They were students. Professors. A physician. A soccer player. Newlyweds and sisters.

When Ukraine International Airlines Flight PS752 was shot down by the Iranian military over Iran on January 8, 2020, it killed 176 passengers and crew.

Among them was a number of Canadians and Edmontonians. One year after this Canadian tragedy, the deaths of these 13 people are still felt deeply, their lives cut short, their promise of a brighter future extinguished.

Arash Pourzarabi, 26, and wife Pouneh Gorji, 25, were still very much in the honeymoon phase of their marriage when they boarded flight PS752.

The couple had married in a big wedding in Tehran just a week earlier on New Year’s Day. Gorji wore a strapless white dress and flowing veil she and several of her friends excitedly picked out months earlier at a small shop in Edmonton.

The newlyweds were headed back to Edmonton to continue their studies at the University of Alberta where they were both pursuing master’s degrees in artificial intelligence. They were also planning to have a small wedding celebration with friends in Edmonton who couldn’t make it to Iran.

“I’m still looking forward to that,” friend Amir Samani told Global News in January.

In her studies, Gorji was using machine learning to improve the diagnosis of ailments like hip dysplasia, glaucoma and fatty liver using ultrasound machines. That work was paused following her death but her colleagues were determined to finish it in her honour.

She was credited posthumously in the paper she co-authored on the subject. The couple also received posthumous degrees from the U of A last summer. Despite the promising research both Pourzarabi and Gorji were working on, friends say the thing they were both most passionate about was each other.

“If you met them even once, you could tell that these two belong together,” friend Amir Forouzandeh said in describing the couple.

Daria, 14, and Dorina Mousavi, nine, grew up in science labs at the University of Alberta. It’s where their brilliant parents Pedram Mousavi, 47, and Mojgan Daneshmand, 43, were both professors.

Daneshmand was an associate professor of electrical engineering and Canada Research Chair in radio frequency microsystems. Her husband was an engineering professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and held the NSERC-AI Industrial Research Chair in Intelligent Integrated Sensors and Antennas.

Both were working on research projects using radio frequency to change the world. It was technical work and not easy to understand but those who did say without the pair, there is a hole.

“It’s such a big loss — not only for Alberta, not only for Canada — for everyone working in this field,” said colleague Hossein Saghlatoon. “I was at the department and I saw some faculty and they just got the news.

“Everyone was in tears. All the students were in tears, all the faculty members, everyone.”

The couple was well known not just for their technical innovations but also for their willingness to help newly arrived Iranians settle in at the university. Pedram had been responding to emails from students and co-workers up to the moment the plane took off.

“One day I talked about how my wife is struggling here as a newcomer staying home and she said, ‘Invite her, let’s talk,'” said student Sameri Deif.

“I was really surprised how she can take her students as a package. You, your research, your family, everything. She took care of everything in your life.”

More than anything, Mousavi and Daneshmand were devoted parents.

Dorina was described by her soccer coach as smart, inquisitive and safety conscious. One time she showed up for practice with a lollypop in her mouth. When her coach told her she needed to get rid of it, Dorina explained that she needed the sugar to give her energy.

A scholarship was created in Mousavi and Daneshmand’s names to fund two graduate students of Iranian descent.

As an obstetrician and gynecologist at the Northgate Medical Clinic in Edmonton, Shekoufeh Choupannejad, 56, was beloved by her patients and colleagues.

Get daily National news

“Whenever there was any sort of fundraisers within the Iranian community where they’d be selling food for a charitable cause, their fridge was always filled with those items,” said Daniel Ghods.

Ghods was dating Choupannejad’s youngest daughter Saba Saadat. Saba, 21, was about to graduate from the University of Alberta with a bachelor of science in biological sciences. Ghods said her next step was medical school.

After her death, Ghods found out that Saba had been invited to interview for several programs — a devastating piece of news.

He was close with her sister Sara, as well.

“She was one of my sisters, always there to listen. She was such a kind heart. Even now, when we speak with friends, they just sort of miss the sense of support that they received, both from Saba and Sara in terms of emotional support, always being there to listen and providing reasoned guidance.

“It was as if they were a sponge. You know, they would absorb all of our problems and just be there to help us through anything.”

Saba received a posthumous degree from the U of A. Sara, 23, had graduated from the school in 2019 with a science degree in psychology.

She had just moved to San Diego to start a clinical psychology program but had travelled with her family to Iran over the winter break.

Ghods has become an advocate for justice in the last year.

“One of the things that the families are calling for is for Canada to find a mechanism to take the investigation out of the hands of the perpetrators of this crime, because that just does not make any sense,” Ghods said of Iran overseeing the investigation.

“Peace comes sort of following that because we know from Iran we are not going to get any sort of straight answers.”

Mohammad Mahdi Elyasi, 28, had dark curly hair and sported a big smile in every photo. He had completed his master’s degree in engineering at the University of Alberta in 2017.

He specialized in fluid turbulence and used that knowledge as he co-founded a startup in Toronto — ID Green uses drones in crop monitoring for potato farmers.

Friends described Elyasi as a motivated person who loved to hike and play guitar. He and his friends would go head-to-head in Tetris competitions. He also went out of his way to help immigrants feel more comfortable by teaching English to other Iranians new to Canada.

“He really liked to help friends,” Sen Wang wrote in an online U of A tribute. “Like, some people would say ‘I’m going to help you’ but they don’t put in that much effort.

“He actually put all his effort into helping other people solve their problems.”

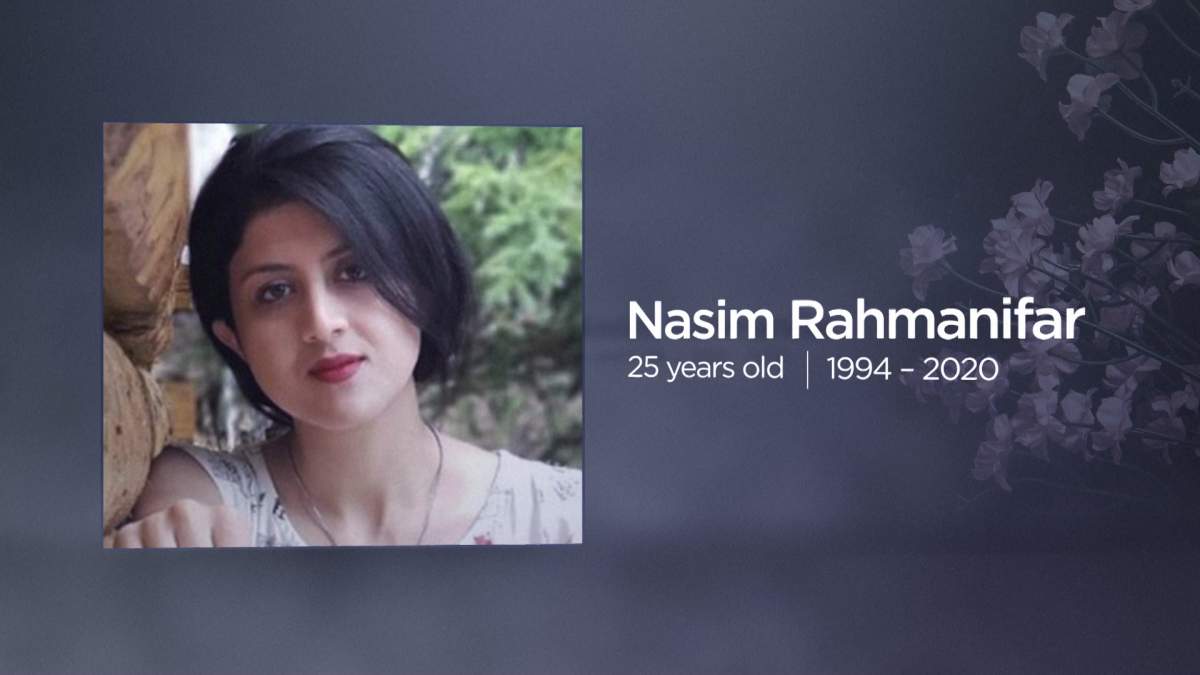

For months after the downing of the plane, a black and white smiling photo of Nasim Rahmanifar, 25, remained above her desk at the University of Alberta.

Her office was in a shared room with orange shag carpets and her desk, largely untouched in the months since her death, was the most organized. Above it hung a postcard that read “your future looks so bright, you have to wear shades.” But that bright future was never fully realized.

The desk was steps away from the lab where she was conducting research in accessible and wearable technology to help wheelchair users prevent injury and strain.

Her supervisor, Dr. Hossein Rouhani, found her work so promising he had offered her a transfer to a PhD program. It would be more work than what she was currently doing in her master’s in mechanical engineering, but Rouhani believed Rahmanifar was up for the challenge.

She was still considering the offer when she flew home to Iran for winter break.

“I never forget, she expressed how excited she is to go back to Iran to see her family for, just so you know, end of semester vacation,” friend Reza Akbari told Global News.

Friends said part of that was homesickness, but the other part was that she didn’t like the cold weather of an Edmonton winter.

“It’s hard to believe that this person doesn’t live anymore,” Akbari said.

Rouhani says Rahmanifar’s death has forever altered the way he teaches.

“It changed the way I look at every single student, graduate student or undergraduate,” he explained.

“We should not consider them as as numbers. We should not consider them as visitors or as tuition fee payers.

“We should see them as precious treasures that we have here.”

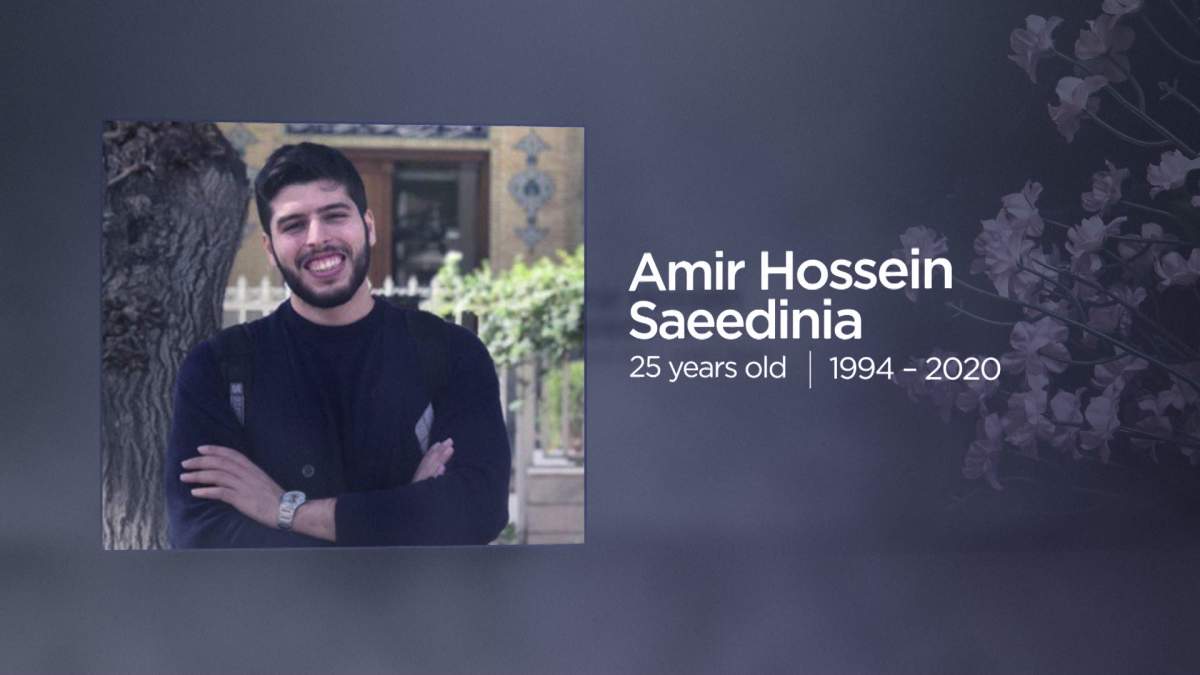

After completing a master’s focused on biomedical engineering in Iran, Amir Hossein Saeedinia, 25, was about to start his PhD in mechanical engineering at the University of Alberta. He would join his long-time friend Nasim Rahmanifar at the university.

“Amir was really excited for the opportunities to study here at the university,” his PhD supervisor James Hogan told the U of A in an online tribute to Saeedinia.

“He was even excited about experiencing our cold weather.”

Hogan described being so impressed by Saeedinia’s passion for the work, he created a job for the Iranian — even though there technically wasn’t one available.

Saeedinia’s research focused on finite element modelling of the material behaviour of coatings. It was work he hoped would improve the oil and gas industry by mitigating wear and corrosion in pipes.

Outside of education, his friends remember him for his huge smile and enthusiasm. In June, his loved ones gathered around picnic tables at Hawrelak Park to celebrate what would have been his 26th birthday.

His mother, father, brother and aunt travelled to Canada in March 2020 seeking refugee status, saying they were being threatened by authorities in Iran. The family had been outspoken in their calls for justice and for Iran to be held responsible in the downing of the plane.

Described by her husband as a planner, Elnaz Nabiyi, 30, and her husband Javad Soleimani had just started planning to expand their family. She wanted a little girl with long flowing hair who she could raise well with a good education.

After moving to Edmonton from Iran, the couple were both completing their PhDs in operations management at the University of Alberta, where Nabiyi received a posthumous degree in the summer of 2020.

The couple had plenty in common, but Soleimani always felt a bit inferior.

“Sometimes I think I didn’t deserve to have Elnaz. That’s why I lost her,” Soleimani told Global News.

Aside from being brilliant, Nabiyi is described as elegant, creative, artistic and friendly with an eternal smile. Soleimani said there would be times where she would drag him outside for a walk in the snow to enjoy the little things in life.

“She was a person living in the moment, you know?”

Her husband produced a documentary called Dear Elnaz about the crash and his ongoing quest for justice.

“To have a closure we need to know the truth about the downing of Flight 752,” Soleimani said. He and other families whose loved ones were on the plane created an advocacy group and have lobbied governments in Canada and abroad to hold Iran to account.

Soleimani said his wife taught him to be skeptical and critical, something he continues to do in her honour.

“I really regret that I couldn’t have more time with her. One of my biggest regrets was that I wasn’t on that flight with her.”

— With files from Karen Bartko and Emily Mertz, Global News

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.