This is the first in a series of stories on temporary emergency room closures in Nova Scotia. To check out the rest of our CODE ZERO series, click here.

On a warm and muggy day in Sheet Harbour, N.S., at the end of July 2014, the normally busy parking lot at the Eastern Shore Memorial Hospital was nearly empty.

The doors to the facility’s emergency room were shut and locked. The entranceway was dark and still.

“If you have an emergency, please call 911,” read a sign on the door.

The hospital’s ER was closed for 80 hours before it finally reopened, the longest single closure in what has become a common occurrence in the province.

As Nova Scotia grapples with a shortage of doctors and nurses, provincial government data analyzed by Global News shows a rise in temporary emergency room closure. Most are unscheduled and can come with as little as half a day’s notice.

Between 2014 and the first three months of 2018, just under half of the emergency rooms in the province — 18 of 37 — were forced to temporarily close, often as a result of a lack of doctors or nurses.

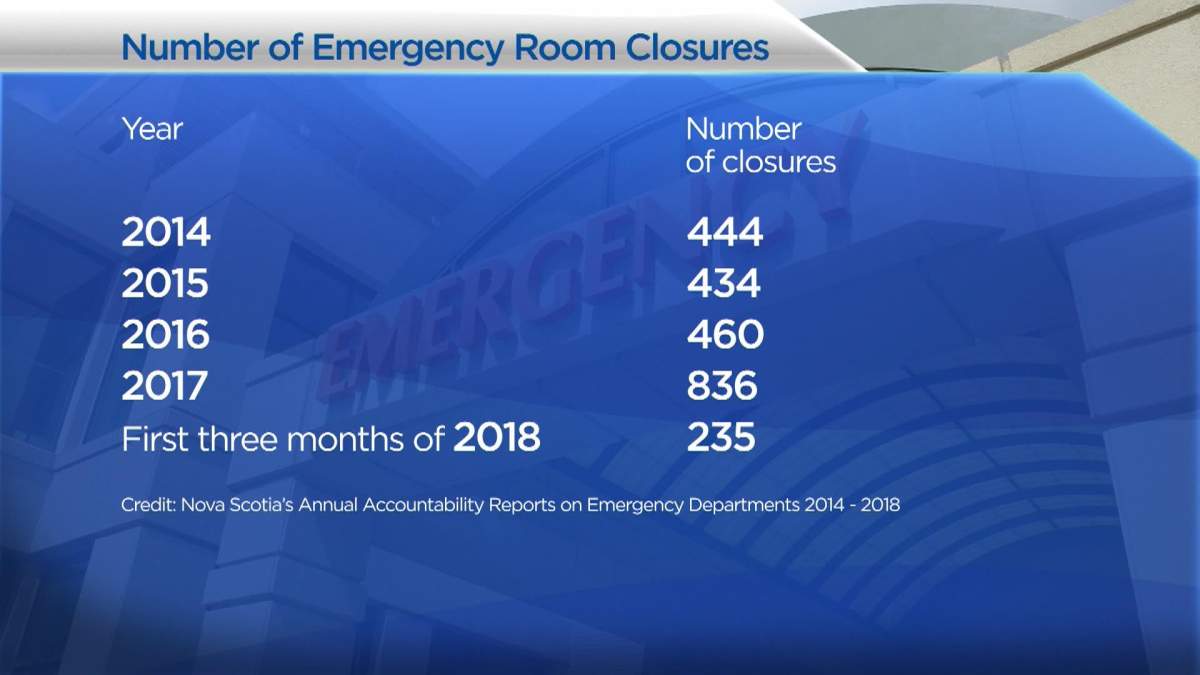

And the number of temporary closures is increasing dramatically, according to data collected from reports prepared by the Nova Scotia government.

READ MORE: Halifax residents rally against Nova Scotia’s health-care ‘crisis’

In 2014, Nova Scotia’s ERs temporarily closed 444 times. By 2017, the number of temporary closures had jumped to 836.

In the first three months of 2018, the most recent publicly available data, there were 253 temporary closures.

If closures continue at the same rate, the province would be on track to set a record with more than 1,000 temporary closures in 2018.

Rural areas experiencing the most closures

Get weekly health news

As Dalhousie University political science professor Katherine Fierlbeck explains, the Nova Scotia government has attempted to balance the limited resources it has with the number of people who need treatment.

The temporary closure of ERs is one of the solutions that has been put in place in the province to manage a shortage of medical personnel. But it comes with risk.

“In a lot of places, we’ll see no major events over the period when something is closed,” said Fierlbeck. “But on the other hand, there might, and this might be something that has to be addressed.”

“The nature of emergency medicine is that you just never know what’s going to happen.”

The results of the analysis by Global News indicate that rural areas of the province are the hardest hit by temporary ER closures.

The Glace Bay Health Care Facility is by far the worst, having experienced 364 closures over the past four years, but it’s slated to be expanded and revitalized as the province moves to reform health care in Cape Breton.

Part of those efforts will see the Northside General Hospital in North Sydney and the New Waterford Consolidated Hospital in New Waterford permanently closed. Beds and resources will be shifted to the Cape Breton Regional Hospital in Sydney and the Glace Bay Health Care Facility.

Fierlbeck says closing emergency centres raises tough political questions.

“The question is exactly … how many centres do we need spread out through the province? … Maybe we should depend upon scale economies and build larger or amalgamate centres so that we have fewer centres,” she said.

Fierlbeck says it’s not surprising that less populated rural areas are taking the brunt of the closures.

But in Shelburne, where the local ER has closed 199 times in four years, or the North Cumberland Memorial Hospital, which has closed 239 times, there is no revitalization project.

The province says it has no plan to shutter facilities in regions outside of Cape Breton.

In contrast to rural Nova Scotia, only 90 of the 2,430 closures that occurred between 2014 and the first three months of 2018 occurred in the Halifax area.

But even the well-staffed locations in that region of the province are becoming susceptible to doctor shortages and ER closures.

In 2017, closures in the Nova Scotia Health Authority’s central zone — which contains the Halifax Regional Municipality — spiked to 55. In the three years before that, the number of closures in the zone had never reached more than 12.

A system in ‘crisis’

The state of Nova Scotia health care — which has been described by protesters, analysts and researchers as a system in “crisis” — didn’t happen overnight.

Provincial politicians agree that there are many causes that brought the province to this point and that those factors vary depending on the region, the policies that have been put in place and the demographics of a specific area.

Experts also agree and say the rapid increase of temporary ER closures is a symptom of a system struggling to cope with a shrinking number of staff.

“Everything is relational, and obviously, you don’t want to drive further than you have to for emergency care. So, basically, it depends on what happens when the emergency room is closed,” Fierlbeck said.

- High blood pressure drug recalled over low blood pressure pill mix-up

- ‘Doesn’t make sense’: Union files labour complaint over federal 4-day in-office mandate

- Canadian Tire ordered to pay nearly $1.3 million for false advertising

- Ottawa gives Canada Post a $1.01-billion loan amid ongoing financial struggles

Comments