Overheard on British radio: a customer had this conversation with a shop assistant.

“Do you have any crucifixes?”

“Which kind? We have the plain ones and the ones with the little man on it.”

Had this exchange occurred around 40 AD, it would be understandable. Biblical scholars tell us that Jesus didn’t begin to become famous, at least beyond the places where he lived, until decades after the crucifixion. And thus ends my awkward Easter-themed way of leading into this list of musicians who didn’t achieve the fame they deserved until after they died.

1. Robert Johnson (died Aug. 8, 1938, age 27)

After failing to impress as a guitarist — he was terrible, if we’re honest — Johnson disappeared for a while to practise. When he turned up again, he’d become miraculously good, thereby sowing the seeds of Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for guitar virtuosity. From 1932 to 1938, he was an itinerant musician, mostly sticking close to the Mississippi Delta but also travelling as far as Chicago, New York, and even up into Canada. He played juke joints, dances, and street corners.

Johnson didn’t leave behind a lot of recordings. There were sessions Nov. 23-25, 1936, in room 41 of the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas. More recording sessions were held in Dallas on June 19-20, 1937, for the Brunswick Record Corp.

A year later, he was dead, found by the side of the road near Greenwood, Miss. Was it poison by a rival? Congenital syphilis? No one knows.

Johnson remained a virtual unknown until 1961 when Columbia Records released a compilation of those recordings on an album entitled King of the Delta Blues Singers. That record brought him to the attention of blues players and nascent rockers like Eric Clapton and Keith Richards. A legend was born 23 years after his death.

2. Otis Redding (died Dec. 10, 1967, age 26)

Redding is now widely considered to be one of the greatest singers ever produced by America, and a massive influence on R&B and soul music. But outside of a small group of fans, Redding was mostly unknown, restricted to playing small gigs in the U.S. South.

There were a few early singles starting in 1962 and a debut album entitled Pain in My Heart via Stax Records that saw him tour across America as well as to London and Paris, but none of his songs bothered the top 20 singles charts.

In August 1967, he was sitting with Steve Cropper, the guitarist for Booker T & the MGs, who served as the Stax house band. Redding had rented a houseboat that was docked at Waldo Point near Sausalito, Calif. It was there they cobbled together a song originally called Dock of the Bay using lyrics Redding had scribbled on a bunch of napkins and hotel stationary.

The song was recorded twice, with the final version committed to tape on Nov. 22, 1967, at Stax Studios in Memphis. Some overdubs were added on Dec. 7. Three days later, his Beechcraft H18 airplane went down in bad weather in Lake Moana on its way from Cleveland to a gig in Madison, Wisc. Redding was not among the survivors.

Cropper quickly remixed the song, adding the seagulls and the ocean sounds, and had the single in stores by Jan. 8, 1968. Now called (Sittin’ on the) Dock of the Bay, the song became the first-ever posthumous record to reach number one on the Billboard charts. It immediately sold more than four million copies, and resulted in people discovering Redding’s genius.

READ MORE: Radiohead posting weekly concert movies to YouTube during coronavirus pandemic

3. Jim Croce (died Sept. 20, 1973, age 30)

After two unsuccessful solo albums, Croce turned to a series of part-time construction gigs as a welder in Philadelphia to survive. During his spare time, he continued to write, record, and play the occasional gig. Things finally turned around with his third album, You Don’t Mess Around with Jim, which he was moved to record when he discovered that he was going to be a father.

The record did reasonably well. He started to get radio airplay with songs like Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels) and Time in a Bottle which landed him appearances on both The Tonight Show and American Bandstand. Still, gigs were mostly in coffeehouses, on college campuses, and the occasional folk festival, though he did manage to get to Europe at least once.

Finally, on July 19, 1973, he got what he wanted: a number one single for Bad Bad Leroy Brown. But Croce was disillusioned. He was deeply in debt to his record company as the result of some huge advances. He told his wife in a letter that he was quitting the music business and coming home to concentrate on writing short stories and maybe some movie screenplays. The letter made it home. He did not.

On Sept. 20, 1973, Croce and five other people were killed when their Beechcraft E18 (the same kind of plane that carried Otis Redding to his death) crashed into a pecan tree shortly after takeoff in Louisiana.

Croce’s fame exploded after his death. On Dec. 1, 1973, an album called I Got a Name was released, reaching number two on the charts and resulting in several hit singles. A greatest hits album issued in 1974 went multi-platinum. There have been almost half a dozen more posthumous releases long with video collections of Croce’s TV performances. His music can still be heard in movies ranging from The Hangover Part II, Django Unchained, and X-Men: Days of Future Past.

This song was released on Sept. 21, 1973, less than 24 hours after Croce died.

4. Nick Drake (died Nov. 25, 1974, age 26)

Get breaking National news

A brilliant but moody and depressed songwriter from the era of classic British folk, almost no one noticed any of his three albums, Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971) and Pink Moon (1972). As he was getting ready to make his fourth album, his mental state took a turn for the worse.

Existing only on a £20-a-week retainer from Island Records, he lived in poverty, unable to buy new clothes. He’d also disappear for days at a time, driving his mother’s car aimlessly until he ran out of gas and had to call for a lift. He grew withdrawn often and refused to wash his hair or tend to other hygienic matters. He’d never really recovered from a nervous breakdown in 1972 which saw him hospitalized for five weeks for depression. One doctor believed he might have been schizophrenic.

Early on Nov. 25, 1974, after his meagre weekly retainer had expired, he took an overdose of an antidepressant called amitriptyline at his parents’ home where he was living. He was found dead by his mother that morning.

Drake seemed to be destined to fade into history. Island didn’t bother with any posthumous releases until 1979. But by the early ’80s, several big stars, including Robert Smith of The Cure, Kate Bush of REM, and Paul Weller, began to drop Drake’s name as an influence. Fans started showing up on his parents’ lawn. And then came the Volkswagen commercial in 1999.

People were entranced by the nearly 30-year-old song in the spot. Drake’s album sales spiked exponentially. Users of this new thing called Napster started looking for more of his music. Music supervisors began sifting through Drake’s catalogue for use in movies and TV shows. Within a few years, Drake had sold several million albums, far, far exceeding anything he managed to sell while he was alive. And today, guitarists study his odd tunings and innovative use of chord structures.

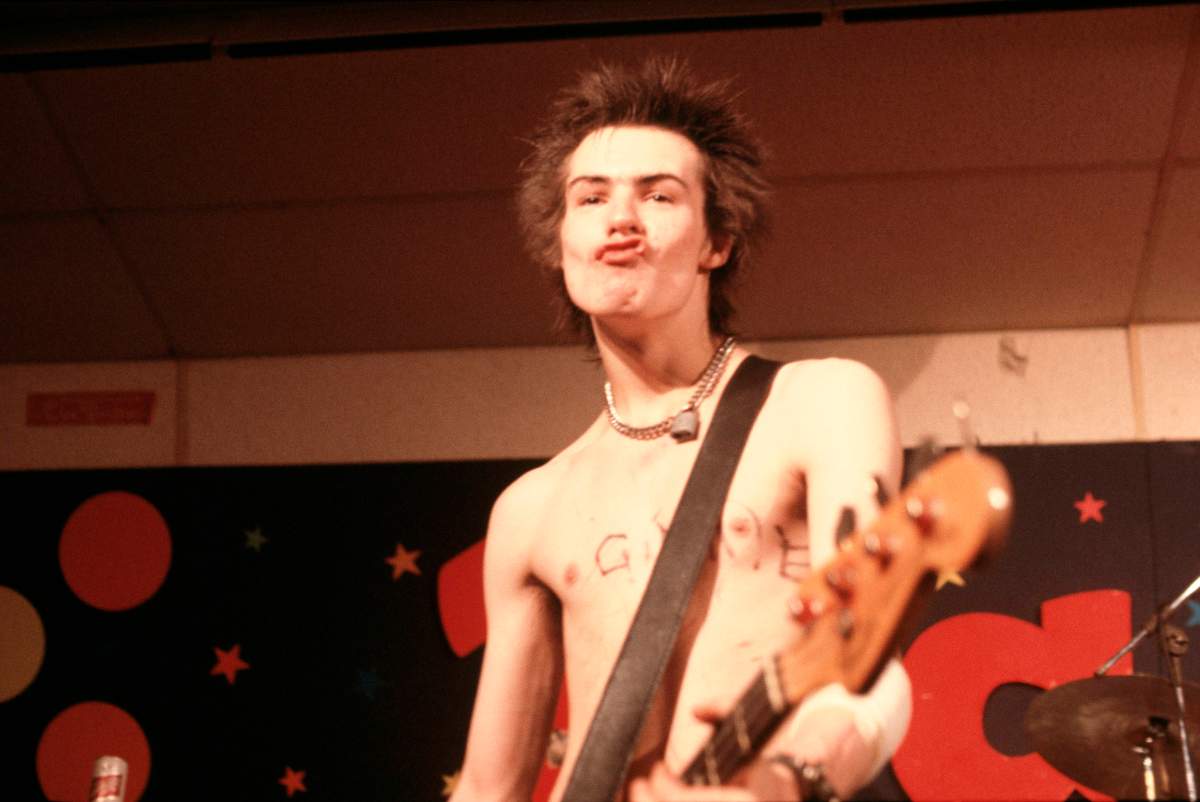

5. Sid Vicious (died Feb. 2, 1979, age 21)

John Simon Ritchie was a total screw-up. He was into drugs, violence, and punk rock. To Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren, that made him the perfect replacement for bass player Glen Matlock. So what if he couldn’t play bass? All that mattered was that he looked and acted the part.

Vicious’ time with the Sex Pistols was a disaster. On the band’s one-and-only American tour, he was so obnoxious that he managed to get himself beaten up by his own bodyguard. On the way back to England after the Pistols’ final show in San Francisco in January 1978, he overdosed and had to stop in New York. That’s when he decided to stay put, living with his girlfriend Nancy Spungen in Room 101 of the Chelsea Hotel.

Sid formed a band called The Vicious White Kids and played a few gigs and made a few recordings. But then on Oct. 12, 1978, Sid awoke from a druggy haze to find that Nancy had been stabbed to death in their hotel room. He was arrested, charged with her murder, and sent to Riker’s Island where he managed to go through both a horrible detox and several beatings at the hands of other inmates.

Released on bail, Vicious, his mom, a new girlfriend named Michelle Robinson, and an assorted mixture of friends, met at an apartment at 63 Bank St., New York, for a celebratory spaghetti dinner on Feb. 1, 1979. That night, Sid somehow managed to acquire some heroin (accounts vary on how he did it) and by morning, he was dead of an overdose.

At the time of his death, Sid was a punk rock curiosity, a burnout who met an inevitable end. But as the years passed, the Sex Pistols became recognized as one of the most revolutionary and disruptive bands of all time. Infamy turned into fame. Sid’s ignominious death turned him into an anti-hero, celebrated in books, movies, compilation albums, and millions of T-shirts. Now the name “Sid Vicious” and the pairing of “Sid and Nancy” is shorthand for certain types of self-destructive lifestyles.

READ MORE: Self-isolating Ontario family recreates entire ‘Simpsons’ opening at home

6. Ian Curtis (died May 18, 1980, age 23)

During their short existence, Manchester’s Joy Division attracted small but devoted crowds of disaffected youth, some wearing plain brown raincoats as a uniform. And while the band was undeniably brilliant, the money just wasn’t coming in.

Curtis, beset by a worsening case of epilepsy, a drug-and-alcohol issue, a broken marriage, a young daughter, and an affair with a Belgian fan, was ill-equipped to handle the pressure. Unable to carry on any more, he put an Iggy Pop album on the stereo and died by suicide in his house at 77 Barton the Salford area of Greater Manchester. The very next day, Joy Division was supposed to leave for a North American tour, a road-trip that could have changed everything for them.

Joy Division only managed to release one proper album while Ian was alive, 1979’s Unknown Pleasures. A second album, Closer, was released two months to the day after Ian’s death.

While the three remaining members of the band regrouped and continued as New Order, Joy Division slowly emerged from obscurity into a powerful force whose influence was taken up by everyone from U2 and Radiohead to The Smashing Pumpkins and Interpol. Both Unknown Pleasures and Closer are considered to be essential parts of the post-punk canon.

Meanwhile, the story of Curtis and the band have been told with CD compilations, box sets, books and numerous movies and documentaries. There was even a movement to turn the house at 77 Barton into a Joy Division museum.

7. Hillel Slovak (died June 25,1988, age 26)

Hillel was part of the gang of students at Fairfax High School in Hollywood who would later form the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Using a guitar he got for his bar mitzvah, he and his mate Anthony Kiedis (along with his friend Michael “Flea” Balzary) messed around with music, played the odd gig, and took a bunch of drugs.

After drifting through a bunch of bands, Slovak, Kiedis and Flea created their own band called Defunkt, which evolved into Tony Flow and the Miraculously Majestic Masters of Mayhem. That was too long to fit on a gig poster, so they became the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The band did OK on a local level, enough to secure them a contract with EMI Records. Long, long story short, Hillel worked with Peppers through their first three albums and on EP, none of which elevated the band above cult status. What money was earned went to drugs.

Then Hillel died of a heroin overdose. Police believe his body lay in his apartment for a couple of days before he was found.

There was much doubt that the band could continue without Slovak and drummer Jack Irons, who left because he couldn’t deal with what had happened. But Kiedis and Flea regrouped using guitarist John Frusciante and drummer Chad Smith. Since then, they’ve sold tens of millions of albums. Hillel is remembered fondly as a founding member of the group.

8. Eva Cassidy (died Nov. 2, 1996)

Though hugely talented as an interpreter of jazz and blues, Cassidy was an unknown outside of Washington, D.C. Then, in 1993, she was diagnosed with melanoma after a mole was removed from her back. Three years later, she felt some pain in her hips. X-rays revealed that the cancer had spread to her bones and lungs. Although she went through very aggressive chemo treatments, she died later that year at the age of 33.

Then a strange thing happened.

Two years after Eva’s death, the BBC started playing a couple of her songs. There was a scramble to find any live performance footage. A compilation album entitled Songbird was released in 1998, reaching the upper heights of the British charts. That led to a series of posthumous releases, three of which reached number one in the U.K. (total sales <10 million copies) and one number one single. She also had top 10 albums in Germany, Norway, Sweden and Australia. There are also plans to make a movie based on her life.

9. Jeff Buckley (died May 29, 1997, age 30)

The son of folky Tim Buckley, Jeff worked as a session musician in L.A. while also writing his own music. In the early ’90s, his father’s old manager (Tim died of a heroin overdose in 1975 when Jeff was just nine), brought him to New York for a series of showcases. The result was a record deal with Columbia, which issued the Grace album in 1994.

At first, Grace was a hard sell. It was a very good record, but outside of a cadre of early fans, Buckley was having a hard time gaining traction, despite spending close to three years on the road promoting the album. Still, Columbia wanted a second album, so Jeff moved to Memphis to work on music. He’d planned to call the album My Sweetheart the Drunk.

On the night of May 29, 1997, Jeff decided to wade into Wolf River Harbor, a channel of the Mississippi River. Fully clothed and already weighed down, he was caught in the wake of a passing boat and was pulled under. His body was found five days later. An autopsy ruled that he died of an accidental drowning.

As the news of Buckley’s death spread, interest in the Grace album picked up considerably. Material for that second album was released under the title Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk. Documentaries followed on the BBC and French television. Artists ranging from Chris Cornell to PJ Harvey sang his praises. Songs were written about the premature death of the man with the sweet voice.

In 2008, Buckley’s version of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah sold nearly 200,000 copies in a single week after the song was featured on American Idol. It reached number one on the iTunes download chart.

10. Bradley Nowell (died May 25, 1998)

So many things were going right for Bradley Nowell in the spring of 1996. After slogging it out with his band Sublime, the band was poised to break things wide open with the release of their third album, an affair entitled Killin’ It that was perfectly in line with the ska-punk that was emerging in Southern California. It was going to be a good year.

But not everything was working out. Nowell had a deepening relationship with heroin. After getting married to the mother of his 11-month-old son on May 18, 1996, he was hoping to get off the junk. But a week later, as Sublime was on a five-day tour through the northern part of the state, he was found on the floor of his room at the Ocean View Motel in San Francisco. His dog, a dalmatian named Lou Dog, was curled up and whimpering on the bed. Nowell had died of a heroin overdose.

That third album was released on July 30, now with the title Sublime. As the months went by, sales got stronger and stronger, reaching the top 20 of the Billboard album charts and producing at least three alt-rock radio hits. The band was all over MTV. By the end of 1997, Sublime had sold more than six million copies in the U.S. alone.

Then came a series of posthumous releases through 1997 and 1998. A box set was issued in 2006. At last count, Sublime has sold more than 17 million albums worldwide.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with 102.1 the Edge and Q107 and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play.

Comments