By the time he was 18, Ian Stedman had visited his family doctor more than 180 times.

That’s not even counting referrals to specialists, extra testing or visits to walk-in clinics and emergency rooms, of which there were many.

He could be anywhere — in math class, at the grocery store with his mom or just sitting at home — when a bright red rash would take over his entire body, his eyes would turn red, his joints would ache and his head would pound.

The symptoms would come on suddenly and seemingly without cause.

“For the red eyes, I’d be given drops. For the arthritis and headaches, I’d be given anti-inflammatory medication,” Stedman said. “The diagnosis was always broad strokes … They would throw different medicines at it and nothing would work.

“The story of most rare disease patients who don’t have a diagnosis is that [doctors] would just treat the symptoms.”

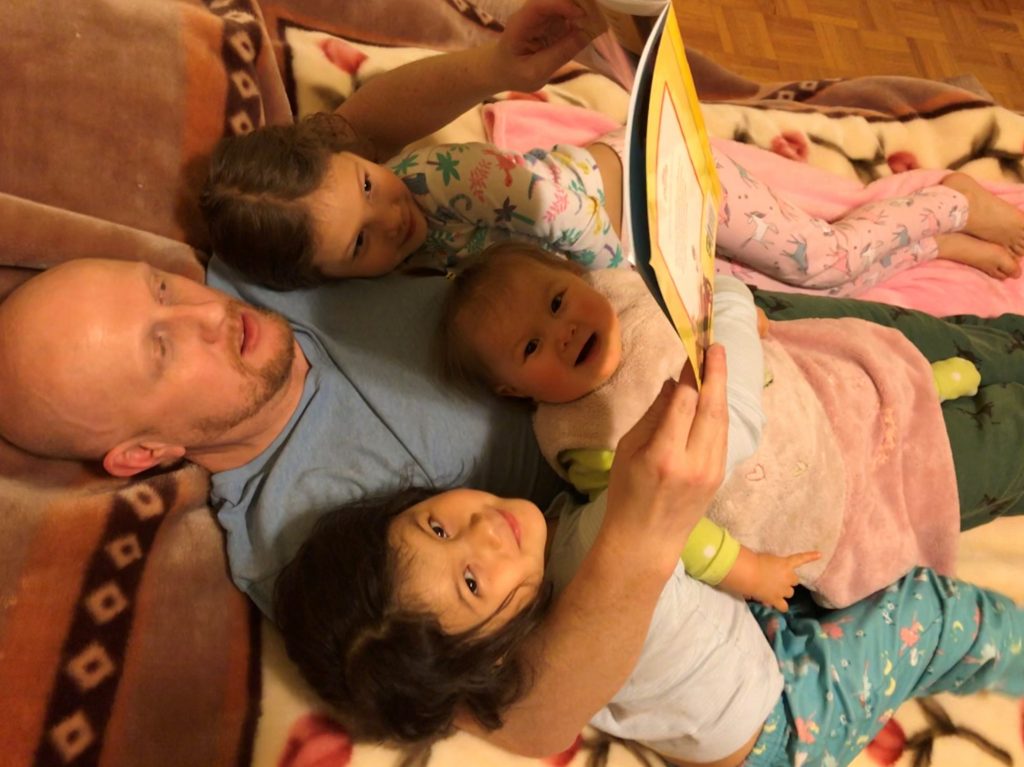

It wasn’t until Stedman was 30 years old — when his first child was born with the same full-body rash — that he realized something more serious was going on.

“Babies have rashes, so everyone kind of dismissed it for a while,” the Vaughan, Ont., resident said. “But then I took paternity leave … from month nine to 12 of her life and I started to see that the rash was the same as mine.”

Then his daughter stopped walking, and Stedman made it his mission to find out what was going on. He conducted extensive independent research and he made himself a “guinea pig” for doctors, determined to prove that he and his daughter were suffering from the same thing.

In 2013, Stedman, his daughter and his mother were all diagnosed with an extremely rare disease known as Muckle-Wells syndrome, a genetic mutation causing an overproduction of a protein complex responsible for regulating inflammation. Left untreated, it can be fatal.

Unfortunately, Stedman’s gruelling decades-long experience isn’t unique.

One in 12 Canadians are affected by a rare disease, according to the Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD).

The central problem presented by rare diseases is that they’re rare, said Wong-Reiger.

Get weekly health news

Each disease affects only a small number of individuals across the country and around the world, and this often leads to a lack of understanding and treatment options, leaving patients with more questions than answers.

Rare diseases in Canada

A rare disease is defined as affecting fewer than one person in 2,000 in their lifetime, according to CORD, and there are more than 7,000 currently known to the medical community. Dozens more rare diseases are discovered each year.

About 80 per cent of rare diseases are caused by genetic changes, and 25 per cent of children with a rare disease won’t live to 10 years old.

Each rare disease is uniquely different, said SickKids Hospital senior scientist of genetics and genome biology Michael Brudno, and there can even be variation in how a disease presents in people with the same diagnosis.

“This could be a new change — something that happened in your genome as you inherited it from your parents — and you end up with a mutation that causes this disease.”

The other way a person can develop a rare disease is if each parent has “one bad copy” of a gene.

“We have two copies of every single gene. If you have one bad copy, that’s OK, but if one parent has one bad copy and the other parent also has a bad copy, then you can get two copies and you will end up with the disease,” he said.

The biggest issue presented by rare diseases is getting a diagnosis.

“The journey starts not with the diagnosis, but with the diagnostic odyssey, which is a term used for the fact that there are individuals who have had incorrect diagnoses for years before getting them an accurate diagnosis and any kind of treatment,” said Brudno.

“Until you have a diagnosis, you have nothing.”

Barriers to access

Stedman, who works as a lawyer and ethicist, saw firsthand the importance of advocating for oneself throughout the rare disease journey. It was because of his persistence that he was able to secure a diagnosis and treatment for himself, his mom and his daughter.

However, he’s also acutely aware of how many people aren’t as privileged, and how easy it would be to get lost in the system without the same experiences he has.

Wong-Reiger has seen these barriers to access at play in her work with CORD.

“There are huge barriers,” said Wong-Reiger. “Some of them … are cultural, some of them are just a lack of understanding and awareness.

“It’s very easy to get dismissed.”

For example, it is more difficult for a newcomer to Canada who doesn’t speak English to articulate the issues they’re having, further delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Cultural biases have been seen to prevent diagnosis and treatment, too.

“I’ve had a father say … ‘I can’t get my daughter diagnosed because nobody will ever marry her,'” said Wong-Reiger.

Issues can also arise when someone from a unique demographic contracts a disease typically associated with another country.

“An interesting example is thalassemia,” said Wong-Reiger.

“Originally it was found in Greece, so most of those populations are well taken care of here in Canada … but now, the same disease is coming in from eastern Asia, and a lot of those people get missed. They don’t get the same level of attention and support.”

Ultimately, more education and awareness is required.

“Even when there are tests and services and treatments available, a lot of times you don’t get access to them because of cultural, language or religious barriers,” she said.

Raising awareness

In her work with CORD, Wong-Reiger hopes to improve the lives of people with rare diseases.

“That would include stimulating research in various diseases … supporting clinical excellence and improving diagnosis times,” she said.

She believes more education and awareness are the next steps to helping people with rare diseases.

“It’s funny when you talk about people not knowing any rare diseases because, when we press it, everybody knows somebody,” said Wong-Reiger.

“We want to make sure that people with rare diseases have the same kind of care and treatment as people with more common conditions.”

This means investing more in education and awareness — even in health professionals.

Stedman hopes Rare Disease Day will stoke conversation about rare diseases and the immense physical and mental toll they can take.

“A lot of people get lost in the system,” he said.

Meghan.Collie@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.