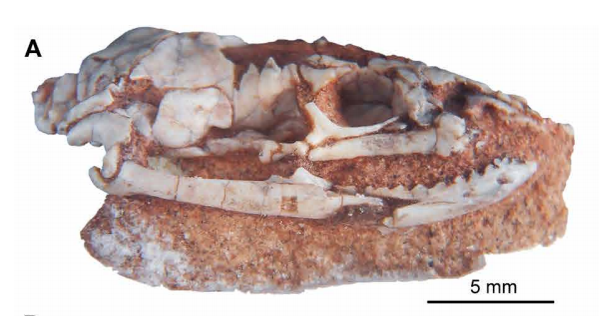

A team of researchers, including an expert from the University of Alberta, say a 100-million-year-old cheekbone fossil found in Argentina is providing critical insight into the evolution of snakes.

The results of the international research were published in a study released Wednesday, show that ancient snakes had a cheekbone — also known as a jugal bone — which may not mean much to many, but to the scientists involved, it reveals a key detail about snake evolution.

“In the past, the fossil record of snakes has been pretty poor,” said Michael Caldwell, a biological science professor and paleontologist based at the University of Alberta. “Lizards have more bones in the cheek region… than a typical modern snake does.

“It makes a difference when you’re tracking the evolution of the ability to eat large prey, if you can accurately follow which bones were lost,” said Caldwell.

The discovery is the culmination of years of research and a collaboration between the University of Alberta and Universidad Maimónides in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

“Our findings support the idea that the ancestors of modern snakes were big-bodied and big-mouthed — instead of small burrowing forms as previously thought,” said Fernando Garberoglio, the Argentina-based lead author for the study.

The bone itself was found by Garberoglio several years ago in the Northern Patagonia region of Argentina. The region itself is a “treasure trove” of snake fossils, so Caldwell, one of the few snake scholars in the world, was called in as an adviser.

Get breaking National news

“I’ve been back and forth to Buenos Aires many times and I’ve brought Fernando here to the University of Alberta probably three or four times… in order to mentor him and work with him on this material,” said Caldwell.

The reason that an Edmonton scientist had to go all the way to Argentina for this discovery is because while Alberta is fossil-rich, snake remains are generally not found in the region.

“Snakes have got lots of tiny vertebra… and very delicate skulls.”

Caldwell said that he was honoured to be involved in the research.

“Being able to reach out and connect with students and science problems around the world… it’s made a complete difference in my professional career,” said Caldwell.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.