More than a third of the world’s poorest countries are suffering from the highest rates of both undernutrition and obesity, according to a newly published report.

The report, published in the journal The Lancet, said the problem is being caused by the increasing availability of “ultra-processed” foods and beverages and major reductions in physical activity.

The world is now “facing a new nutrition reality” where individuals across countries are facing both undernutrition and obesity at different points in their life, said Francesco Branca, director of the World Health Organization’s Department of Nutrition for Health and Development and lead author of the report.

“We’ve really noticed the nutrition situation is changing in the world, and then we have the epidemic of obesity, which is expanding very quickly in these low-income countries,” said Branca.

“But at the same time, we haven’t seen the reduction in the undernutrition — the stunting and wasting — we were expecting, and so now more and more countries with lower-middle income have these two conditions simultaneously.”

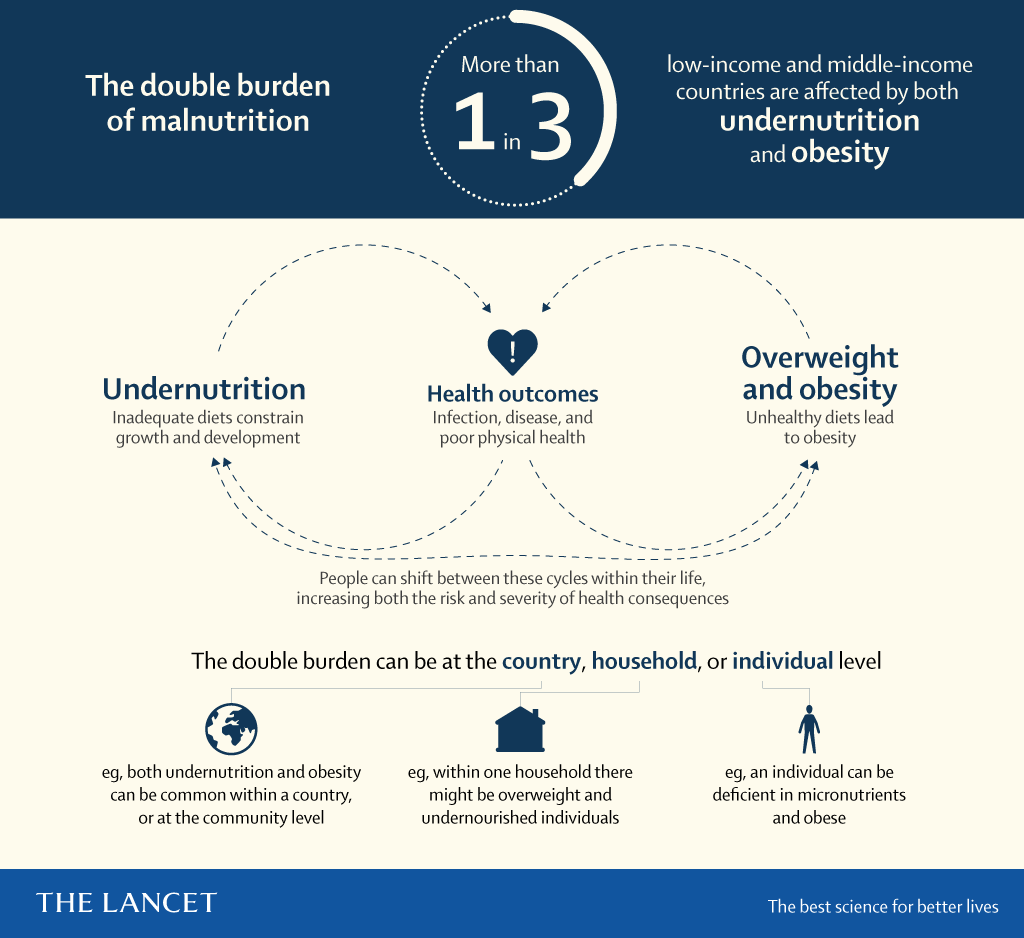

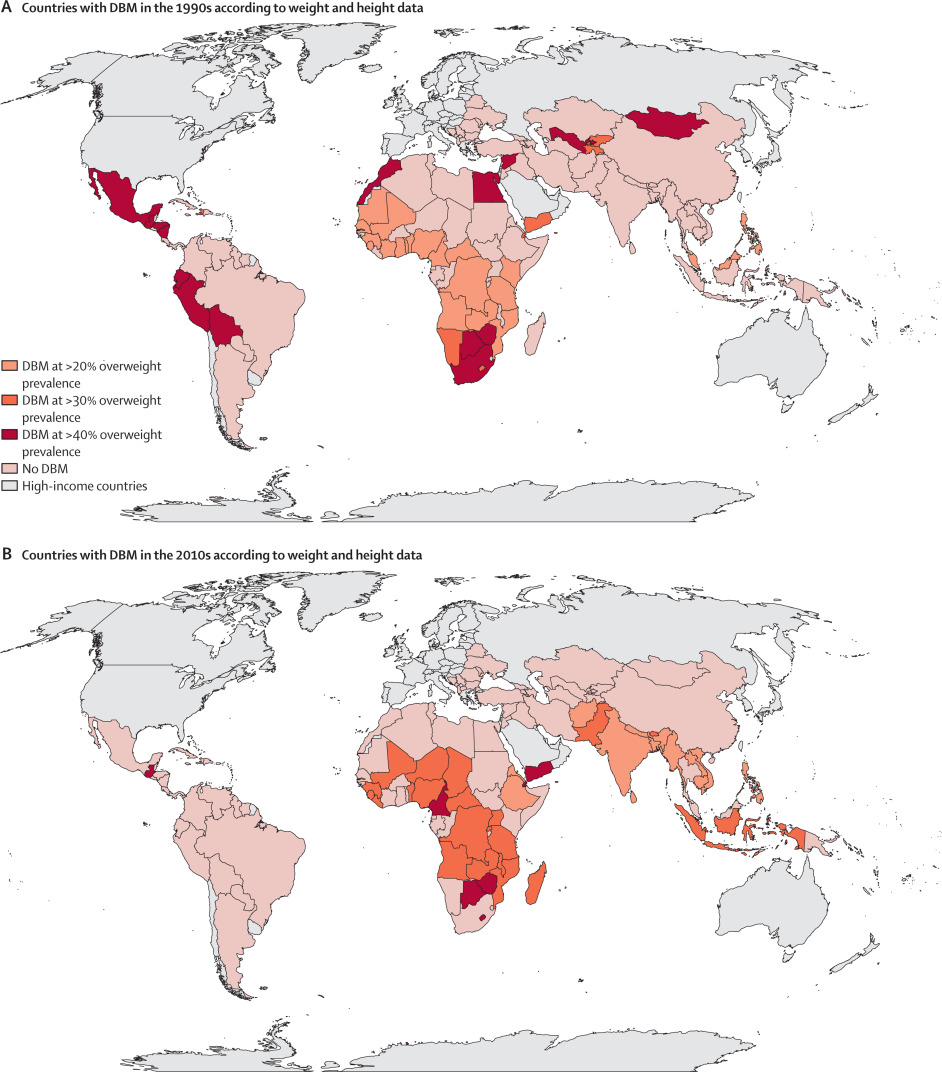

The report calls the trend the “double burden of malnutrition,” and found that it affected 45 out of 123 countries in the 1990s, rising to 48 out of 126 countries in the 2010s.

With more than 150 million children with stunted growth and 2.3 billion overweight people globally, according to estimates, the researchers say there is an overlap of severe malnutrition conditions from the individual level to the community level.

Branca used survey data from the world’s poorest countries to classify the countries with the double burden, with the criteria being that a country had to have 15 per cent of its population “wasting” (having a lower than average weight for one’s height); more than 30 per cent of its children aged 0-4 years “stunting” (having a lower than average height for one’s age); more than a fifth of its women aged 15-49 with “thinness” (having a BMI of less than 18.5) and more than 20 per cent of its population “overweight” (having a BMI above 25.0).

The report also found that about 14 countries with some of the world’s lowest incomes had been developing the double burden since the 1990s, and that fewer wealthier countries still classified as low-middle income had been affected, essentially widening the gap.

The report identifies Indonesia as the largest country with a severe double burden, along with many other Asian and sub-Saharan African countries, in particular.

Get weekly health news

In the last decade, countries like Botswana, Zimbabwe, Yemen and Guatemala were among those with the highest prevalence of the double burden.

According to Branca, one of the common drivers leading to the double burden is a country’s food system not delivering enough healthy food to the population. The increasing ease of access to cheap, unhealthy foods, in particular, caused the trend to manifest, said Branca.

Having both undernutrition and obesity can lead to lasting effects across generations, with the report citing maternal undernutrition and obesity being associated with poor offspring health — a trend that can produce a somewhat cyclical effect.

“We found that there is an intimate biological connection between the undernutrition and the overweight in countries where children are born with low birth weights, or in countries where children develop growth retardation in the first years of life,” said Branca. “Then we have a higher likelihood that those people become then overweight adolescents, and then adults.”

“This is a condition that is transmitted from one generation to the next, and mothers and who are not well-nourished give birth to children who are also with low birth weights, but also may lead to children who have then metabolic disturbances that are going to experience later in life.”

The report also outlines the potential economic cost of the double burden, as its health effects could be translated into lost wages and productivity as well as higher medical expenses in the long-term.

The researchers are calling on nations to implement changes to their food system to address the problem, ranging from increasing the quality of food at its production, to implementing policies to address both the pricing and marketing of foods, to even providing pre-adolescent kids aged four years and older with nutritious meals.

“Continuing with business-as-usual is not fit for purpose in the new nutrition reality,” Corinna Hawkes, a professor from the University of London’s Centre for Food Policy, said in a press release.

“The good news is that there are some powerful opportunities to use the same platforms to address different forms of malnutrition. The time is now to seize these opportunities for ‘double duty action’ to get results.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.