In July 2019, Mehmet Tohti was just hours away from speaking publicly to politicians about the Chinese government’s horrific abuse of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang when he received a message on Twitter:

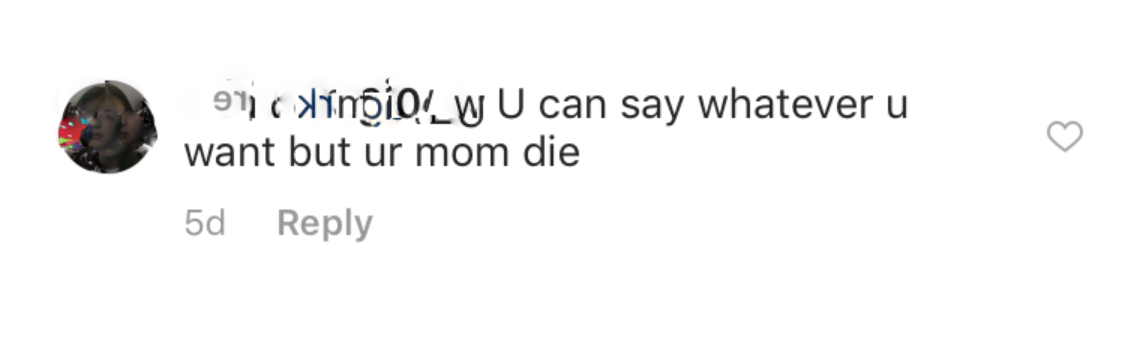

“Your f—ing mother is dead,” it read.

Tohti had lost contact with his mother in late 2016, three years earlier. He had started to become more vocal about the mass detention and abuse of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang, publicly calling it a genocide and alleging the existence of concentration camps.

“And then my mother and 37 family members, close relatives, disappeared,” Tohti said.

“Since October 23, 2016, no phone, no message…nothing.”

He never heard from his mother again.

“I love her so much,” Tohti said softly.

His story is just one of many for activists who speak out against the Chinese government in Canada. Despite being separated by an ocean, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its supporters have methods of keeping activists in Canada under their thumb — and there’s very little that Canadian law enforcement can do about it.

Cherie Wong is painfully aware of this reality.

She had already faced repeated death and rape threats. Knowing full well the kind of intimidation and threats that activists critical of the Chinese government face, Wong had a friend book her Vancouver hotel room under a different name. It was January of 2020, and she was in town to launch her organization, Alliance Canada Hong Kong, which fights for the autonomy of the region.

Sitting in her hotel room, the phone began to ring.

When she answered, she says she was greeted by an intimidating voice. It kept repeating, “we’re coming to get you.”

“It was a very threatening tone on the phone, telling me that ‘we know where you are, this is your room number, and we’re coming to get you,’” Wong said.

She had no idea who it was, but they knew her name and hotel room number — despite the fact that she had taken precautions to shroud that information from anyone contacting the hotel.

“I sat in my room and just started shaking, realizing that I could be in very real danger and not knowing what to do,” she said.

She said she contacted the police, but they told her there was nothing they could do about it. This is a key part of the problem, Wong said: the intimidation activists face often falls into a legal grey area, where there’s very little Canada can do.

Speaking to a parliamentary committee on March 11, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki said those feeling pressure from China can call the RCMP’s national security tip line. That line is open to any and all national security tips and Lucki acknowledged that they “tend to get a lot of tips that aren’t relative to national security or law enforcement.”

“What dissidents face in Canada is often on the grey area of criminal harassment and just discomfort that you feel (in) daily life,” Wong said.

“I can assure you most of the harassment that I personally have experienced, aside from the very extreme death and rape threats, are not criminal activities. But they equally create the same threat for me and my family, whether here in Canada or in Hong Kong.”

For example, Wong said, activists who speak out can often expect their families to get a “tea visit” from government officials back home in China.

Get breaking National news

“They come and knock on your door and say, ‘we’re coming in to talk to you about your family,’” she explained.

As officials sit down and drink tea with your relatives in China, they offer a chilling warning, according to Wong: “Your family from Canada seem to be very active nowadays. Maybe you should tell them to stop.”

“How do you report that to the RCMP?” Wong asked.

That’s exactly the fear that was front of mind as Tibetan-Canadian Chemi Lhamo welcomed Hong Kong students to her office when she served as student president of the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus.

She said other students often stood poised outside the door, snapping photos of the Hong Kong students who entered.

“That means that their families back home would also be subjected to threats, so I had to meet them, actually, in secrecy,” Lhamo explained.

“People would actually come in wearing their masks…like a full head on, sometimes clown masks and sometimes V for Vendetta-type masks, to enter my office to be able to talk to me. And so because of that, whether it was self-censorship or the intimidation tactics, either way, it really came in the way of me being able to actually help them.”

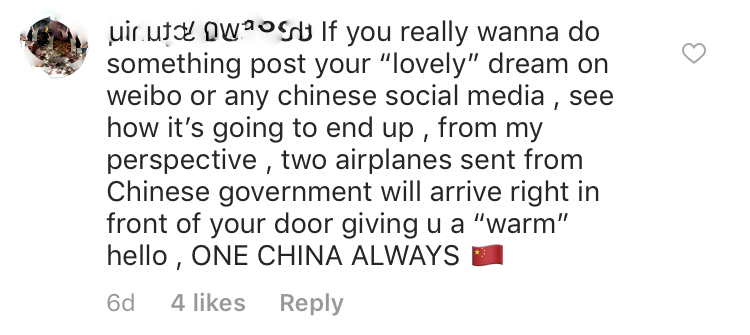

Lhamo understands why these people might want to hide their identities. When she was first elected student president, her stance in favour of Tibet’s liberation garnered the attention of supporters of the Chinese government — and a campaign of harassment ensued.

Tibet has been under China’s occupation since the 1950s. China’s military invaded and took over the land, brutally cracking down on any pushback from the Tibetans and forcing their leader, the Dalai Lama, to flee to India. In the years since, Tibetan culture has been eroded and any pursuit of Tibetan liberation has been met with prison time, violence and repression.

China, meanwhile, insists the Tibetans are happy and prosperous — but they won’t allow Western journalists or politicians to enter the area and make that determination for themselves.

Lhamo’s grandparents walked on foot over the Himalayas to give her parents a better life in India, where she was born. As she rose to prominence in the University of Toronto’s student government, pro-China supporters flooded her social media with threats.

- Veterans Affairs demands repayment of some benefits; process shocks veterans’ advocates

- Air Transat to begin cancelling flights Monday. What you need to know

- Will U.S. restart stalled trade talks with Canada? ‘We’ll see,’ says Trump

- Air Transat pilots gear up for strike as union issues 72-hour notice

“I was attacked by these thousands and thousands, I would say over 10,000 messages and comments, which were not just hate speech. I had death threats, rape threats, and they were against me, but also targeting my family members,” Lhamo said.

One comment was similar to a threat Tohti had faced. A comment posted on her Instagram: “your mom is dead.”

She said she immediately called her mother, checking in during the middle of her mom’s workday to see whether she was alright. She was fine, although Lhamo said she was a bit confused about why her daughter was asking.

“Those were the moments where… I realized how much of a threat the Chinese government can still be,” Lhamo said.

“That’s just a peek into the life that I had to live because of the Chinese state influence, despite being born in India and raised in Toronto.”

But Canadian law enforcement agencies still struggle to help address constant disruptions in the lives of activists like Lhamo, Tohti and Wong. Speaking on March 11, Lucki explained the RCMP receives 120 tips daily on its national security tip line — but that many of the tips can’t be addressed.

“People might feel, for example, a threat. If it doesn’t meet the threshold of a criminal offence, then we normally can’t deal with it, in that sense,” Lucki explained.

She said that sometimes, if the tip doesn’t quite meet the threshold of a national security threat, the RCMP will pass off the case to local police services — but only if there’s a Criminal Code violation involved, such as uttering threats.

Callers can also sometimes find their tip passed along to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). But while there’s multiple national security agencies available to help, Wong said very few can actually do anything to stop the intimidation.

This is because Canada doesn’t have laws against “clandestine foreign influence,” according to Stephanie Carvin, a Carleton University professor and former CSIS analyst.

Clandestine foreign influence refers to secretive efforts by a foreign government to influence policy or action abroad — in layman’s terms, spy missions.

“There’s laws against targeted harassment. There’s laws against intimidating people and uttering threats. But by and large, this becomes very, very hard to prosecute,” Carvin said.

“Sometimes CSIS will interview these individuals just to get a better picture of what’s happening. But at the end of the day, there really isn’t a lot we can do unless we know that these activities are specifically linked to individuals who may be at a consulate or embassy.”

It’s a reality that’s familiar to Wong.

“Many members of our community, including myself, have spoken with members of local police…some of us have been in touch with CSIS agents. But the general consensus from all of these law enforcement and intelligence agencies is ‘there’s nothing we can do to help you individually,’” Wong said.

But there are things the Canadian government can do to help, she said. They could provide resources to the victims of this harassment in languages like Cantonese, she suggested, as not all members of diaspora communities speak French or English.

Both Wong and Tohti also called on the government to create a registry for foreign agents working in Canada.

It would “bring to light that there are foreign actors active here in Canada, whether Chinese or otherwise, carrying out state sanctioned operations,” Wong said.”

But while they wait for the government to take action, the threats against critics of the Chinese regime continue.

Tohti said he’s had cars parked outside of his house for weeks on end — ones that no neighbours recognize. Individuals have come to his front door in Ottawa asking questions about his activities.

Wong said her internet often fails when she gets on the line with members of Parliament to discuss the plight of Hong Kongers.

Chinese officials continue to visit family members back home in China for ‘tea.’ They often do so after individuals like Wong speak to the media, she said.

And to this day, Tohti still doesn’t know what happened to his mother.

“And I don’t think the Canadian government understands, truly understands the struggles that Chinese dissidents have been struggling with, not only in the past year, but in the past few decades.”

But, she said, she won’t stop speaking out.

“I’m willing to risk my own safety and my own security if it means that Hong Kong and Canada can feel a little safer.”

Tohti, who has had his entire extended family detained in Xinjiang as he spoke out about the abuses, also stood firm in his convictions.

“There’s nothing in my hand to change the fate of my relatives. Even (if) I stopped today. It wouldn’t change anything. Probably, the Chinese government would increase the pressure, by thinking that the pressure works here. So let’s double up,” he explained.

“It is tough. It is tough.”

But, he said, it’s the right thing to do.

“Despite the risk, despite the danger, you put yourself and you put your family members (in), you have only one choice,” Tohti said.

“To do what is right, and stand on the right side of history.”

“Such allegation has no factual basis at all, it is nothing but self-hype and malicious slanders, attempting to sabotage prosperity and stability of Hongkong, Xinjiang and Xizang.”

Comments