Regina, Saskatoon and Moose Jaw, Sask., have some of the highest measured levels of lead-tainted water in Canada.

That’s according to a collection of 2,600 tap water sampling measurements obtained in a year-long investigation by nine universities and media outlets, including Global News, the University of Regina School of Journalism and Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism.

Fifty-eight per cent of the samples in the three cities measured lead levels that were above Health Canada’s recommended limit of five parts per billion (ppb), and the average result was 22 ppb. These samples were primarily taken between 2013 to 2018 in about 450 older homes with lead pipes connecting them to the main municipal water systems.

The Saskatchewan data, released by the three municipalities through freedom of information legislation, was never previously made public and has left some residents wondering why they weren’t told their tap water might be unsafe.

Premier Scott Moe’s Saskatchewan government referred questions about lead in drinking water to a provincial agency that regulates water utility operators. The agency told Global News that it has asked cities to increase their monitoring and efforts to inform the public about the issue.

But the watchdog doesn’t believe that the situation has escalated to a point where it needs to force water utility operators to take more action.

Some residents disagree.

Steve Wolfson and his wife Penny rent a home in Regina’s Cathedral neighbourhood, an area filled with older homes and a history of lead service lines. They care for their nine-year-old twin granddaughters.

Two years ago, they were informed that their home was connected to a water main by an underground city-owned lead service line.

After the City of Regina did testing on Wolfson’s drinking water in July 2017, his results showed some lead levels 10 times higher than Health Canada’s maximum acceptable limit of five parts per billion.

“(The city) made it sound like it wasn’t really terrible, but that it would be good to take precautions,” Wolfson said.

“My concern is beyond our kids — we have young children living on this block. I spoke to a couple of the parents who have these kids, who had no idea that their houses might be getting lead in the water.”

When dissolved in water, lead is colourless, odourless and tasteless, making it impossible to detect without a lab test. According to the World Health Organization, there is no safe level of lead.

Although it can impact anyone, in adults, lead increases the risk of high blood pressure, cardiovascular problems and kidney dysfunction as well as complications during pregnancy.

In children, lead has been linked to behavioural problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and can even result in a loss of IQ points.

“It really is insidious; we don’t see it. We don’t see it unless we test children — although later in life when they start school the teacher and parent might really see that the kid is struggling,” said Bruce Lanphear, a professor of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University.

Last year, Regina started sending out letters, alerting roughly 4,000 residents of city-owned lead service connections.

The city’s sampling results show that 168 homes with lead service lines were tested between 2016 and 2018 and 57 per cent had water samples with lead levels above the federal limit in the first litre out of the tap in the morning, according to documents released through freedom of information legislation.

“Somebody knew some time, a long time ago, that we had all this lead in the water. Whose decision was it not to tell people? Why was it kept secret? Why weren’t we told about this?” Wolfson asked.

“Why was this information not made public a long, long time ago?”

One of Canada’s leading experts on municipal water systems criticized the three cities in Saskatchewan for not being transparent.

“I’m shocked. I’m disappointed. I’m angry,” said Michèle Prévost, a professor of engineering at Polytechnique Montréal, who has advised governments around the world about the issue. “The one thing that’s really missing across Canada is transparency.”

Prévost added that similar results in the U.S. would be made public. “If you want to know in Cincinnati if you have a lead service line and how high your lead is, you type your address, you find it. I don’t understand why the monitoring data is not public.”

Get weekly health news

Comparisons to Flint, Mich.

Flint, Mich., made international headlines in 2015 after elevated levels of lead were found in residents’ tap water. The crisis followed a decision to draw water from a more corrosive source into an aging lead pipe infrastructure. The result was a public health storm, highlighting not just lead-tainted drinking water but the death of 12 people from a Legionnaire’s outbreak as bacteria spread through the water system.

Canadian cities have a variety of scenarios underlying their lead problems.

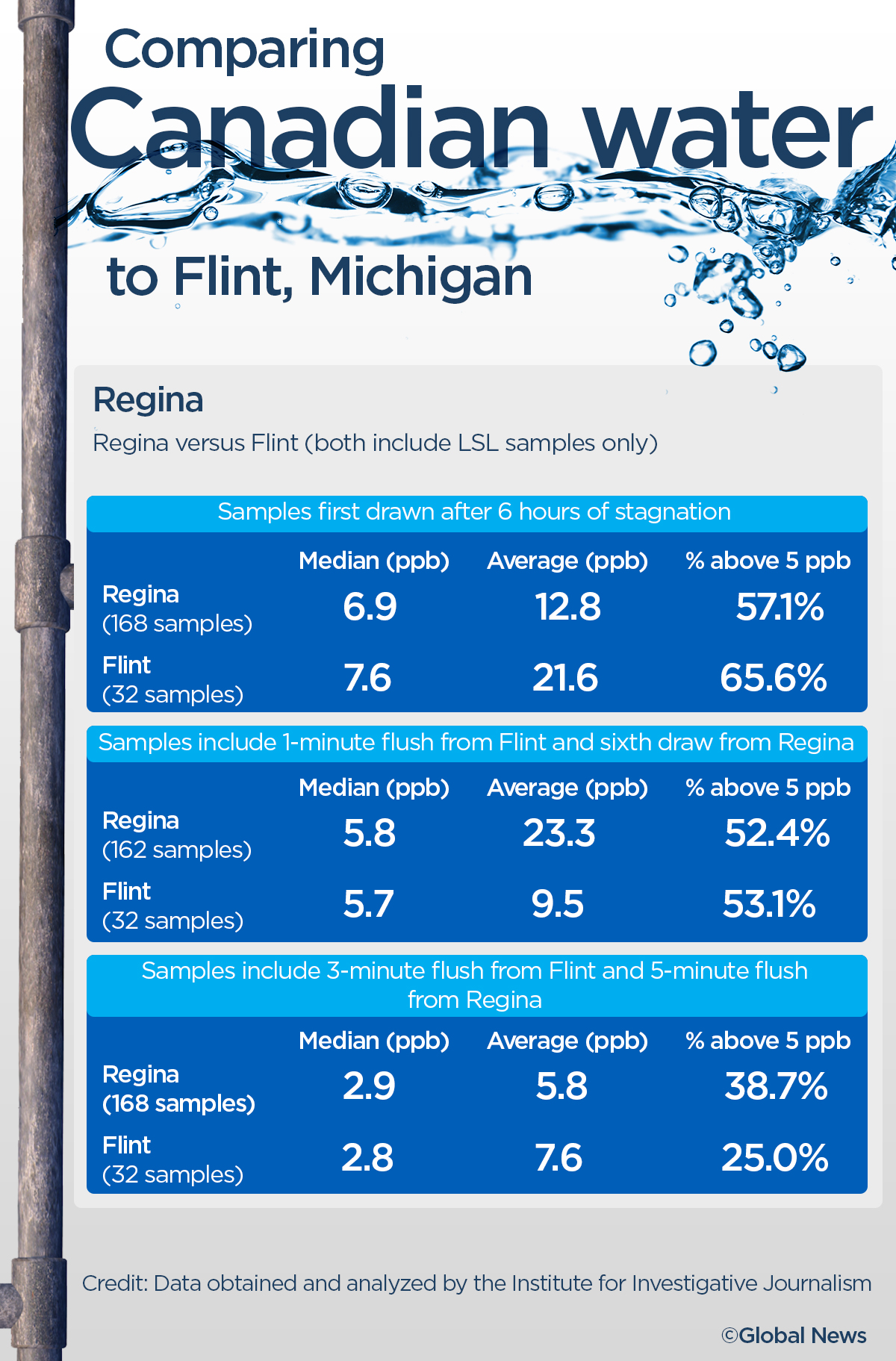

But test results for lead in Regina, Moose Jaw and Saskatoon homes suspected of having lead service lines are comparable to similar homes with lead service connections in Flint at the height of its water crisis in 2015.

In Regina’s homes with lead service lines, the fourth litre out of the tap in the morning — after just a minute of water use — averaged 26 ppb and in Saskatoon, 58 ppb. In Flint in August 2015, the same types of homes with lead service lines had lead levels averaging 10 ppb, also for the fourth litre out of the tap in the morning.

Documents released through freedom of information legislation by the City of Moose Jaw indicated that lead levels in 105 homes, suspected of having lead service lines, were 25 ppb in the first litre of water out of the tap in the morning.

In Flint, the same type of sample found lead levels of 22 ppb. Moose Jaw doesn’t take a sample for the fourth litre of water, which is generally the water that sits in the service line and could also contain lead that leaches from the pipes.

In Saskatoon, 94 per cent of tests in homes with lead service lines included results higher than five ppb after the taps were first turned on in the morning and releasing water that sat in the pipes for six hours. In Moose Jaw, 73 per cent of these types of samples, taken in the morning, were above the recommended five ppb limit. In Regina, this was true in 57 per cent of such homes — a level slightly below that of Flint, where 66 per cent of samples taken after six hours of stagnation wound up measuring more than five ppb of lead.

“I was asked several years ago by the press: ‘Do we have Flints here?’ And I said, ‘yes, we have Flints right across Canada because of the absence of regulation to push the numbers down,’” said Prévost.

All three cities said their own circumstances were different than Flint.

Regina said that 95 per cent of city-owned connections from its water mains to properties were lead-free and that it was working with residents to address the existing lead service lines. Saskatoon said that Flint’s crisis was prompted by a sudden change in its water supply. Moose Jaw said the comparison wasn’t fair since it was proactively testing water and informing households of the results.

Lanphear, the health science professor from Simon Fraser University in B.C., reviewed the data and judged it to be a fair comparison: “Flint, for good or bad, is now what we hold up as what’s galvanizing a lot of us to do better, to protect our kids from lead poisoning.”

The Saskatchewan Water Security Agency, which reports to Highways and Infrastructure Minister Greg Ottenbreit, said it was pursuing discussions with the water utility operators about how to improve practices.

The agency said that it could impose tougher conditions on the permits to operate for each municipality if it wanted to do so. But when presented with the numbers that showed the similarities with Flint, the agency said it was not yet time to impose any changes.

“So have we got to that point yet with communities? I don’t think so, but is that a conversation that’s happening today? Absolutely,” said Patrick Boyle, an agency spokesman, in an interview. “I would say we are taking action on a lot of fronts to have those conversations with municipalities, and with homeowners. So it’s a conversation that obviously, since Flint, Michigan, certainly has become top of mind. And that’s something that we’ve had for a number of years, is that increased testing and monitoring.”

Boyle added that Saskatchewan operates under a “robust” set of rules overseeing water quality as a result of a 2001 outbreak in North Battleford, when thousands got sick after the town’s drinking water supply was contaminated with cryptosporidium, a parasite.

The outbreak spurred a provincial inquiry that resulted in a set of recommendations, which he said the government implemented.

In Flint, the absence of corrosion control was the crux of the problem. Unlike the United States, there is no federal regulation in Canada on this practice, which consists of adding a non-toxic substance into the water that allows it to form a protective barrier on pipes that, as a result, reduces the amount of lead leaching into the water.

But both Moose Jaw and Regina say they are considering it.

“Our water treatment plant, Buffalo Pound, is actively considering and looking at that to help with lead levels,” said Josh Mickleborough, engineering director with the City of Moose Jaw.

“It’s not something that’s going to be corrected or removed from our distribution system overnight.”

Toronto, Ottawa and Quebec City all use corrosion control in their water systems and have lower measurements of lead in average samples than the three Saskatchewan cities, despite also having thousands of lead pipes underground.

But cities in Saskatchewan are also concerned about who will pay to replace lead pipes or to treat their water to make it less corrosive. Replacements require cooperation between cities and homeowners to ensure that the lead is removed on both sides of the property line.

In Saskatoon, homeowners have no choice but to replace their portion of lead pipes. The city removes lead pipes from the water main all the way to the house, assuming 60 per cent of the total cost and billing homeowners for the other 40 per cent. Experts have praised the city as a leader in North America for adopting this approach.

Under the program, Saskatoon allows homeowners to repay the city immediately or over three or five years; there are also other options for low-income property owners. All repayment plans are interest-free.

“Over the last number of years, the city has spent almost $20 million on replacing lead lines in Saskatoon and by 2026 we will be reaching the point where all of the lead lines in all private properties have been replaced,” said Angela Gardiner, Saskatoon’s general manager of utilities and environment.

And even though Regina’s testing protocols are quite rigorous, the pace of replacement is slow in comparison to Saskatoon.

“We are working on increasing our numbers,” said Pat Wilson, with Regina Water Waste and Environmental Services. “Because our individual lead service lines are scattered so much across the city rather than replacing whole sections, it is a much more scattered piece of work that we have to do.”

SaskWater, a Crown utility company that provides water services to dozens of communities representing 100,000 people in the province, warned the water security agency in 2017 that it would be difficult to comply with the new Health Canada guidelines for lead in drinking water, eventually adopted in 2019.

“It can be appreciated that this proposal will likely be a hardship for communities to comply with as the infrastructure that is responsible for the potential elevated lead concentrations in the drinking water is buried underground,” wrote Eric Light, vice president of operations and engineering at SaskWater, in a March 13, 2017 letter to the agency, released through freedom of information legislation.

“The cost to replace this buried infrastructure may be out of the reach of most communities in Saskatchewan. Even if a point-of-use solution in each household is considered, that will also be a significant cost.”

In a separate letter sent on March 14, 2017, the City of Prince Albert’s director of public works, Amjad Khan, told the agency that tougher limits on lead could “impose a significant financial burden” on water consumers.

When asked about these letters, Boyle, from the water security agency, noted that both the federal and provincial governments have been increasing infrastructure investments to help cities cope.

Lead most commonly makes its way into drinking water through lead service lines, but lead solder was also used in Canada up until 1986. The National Plumbing Code allowed lead materials in pipes until 1975 and restrictions on lead content in plumbing fixtures only tightened in 2014.

But with testing and replacement left optional for residents, the health and safety of them and their families are left to chance, and the onus placed on them to understand the health risks associated with elevated lead levels in drinking water, without access to the city’s data.

2,000 homes in Moose Jaw could have lead issues

Of Moose Jaw’s approximately 12,000 homes, about 2,000 of them (or 16.7 per cent) have lead service lines, according to Mayor Fraser Tolmie.

Currently, the city is responsible for the portion of pipe between the water main and the property line, while residents are responsible for the portion from the property line into the home.

Moose Jaw residents Craig Reichert and Roxanne Rath were first alerted that they might have lead service lines leading up to and on their property not long after they bought it about 10 years ago.

After the city tested their water, they said the results were mailed to them.

“They didn’t say anything. They just said here are your results and here’s what the normal level is,” recalled Rath. “(We were) quite surprised to find out, you know, not only that we had lead piping but how high of a content it was in our water.”

Journalism students from the University of Regina collected water samples at the couple’s home in March 2019. Lab results revealed lead levels of 14 ppb in the first litre out of the taps in the morning, 65 ppb after running the water for 45 seconds, and 7.1 ppb at the two-minute mark. The highest test result, which measured lead levels in water that sat in their service line overnight, was 13 times higher than Health Canada’s recommended limit.

“We’ve been lucky but how long is that going to last?” said Rath. “Neither of us are very young anymore so we really can’t take any chances with our health any more than we already have, I think.”

They say they still haven’t replaced their lines because of the cost and that the city won’t replace their portion until Reichert and Rath have replaced their side.

“If we have a break in (the pipe), then they’ll be forced. There’ll be an emergency repair and they said then it’ll cost us way more,” said Rath.

For now, both Moose Jaw and Regina offer residents free filters as part of their programs.

Regina estimates that it has about 3,600 lead service lines to replace on public property.

Saskatoon replaces between 300 and 400 lead services lines every year and estimates that it has just over 2,800 public lead service lines left to replace.

“Obviously the end solution here is replacement, you can talk about other treatment options, filtration and corrosion but at the end of the day the complete solution would be to have those lines removed,” said Patrick Boyle, spokesperson for the Saskatchewan Water Security Agency.

But with no data made public, residents say it comes down to transparency.

“The Flint, Michigan, thing certainly woke up a lot of people and made me think about it, but I still didn’t think Regina would let this happen to us,” said Wolfsen. “I feel like they were supposed to take care of us. They were supposed to assure that we had clean, safe drinking water, and they let us down.”

Investigative reporters, University of Regina:

Nathan Meyer, Kayleen Sawatzky, Rigel Smith, Dominique Head, Kaitlynn Nordal, Jacob Carr, Heather O’Watch, Dan Sherven, Joseph Bernacki, Ethan Williams

Faculty Supervisors:

Trevor Grant

Joe Couture

David Fraser

Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University:

Series Producer: Patti Sonntag

Research Co-ordinator: Michael Wrobel

Project Co-ordinator: Colleen Kimmett

Institutional Credits:

University of Regina, School of Journalism

Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

See the full list of Tainted Water series credits here: concordia.ca/watercredits.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.