Ragne Reid faced a lot of scrutiny when she became pregnant with her son, Jax, while her nine-month-old daughter, Mira, was undergoing cancer treatment.

“My family doctor suggested that I have an abortion, but we were trying so hard to save the life of our daughter, there was no way I could justify ending the life of another baby,” she told Global News.

“I was seeing a chiropractor at the time who shook his head and told me that I needed to be more careful. That was the last time I saw him.”

READ MORE: Caring for the caregiver — Raising a child with a disability or chronic disease

Reid, who lives in North Delta, B.C., also faced criticism from friends.

However, Reid and her partner were told that Mira’s cancer didn’t have a genetic component so they just tried to “shrug it off.”

Helping parents understand the “cause” of the first child’s illness or disability should be a top priority for primary caregivers, according to Dr. Peter Azzopardi, chief of pediatrics at the Scarborough Health Network.

“Most worrisome to me is, often, a parent tries to assign blame in terms of what happened to the first child,” he said.

“It’s important to get to the bottom of that issue so the parent doesn’t feel like the cause of that issue.”

In his view, it’s only with a full understanding of the first child’s condition — and the risk that it could be passed on — that parents can make an informed decision about having another child. This often requires an extensive amount of genetic testing, he said.

Genetic testing helps parents understand risk

“The most important thing is what is the nature of the child in the family that already has the disability?” Azzopardi said. “What is the problem and what is the risk that it could be passed on?”

If the problem is defined as potentially having a genetic component, the parents will be tested in order to determine the risk of it affecting another baby. Some illness and disability will be genetic, but others will have “nothing to do” with a family member having risk — like issues that arise at birth.

Regardless of the results, genetic testing helps parents to do away with the common feelings of guilt or shame that can occur after welcoming a child with a disability.

READ MORE: ‘It has made me a better person’ — What it’s like to raise a child with autism

Get weekly health news

For Nicole Boucher, a mom of two based in Toronto, genetic testing helped her feel more in control, even if only slightly.

She and her partner have always wanted a big family, but her first pregnancy didn’t go as planned. During an ultrasound, doctors found a cyst in the back of her son’s brain that caused it to form differently.

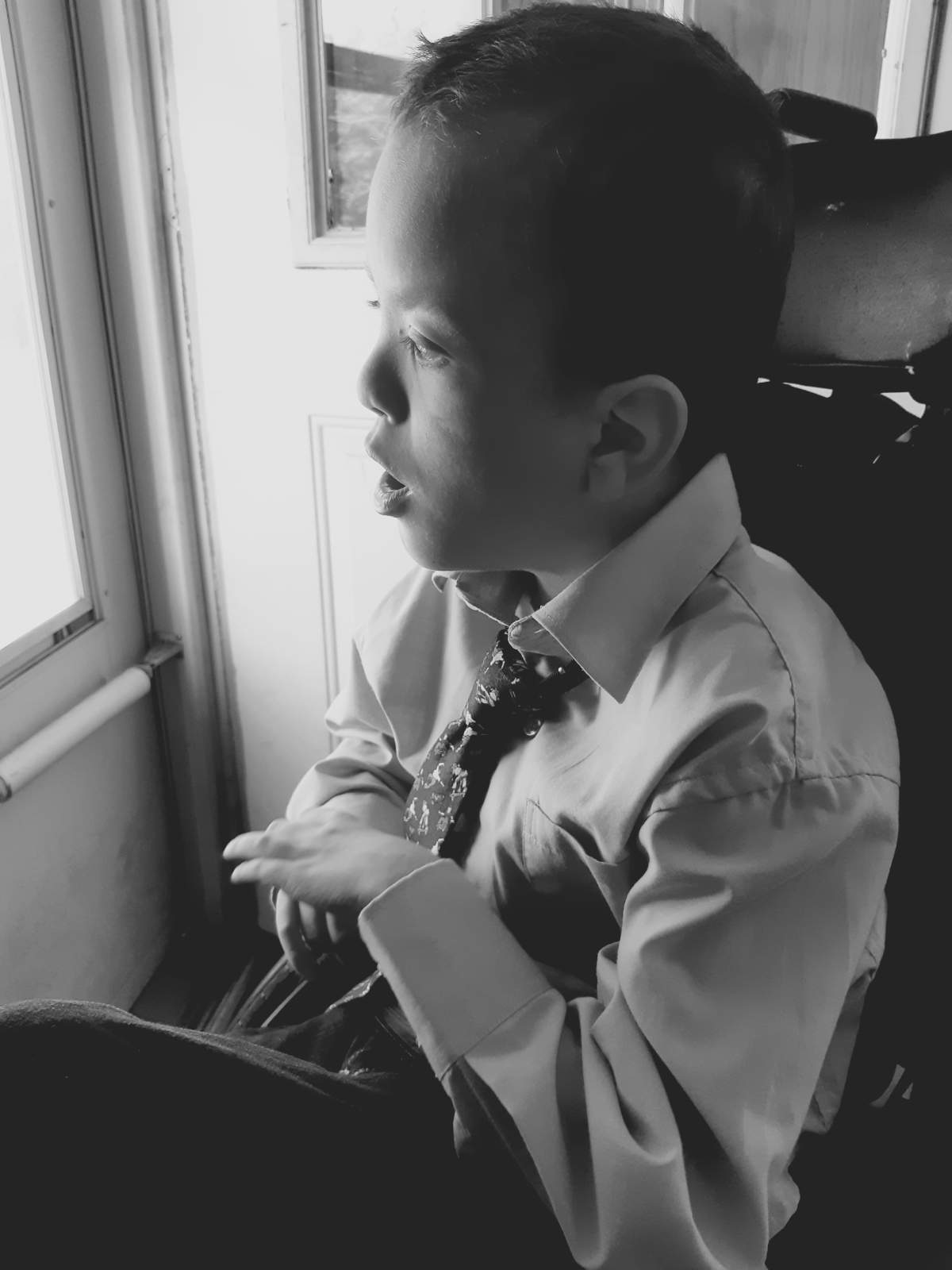

After her son Jacob was born, doctors performed genetic testing to determine the details of his illness.

“He has a single gene mutation that they’ve never seen before. They don’t know what it means and they can’t really give us a prognosis,” said Boucher.

However, doctors were able to determine that he has epilepsy, a development delay and visual impairment.

The genetic testing also showed that Jacob’s condition was de novo, which meant neither of the parents were carriers. “That was one of our biggest fears.”

For Jacob’s first year of life, his parents were just focused on “keeping him alive.” But with the genetic testing on their side, they decided to “let whatever happen, happen,” said Boucher. “And along came Caden.”

Having another child is ‘such a personal decision’

In Azzopardi’s experience, it’s common for parents in Reid and Boucher’s position to face stigma about having another child.

Ultimately, Azzopardi believes parents know what is best for their family, and Calgary-native Rachel Martens agrees. She works at CanChild, a non-profit research and educational centre that focuses on improving the lives of children with developmental conditions.

READ MORE: Like mother, like daughter — Living with the same disease as your mom

“There are many things to consider from a couple different lenses,” said Martens. “Do you have a sufficient support system in your life to help your family? Is your significant other prepared to take on added responsibilities?”

Choosing to have another child is a complex decision in and of itself — disability or illness just adds to that.

“The uniqueness of who you are as a parent and a person plays a role in this decision,” she said. “It’s important to remember who you are in this and to never apologize to others when it comes to whatever future you decide for your family.”

Martens is also mom to a 13-year-old boy who has Mosaic trisomy 22, cerebral palsy and autism. She and her partner decided not to have any further children, and it works for them.

“For us, the decision came with working towards who we felt our identity was as a family unit. We make a heck of a trio.”

Finding non-judgmental support from the health-care system

While Mira was in treatment, Reid had enough on her plate without taking into account the judgmental comments and unsolicited “advice” from those around her.

Mira finished treatment in December 2010, and Jax arrived — healthy and happy — in February 2011. Reid was overwhelmed.

WATCH: How a community can deal with children and youth to help break the cycle of poverty

_848x480_1523929155690.jpg?w=1040&quality=70&strip=all)

Reid said she tried to find a psychologist, but due to time and location constraints, it wasn’t possible. On top of that, she was struggling to learn about how to navigate the hospital system.

“It’s so complicated and difficult to navigate,” said Reid.

Supporting parents like Reid is Joanne Doucette‘s job. Doucette is a social worker at the Child, Adolescent and Family Centre of Ottawa, and she’s seen first-hand the difference support from a person like her can make.

READ MORE: Becoming a father can negatively impact men’s mental health: survey

“My role is to look at each family’s situation. Each is so unique and so different,” she said. “When a first child has a really complex medical condition, often there are a lot of questions about whether another child will have the condition as well.”

In helping parents decide whether they want to expand their family, Doucette focuses a lot on ensuring they have a robust support system — whether it’s family, friends or a health-care professional.

“It takes a village to raise a child — and I think that goes for every single family — but when a child has a medical illness or disability, the need for that village is just that much bigger.”

One of the things social workers and therapists should do is provide emotional support, helping parents work through those feelings of guilt and shame so they can “be in a place where they’re able to make those decisions more clearly,” she said. “I support parents whichever way they go in terms of making those decisions.”

Ultimately, the taboo around having another child after your first falls ill or is diagnosed with a disability remains taboo. Breaking down that stigma is, in part, the responsibility of primary caregivers.

“Parents are the best experts on what they need for their kids and what they need for their family,” said Doucette.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.