Several scientists say the publicly-available COVID-19 data from Canada’s public health agency is “incomplete” and hurts their ability to build accurate pandemic models and forecasts that can help inform decision-makers.

They argue they need better data “urgently” and Canada as a whole needs a more robust and standardized system for data collection and sharing between the provinces and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

“It’s not about whether I get to write a paper with a model in it,” said Caroline Colijn, an infectious disease modeller and mathematics professor at Simon Fraser University.

“It’s about whether we can answer the key questions we need to be able to answer nationally about how do we relax distancing? How do we monitor so we know what’s going on if we did start to relax distancing measures? How can we safely restart our economy?”

Colijn and Amir Attaran, a professor of both law and public health at the University of Ottawa, are both scientists trying to model the novel coronavirus pandemic in Canada.

High quality, detailed data can help scientists form a clearer picture of what’s happening in what areas of the country and make suggestions about what each province or territory should be doing next, they said.

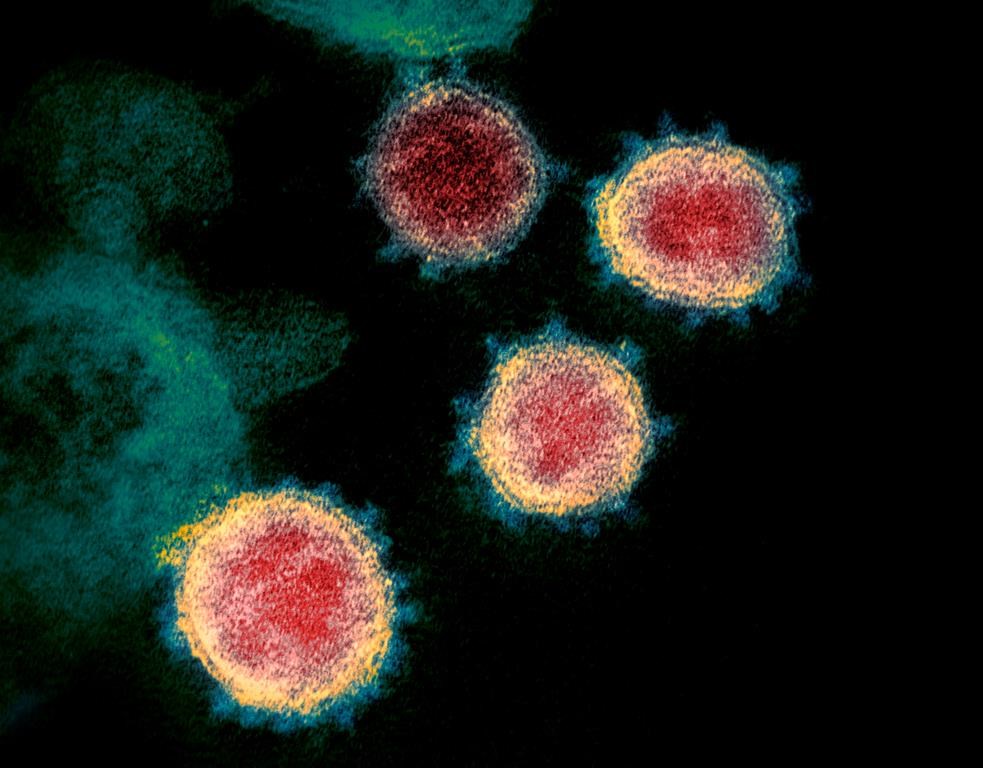

But the data about confirmed cases of COVID-19 — the disease caused by the new coronavirus — that PHAC has thrown online has some serious holes, they say.

In an interview with Global News, Attaran said there’s only about 14,000 confirmed Canadian cases included in the dataset, fewer than half the cases that PHAC is reporting across the country.

The data also isn’t separated out geographically. This makes the dataset “almost completely useless,” Colijn argued, because the epidemic broke out in different provinces at different times and the provinces have been testing different base populations.

The dataset also doesn’t specify whether the “episode date” listed for a single case is the date when someone’s symptoms first appeared, the laboratory testing date or the date a case was reported to an authority — dates that “can differ by weeks,” the B.C. researcher said.

Get weekly health news

Attaran raised the issue of COVID-19 data before the House of Commons health committee on Tuesday, telling MPs studying Canada’s response to the pandemic that “scientists inside and outside government only have an incomplete data picture to work with.”

“With one eye gouged out, they can’t churn out the best possible epidemiological forecast, meaning that we as Canada bumble into this end game unfit and unready,” he said.

Attaran accused PHAC of deliberately hiding some COVID-19 data, suggesting the agency must have raw geographic data, for example, if it’s mapping out cases by province on their website.

Global News contacted PHAC for comment but did not receive a response by deadline.

On its epidemiological daily summary for April 16, PHAC said it had received “detailed” case data for 18,321 cases, or 63 per cent of reported cases. The summary notes that data on these cases are “preliminary” and provinces and territories “may not routinely update detailed data.”

Better cross-Canada strategy needed, scientists argue

Attaran and Colijn both think systemic issues with how public health data is “siloed” and shared in Canada is ultimately to blame for the limited data to which they’ve had access as the coronavirus spreads.

PHAC relies on the provinces to pass along their data but the provinces aren’t all tracking COVID-19 data in the same way, Colijn told Global News.

For example, information on who is being tested for the virus and why — for both positive and negative cases — isn’t being collected in “a consistent manner” across the provincial health systems and by their respective regional health authorities, she said.

“I think we’re almost no better off modelling Canadian populations here in Canada than we would be if we were sitting with an Internet connection literally anywhere in the world looking at publicly available data,” said Colijn, who holds a Canada 150 research chair in mathematics for evolution, infection and public health.

“I think that’s really shocking for Canada, because I think we should be able to do this.”

Pressures and concerns about privacy also present another hurdle when it comes to sharing and disclosing data in urgent situations, scientists argued.

“There’s no question that effective mechanisms can be set up that prevent breaches of privacy while still allowing data scientists to use their skills and insights to improve every aspect of healthcare and many other key services,” David Naylor, a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said in an email to Global News.

For his part, Attaran thinks it’s a major problem that provinces aren’t obligated by law to share their public health and infection disease surveillance data and he urged MPs on Tuesday to push for legislated data sharing.

But he fears politicians won’t go that route because the provinces “have insisted they control their own data” and forcing them to share it might be “politically sensitive,” he said.

An information sharing agreement does exist between the federal government and the provinces and territories, he told Global News, but he argued it has no “teeth.”

“There’s no reason” why Canada can’t have a data system where the provinces input their case data regularly and have it “automatically passed on to a larger federal database,” he said.

“I think a reasonable solution would be that when there’s an epidemic emergency, the province shall deliver any data on active cases to the federal government within 24 hours … and it shall deliver it in such a way that permission is given to the federal government to make it public and make use of it.

“We should have transparency over data and epidemic outbreaks.”

While she had no comment on legislation specifically, Colijn said “it’s really important to have a good national strategy and to have data sharing and data collection be part of that national strategy.”

“Building up that understanding and then introducing an appropriate pandemic plan and actually implementing that plan and having data be part of that, I think that could be incredibly valuable,” she said.

“It could be that legislation from MPs would would really help with that.”

The Prime Minister’s Office and the federal health minister’s office did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Legislation or no legislation, Colijn said it’s not too late in the current pandemic to get more complete data.

“It is not beyond us to make a detailed line list where we write down information about each case and their timings in a high-density way,” she said.

“We could do this if we wanted to do it.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.