TORONTO – How many times have you texted “I gotta go to work” or “my battery is about to die” to avoid a conversation?

What about telling a white lie on your friend’s Facebook wall after they post photos of their new puppy? “So cute,” you write, despite the fact their new pet looks like a dirty, wet rat.

According to experts, if you’re like most people, you are a liar. And you lie once or twice a day.

Forensic cognitive psychologist Dr. Coral Dando says subtle lies like the above are part of how we manage our everyday social interactions to the best effect; to avoid conflict with friends and family. But research shows that even serious, outright lies—when information given is completely at odds with the truth—are also a daily occurrence.

“Some have found that in the 10 minutes that it takes to get acquainted with someone new, people lie an average of 2.18 times – lying about their academic achievements, finances, and experience,” Dando wrote in an email to Global News, citing 2006 research by Tyler.

“Diary studies have consistently revealed that people lie on a daily basis – undergraduate students reported lying twice a day, and the general public once a day, most of which were outright lies (68 per cent),” wrote Dando, citing 2006 research by Engles, Finkenauer, and van Kooten, and a 2001 paper by Bleske and Shakelford.

But why is that? Has the Internet made lying easier for us?

Cornell University cognitive scientist Jeff Hancock’s research says yes…and no.

Take your resume, for example.

In a study comparing deception in LinkedIn profiles to paper resumes, Hancock and his team predicted there would be less lying online for two reasons: LinkedIn profiles are public, so a number of people can easily fact-check them, and LinkedIn is a network, linking people who know you well and who you wouldn’t want to think you are a liar.

But at first glance, they didn’t see this effect overall. Why not?

However, people lied less on LinkedIn about the things that matter most, such as job responsibilities, skills and abilities, which means these online profiles still contain truth, and are still a great tool for employers.

Tricky texts

Get breaking National news

When it comes to text messaging, Hancock’s studies suggest about 8 to 10 per cent of texts are deceptive. His research highlights one function of text messaging called micro-coordination: the way we plan to meet up with friends and coordinate social interactions.

Cell phones, which are designed primarily to make it easier for people to connect, have made it so that people are always available: once you have someone’s number, you can technically always get a hold of them.

Hancock said this relates to one type of “old” lie that has been modified with our current technology: the butler lie.

The butler, the sock puppet and the Chinese water army

“Back in the day, you’d have a butler that would say, ‘oh no, Master Hancock is otherwise engaged.’ Now I do that myself, using the ambiguity that comes from you not being able to see me or hear me,” he said.

A simple text saying “sorry I’m busy” or “I’m in a tunnel” uses the ambiguity to create a buffer that has gone away – so texting becomes a social solution to using an actual butler.

Another type of lie is the sock puppet lie – when a person pretends to be someone else in order to self-promote. Hancock cites poet Walt Whitman as someone who was caught writing positive book reviews for himself under another name, which occurred pre-Internet.

“The sock puppet is old, but new in the way that it’s just so much easier to do,” said Hancock. “There’s something about the ease of being able to write online reviews that makes it more of a threat.”

MORE: Visit reviewskeptic.com to test Hancock’s current research tool that aims to detect fake online reviews.

This takes us to the third type of lie, which Hancock argues is new and owes its strength and scale to the Internet: the Chinese water army.

“The Chinese water army refers to the government and other organizations in China, paying people small amounts of money to write social media and propaganda for them,” he said.

These organizations can pay around 30,000 people as little as 50 cents to write propaganda in various social media, such as Weibo. Hancock said this makes it look like there’s a grassroots movement that’s “against whatever the government is against.”

Hancock said in Canada and the U.S. it’s called “astroturfing” – a play on the term “grassroots.” He said this is a new type of lie not seen before in humanity – the ability to get many people together to facilitate a deception.

“We see around elections, especially organizations, corporations, and politicians will pay people to write things online, to sign petitions, to show up, to rally…and it’s all done via social media.”

Written records and the truth bias

These three types of lies have something in common that didn’t exist to the same extent prior to widespread access to cell phones and the Internet: there’s a record of all of them. And that may be linked to something called the truth bias.

Hancock calls it the “single most reliable finding with deception,” and it means we are more likely to believe something to be true than not.

Dando believes the main reason for this default setting in social interactions is because it’s easier.

“People naturally assume one is telling the truth until they discover otherwise because the former approach is less cognitively demanding than the latter,” she wrote.

And according to Hancock, this bias is even stronger when it comes to the written record.

Because we’re not used to leaving a record, it’s lately been the undoing of politicians or businessmen who leave digital records they didn’t mean to leave.

But these records also allow scientists like Hancock to study language in ways they couldn’t before, since in the past, they simply disappeared.

“All we could analyze, even 20 to 30 years ago, were things like newspapers or books or encyclopedias, because the average person didn’t write very much,” he said. “Now people will write more in the morning than was written in almost all of pre-history.”

Scientists are hoping these records will allow them to improve upon the accuracy rate of detecting lies, which Hancock says is currently at only 54 per cent.

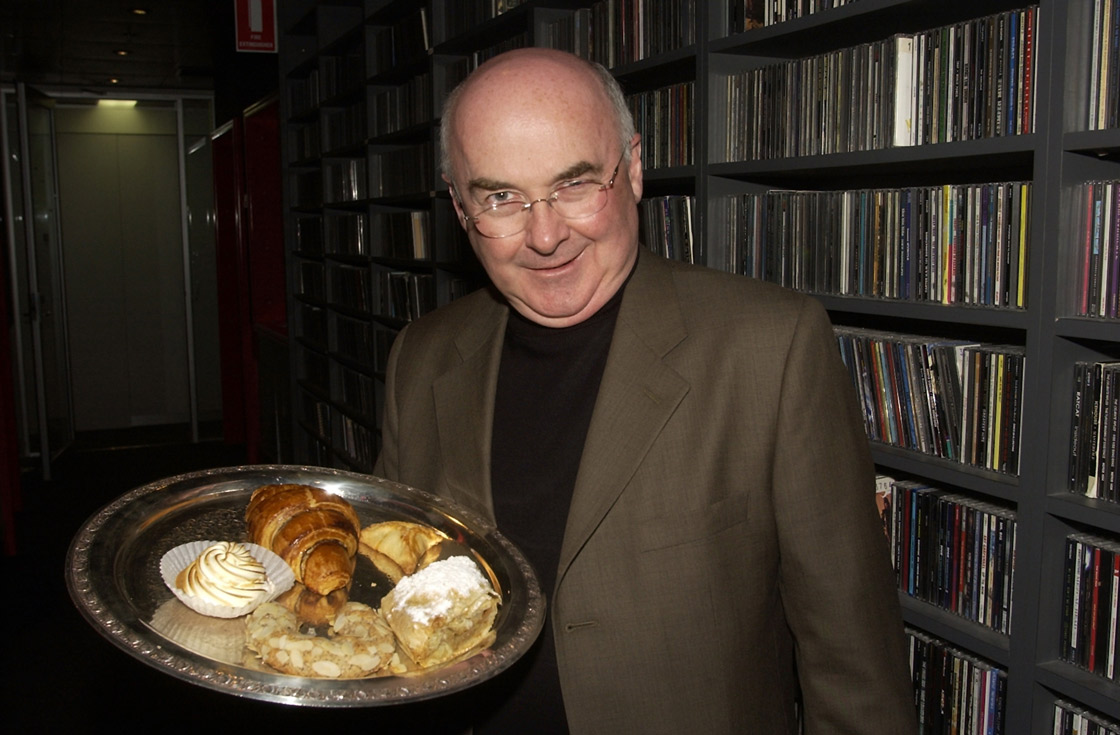

Jeffrey Hancock is an associate professor of cognitive science and communications at Cornell University, conducting research that focuses on verbal irony, deception, as well as cognitive and social psychological factors affected by online communication.

Dr. Coral Dando is a Reader in Applied Cognition at the University of Wolverhampton. a forensic psychologist, chartered scientist and former police officer with the Metropolitan Police in London, UK. Dando’s primary research interests are centred on cognition in interview settings, and how contemporary psychological theory and empirical research can inform front line interview practice.

Comments