vaccination — a focus on targeting vaccine supply to where vaccination would have the greatest impact — has value.

“Because vaccines are unfortunately so scarce right now, we have to be thoughtful… That means bringing the vaccines to the individuals, the communities, the locations, the settings where we have the most transmission, where we have the most risk, and therefore where we can have also the most benefit,” says Tan.

“We need to acknowledge that risk is not equally distributed in our population because of a whole host of structural, systemic inequities. And we need to respond to that.”

Outside of the human cost, a focused and targeted approach could also prevent financially costly shutdowns due to outbreaks at workplaces, Fritz suggests.

“We had outbreaks in meat processing places, I think it would be good to prioritize these places and have them vaccinated as quickly as possible in order to have somewhat the balance of, you know, containing community transmission while being able to maintain economic productivity.”

Some provinces have begun moving to further target vaccinations.

In British Columbia, teachers and other education workers in the Surrey School District were among the first in the region to be given priority access to the AstraZeneca vaccine in late March.

Earlier this month, Ontario began reallocating some of its vaccine supply to start offering vaccines to all adults in “hot spot” neighbourhoods, based on postal codes.

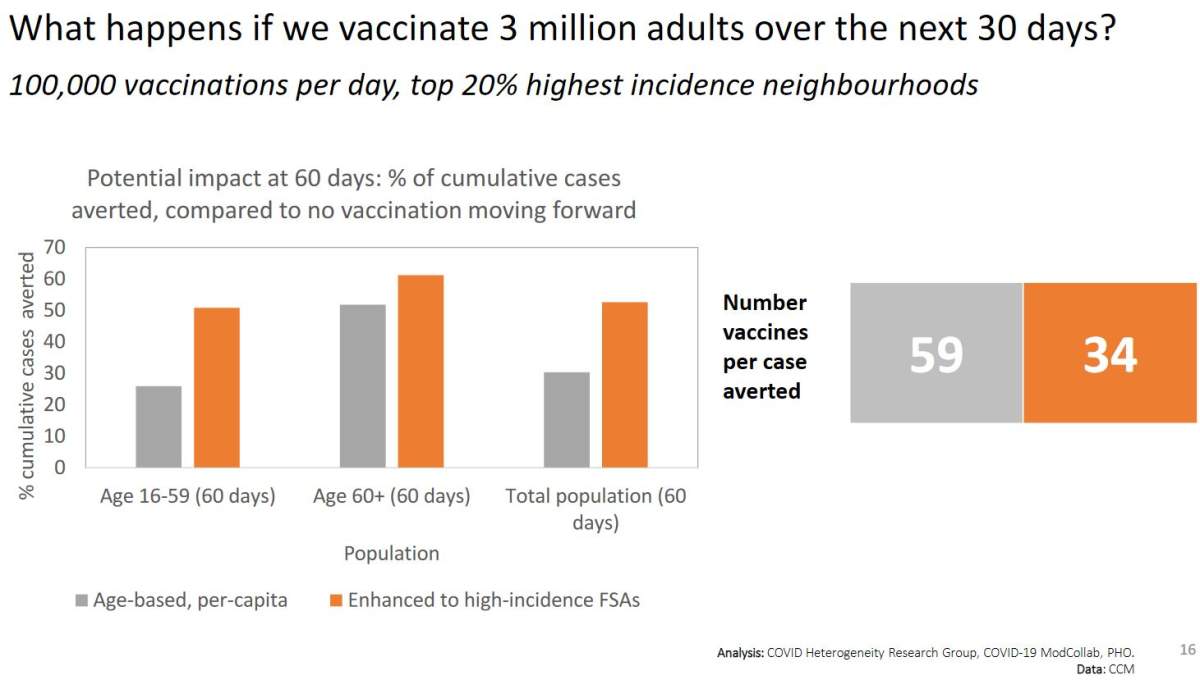

On April 16, the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table released data comparing the predicted impact of vaccinating three million adults over the next 30 days based on age and based on high-incidence neighbourhoods.

The data suggests that under an age-based approach, it would take about 59 vaccinations to avert one case of COVID-19.

However, if vaccination was targeted to all adults in postal codes where transmission is highest, it would take only 34 vaccines to avert one case.

Manitoba is expected to take a similar “hot spot” approach, with details expected on Friday.

The various forms of targeting vaccine may not fit the exact definition of ring vaccination, but as Tan says, “the principles are what’s important here.”

— with files from The Canadian Press’ Steve Lambert and Global News’ Richard Zussman and Simon Little.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.