Bill Horrace lived in a modest house in London, Ont., with a maple tree out front that sheltered it from the street. The neighbours knew him as a father and the owner of a Toronto hair salon.

They didn’t know about his past, that before arriving in Canada he served for years in the Liberian forces of warlord Charles Taylor, now a convicted war criminal.

But Canadian war crimes officials knew.

Six months after he used false passports identifying him as “John Daye” and “Alexander Haines” to travel to Toronto, Canada’s war crimes unit made it known he was not welcome.

“By virtue of his voluntary membership in the Liberian Armed Forces, there are serious reasons for considering that Mr. Horrace committed, or was complicit in war crimes,” they wrote in a letter dated Feb. 12, 2003.

But for 18 years, Horrace fended off the government’s attempts to remove him from Canada, filing four appeals in the Federal Court — the last of which was still unresolved when he was fatally shot during a home invasion.

His death last month has so far led to charges against a 22-year-old man, Keiron Gregory, who was arrested on Tuesday. Gregory’s police officer father and two alleged accessories have also been arrested.

Police do not suspect the killing was linked to Horrace’s past in Liberia.

But the case has put a spotlight on Horrace, and raised questions about how Canada deals with those suspected of having committed war crimes before arriving in the country.

A week after the killing, asked why Canada had failed to bring Horrace to justice, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told reporters: “That is a question on which we will be following up as a government.”

Officials later said no formal review was, in fact, underway, but the government’s interactions with Horrace are detailed in scores of documents obtained by Global News that a former immigration enforcement officer said pointed to a larger problem.

“This is something that just keeps coming up again and again with individuals of similar character and similar backgrounds from different parts of the world that come here and make a claim and are found not to be refugees, are ordered removed but remain,” said Kelly Sundberg.

Now a professor at Calgary’s Mount Royal University, Sundberg said what he found most concerning was that the process worked in that Horrace was flagged early on for war crimes, and yet he was never removed from Canada.

“It’s troubling,” he said.

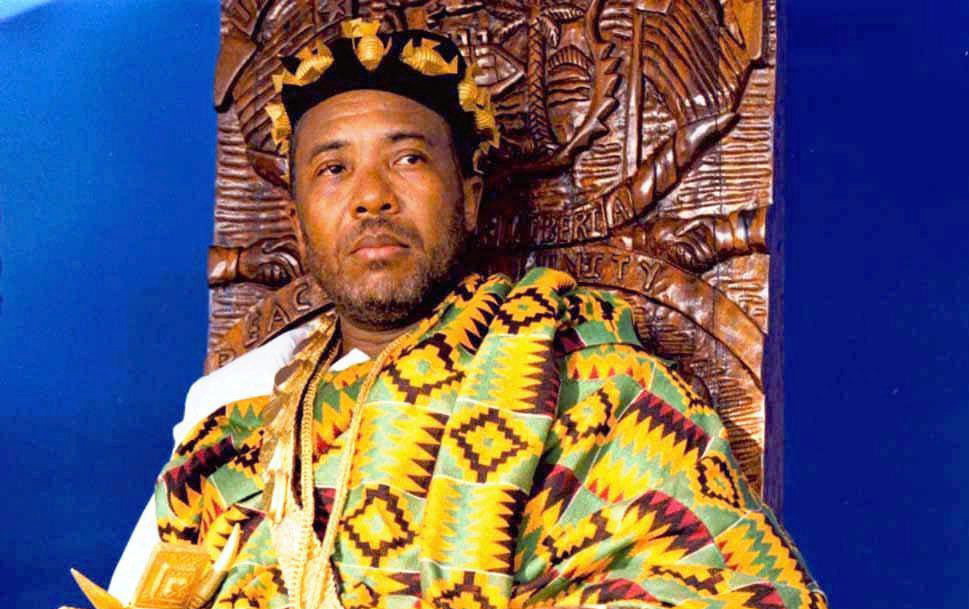

The Liberian civil war was infamous for its atrocities, but particularly for its widespread use of child soldiers. Crossing into Liberia from Ivory Coast in 1989 to topple the regime of Samuel Doe, Charles Taylor’s forces relied heavily on what became known as Small Boys Units.

Hundreds of thousands of deaths later, Taylor became Liberia’s president in 1997. Within two years, the armed conflict resumed and, accused of fuelling civil war in neighbouring Sierra Leone, Taylor went into exile in Nigeria.

Get daily National news

On Aug. 2, 2002, after stops in Ivory Coast, Spain and Portugal, Horrace arrived in Canada. A month later, he filed a refugee claim that said he was studying business at the University of Liberia in 1990 when Monrovia “became a war zone.”

He would have been 13 when he claimed to have started his business degree. The documents do not explain why someone that age would have been at university.

- Carney unveils ‘Buy Canadian’ defence plan, says security can’t be a ‘hostage’

- Rhode Island shooter killed ex-wife, son before bystanders intervened: police

- Canadian immigration officers investigating hundreds identified by extortion task force

- ‘Canada can broker a bridge,’ Carney says on new trading bloc efforts

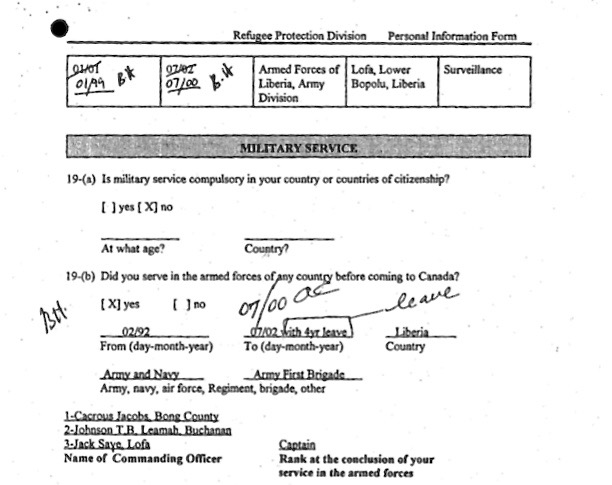

He enlisted in the Liberian armed forces in February 1992. He wrote that he needed money and wanted “to assist my fellow Liberians in restoring peace to the country.”

According to Horrace’s account to Canadian immigration authorities, because he was university-educated and a committed Christian, the army made him an army chaplain and sent him to Gbanga, the base of Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia. He would have been 16 at the time.

He denied ever carrying a weapon or even seeing the front lines. All he did, he claimed, was “pray for, preach to and counsel military personnel.” Later, he said, he helped “coordinate relief efforts by various non-governmental organizations.”

During a leave of absence in 1996, he said he studied auto repair and did volunteer work until the army ordered him back to service in 2000 in Lofa, where he said he “continued my role as a Chaplain.”

But he claimed he learned from civilians the military was conducting beatings, rapes and thefts, and that when he raised the issue with his superior he was detained, escaped Liberia and made his way to Spain and then Canada.

Upon arriving in Canada, he was flagged almost immediately by immigration officials, who intervened in his refugee case, arguing that as a member of the Liberian military from 1992 to 2001, he was complicit in war crimes.

The case went to the Immigration and Refugee Board in 2004. After hearing “considerable” evidence, the government abandoned its war crimes case against Horrace, documents show, saying there was no evidence linking him to abuses and that it accepted he had only been an army chaplain.

But the refugee board didn’t buy it.

In her Sept. 16, 2005 decision, refugee judge Ana Costa called Horrace’s statements a “labyrinth of confusing testimony” with “multiple contradictions,” but found what she said was a “curious pattern” to his accounts of his life.

“They largely favoured a revised version of the facts which centred on distancing the claimant from combat, active duty and leadership roles within the army,” she wrote in her decision.

She noted that while he claimed to have been an army chaplain, he had no religious training beyond a Methodist upbringing, but she said it ultimately didn’t matter if he was a padre or a dishwasher.

“The facts before the panel are that while on army duty, the claimant knew that children were being recruited and sent into combat. He not only knew about this, he also aided in preparing them for this task, while failing to speak out against such practices,” Costa wrote.

“The panel finds that the claimant was complicit in his army’s recruitment and active engagement of 13-year-old children into combat.”

She ordered him excluded from making a refugee claim.

For the next 15 years, Horrace’s case continued on a slow journey through the Federal Court, the Immigration and Refugee Board, the Canada Border Services Agency, and Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

According to his court file, Horrace went to the Federal Court to have the refugee board decision overturned, denying he had recruited child soldiers and maintaining he was just an army chaplain who was never involved in combat or even saw the front lines.

“I want to clear my name,” he wrote in 2006.

As a result, a second refugee board hearing was held and his claim was rejected in 2008. He appealed again to the Federal Court and lost in 2009.

Next, he applied to stay in Canada on humanitarian and compassionate grounds, arguing that he had a Canadian wife and children.

He then asked for a risk assessment, which considers whether it is unsafe to deport someone, but in 2011 officials found he could be sent back to Liberia without any problem.

Meanwhile, he complained to the court about what he called a “false newspaper article” in Maclean’s magazine that identified him as a war crimes suspect. He alleged the report had “held up” the processing of his immigration application.

In 2013, Horrace was charged by Woodstock, Ont., police with theft over $5,000, making counterfeit money and fraud. That same year, he went to the Federal Court for a third time in an attempt to force the government to give him permanent residence.

The government’s response, filed in 2015, said he was still under investigation and that “given the serious allegations that the applicant forcibly conscripted children and committed rape and murder,” the delay in processing his case was not unreasonable.

The court ruled against Horrace once again.

When he was killed, he was five months into his fourth appeal to the Federal Court. He wanted the court to order the government of Canada to give him permanent residence.

He said he had received a conditional discharge for his criminal charges and the government had not presented any evidence the war crimes allegations he had faced had “any factual basis.”

“Mr. Horrace strenuously denied the allegations that he was involved in the atrocities that occurred in Liberia. He fully cooperated with Canadian authorities throughout a decade-long security investigation,” his lawyer Meghan Wilson said.

“This investigation never yielded evidence that would justify legal action being taken against him,” she said. “He had lived peacefully in Canada for almost 20 years. It is very painful for his family to see these allegations spread in the media.”

Prof. Sundberg said it was “crazy” that someone could live freely in Canada for so long despite having failed at every step of the immigration process and being suspected of war crimes.

“We need to have a wholesale review of our legislation, our regulations and our legal processes, so that we don’t have individuals who are war criminals, people who have trafficked in child soldiers, who have committed horrific war crimes abroad, come here, fail a refugee claim, are ordered removed and remain for decades after,” he said.

According to his immigration files, Horrace was the co-owner of Ann’s Touch Salon in Toronto and attended Sunday mass at Rhema Christian Ministries. He was a Salvation Army volunteer and studied to be a pastor.

On June 21, four suspects arrived at his London, Ont., home in two vehicles at 4:40 a.m. and forced their way inside, police said. A “physical altercation occurred which culminated with the victim being shot by one of the suspects.”

After responding to a 911 call, police found the victim with a gunshot wound. Paramedics took him to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead. The suspects involved fled before police got to the scene.

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.