In 1980 the average price of a house in Canada was five times the average income. Today, it’s around 10 times.

Renters aren’t faring much better. According to a recent report, the minimum wage it takes to afford a two-bedroom unit has risen from just over $17 per hour in the 1990s to $20 an hour after adjusting for inflation — and that’s excluding the private, and much pricier, condominium rental market.

WATCH: By the numbers — renting compared to owning

Housing affordability was part of the Liberal Party’s 2015 campaign pitch to the middle class.

“Today, one in four Canadian households is paying more than it can afford for housing, and one in eight cannot find affordable housing that is safe, suitable, and well maintained,” reads the Liberals’ platform from the last federal election.

Justin Trudeau promised a series of measures to help turn that ship around, including more public funding to build affordable housing units, refurbish existing ones and a “review” of skyrocketing home prices in markets like Toronto and Vancouver.

*Note: Home prices and incomes in the chart below are in 2017 dollars.

After nearly four years of Liberal government, here’s a look at some of the government’s major initiatives and how they’ve fared:

For homebuyers:

The mortgage stress test

What it is:

The mortgage stress test is arguably the best-known housing measure of the Trudeau government. The news rules, which were implemented in two phases between 2016 and 2018, established stricter standards for federally-regulated lenders to vet Canadians applying for a mortgage.

The regulations are an attempt to rein in household debt loads by vetting borrowers against interest rates higher than the mortgage rate offered by their bank. This effectively imposes a lower cap on the maximum mortgage amount a given borrower can obtain, which has forced some prospective buyers to settle for less expensive homes or to postpone purchases in order to save for a bigger down payment.

The first iteration of the stress test came into effect in October 2016 and applied only to Canadians seeking a mortgage with a down payment smaller than 20 per cent of the home value, which requires government-backed housing insurance. The test checks whether a borrower would be able to keep up with mortgage payments based on the greater of their contractual rate or a benchmark interest rate set by the Bank of Canada, which is usually far higher than the rates offered by many lenders.

In January 2018, the government rolled out similar rules for buyers with down payment of 20 per cent or more, covering so-called uninsured mortgages. The bar for these borrowers is either the Bank of Canada’s benchmark rate or their contractual rate plus two percentage points, whichever is greater.

READ MORE: With fixed rates below variable ones, mortgage market is in the Upside Down

Did the stress test calm the housing market?

Buying a house still looks like a pipe dream for Canadians with middling incomes in Vancouver and Toronto and has become more of a stretch in places like Montreal. But since around 2017, the national home price growth has slowed down considerably, with property values falling in many of B.C.’s priciest markets.

In other words, things aren’t great, but they’re definitely less bad than if homes had kept appreciating at the rate did were in 2016.

Did the mortgage stress test do that?

The answer is tricky because the implementation of the federal rules overlapped with provincial and local measures that also aimed at taming runaway prices in B.C. and Ontario. Beijing’s imposition of tougher checks on money moving abroad likely also played a role, by making it harder for wealthy Chinese investors to buy property in places like Vancouver.

Still, the tighter federal mortgage regulations were “100-per cent a factor” in pulling the brakes on a real estate market, according to Toronto mortgage broker Robert McLister.

Get weekly money news

“When you have an engine that runs too hot, it blows up,” said McLister, who is also the founder of mortgage rates comparisons site RateSpy.com.

The mortgage stress test “was appropriate, it did its job. It wasn’t too much tightening,” McLister said.

READ MORE: Most boomers likely won’t downsize for another 20 years — too late for millennials

But Thomas Davidoff, professor and housing expert at UBC’s Sauder School of Business, won’t go as far as to say the stress test was the main factor that turned things around.

Both in Vancouver and Toronto, it was the most expensive section of the real estate markets — detached homes worth upwards of $1 million — that saw the biggest impact on prices, suggesting that provincial and local measures targeting real estate investors may played a bigger role, Davidoff said.

WATCH: Is too much of your wealth tied up in real estate?

The First-Time Home Buyer’s Incentive

What it is: After tightening the screws on the mortgage market, the Trudeau government introduced the First-Time Home Buyer Incentive in the 2019 budget, billing it as an effort to help cash-strapped buyers afford their first home.

The program, which launches on Sept. 2, allows homebuyers to take out a smaller mortgages with lower monthly payments thanks to a government-funded down payment top-up of up to 10 per cent of the price of a new home. The incentive comes in the form of a second mortgage with no interest and no regular payments. Homeowners can repay the loan at any time with no pre-payment penalty, but the loan becomes due after 25 years or when you sell the home.

The amount to pay back is based on the value of the home at repayment. For example, say you buy a new home for $200,000 with a 10 per cent incentive from the government of 20,000 dollars. After a few years, you sell the house for 220,000 dollars. You now have to repay the incentive as 10 per cent of the current home value, or $22,000. On the other hand, if your home price went down, and you sold the house for, say, $180,000, the government would take a loss. You’d have to repay just 18,000 dollars.

Still, Global News calculations suggest that, over a 25-year period, you may have to pay back to the government more than you’d save in mortgage payments through the program, even assuming modest home price appreciation.

In order to qualify for the incentive, you must have an annual income of no more than $120,000, while the maximum mortgage amount is capped at four times your income plus the incentive amount. That means the most expensive home you can hope to buy under the plan would be worth somewhere around $500,000, depending on the size of your down payment.

READ MORE: Is the First-Time Home Buyer Incentive a good deal for homebuyers?

Will this help homebuyers?

James Laird, a Toronto mortgage broker at CanWise Financial and co-founder of Ratehub Inc., doesn’t see any upsides for buyers.

“I can’t really think of a single buyer for whom this offer would be attractive,” Laird told Global News when details of the incentive were revealed in June.

Laird also pointed out the program imposes a mortgage cap that is even lower than that built into the mortgage stress test. But homebuyers who don’t want to borrow the maximum the would qualify for under the current federal rules can simply opt for a smaller property, without taking out a complicated loan from the government, Laird said.

But Heather Tremain, CEO of the Toronto housing non-profit Options for Homes, has a different take.

“I think it’s a good program,” she told Global News. “It is designed to have an impact but not to undermine the work that was done bringing in the stress test.”

The incentive, she added, is meant for buyers who wouldn’t otherwise be able to purchase a home.

“If someone can get into ownership at the same cost as their rental then there’s the advantage that they’re building equity over time,” she said.

At the same time, the program’s implicit low price cap means it won’t stimulate demand in already pricey real estate markets like Toronto and Vancouver, she said. Instead, the incentive will likely appeal to prospective homebuyers in smaller urban centres, she added.

WATCH: The First-Time Home Buyer Incentive explained

For renters:

Affordable housing

When it comes to renters, the Liberal government has been focusing on adding affordable housing. Public spending on social housing fell off a cliff in the early 1990s, with the number of new rental units with committed financing dropping from around 20,000 a year through the 1980s to less than 5,000 a year by the mid-1990s, according to data published in a recent report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA).

READ MORE: $22/hr is average wage needed to afford a two-bedroom apartment in Canada, says report

Since 2017, the Liberals have announced a $55-billion, 10-year National Housing Strategy (NHS) to be spearheaded by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), which administers most federal programs related to affordable housing. The strategy aims to remove more than half a million families from housing need, create up to 125,000 new housing units, and refurbish more than 300,000 public housing units, while cutting chronic homelessness in half.

READ MORE: There’s a lifestyle penalty for renting in Canada — it doesn’t have to be so

When it comes to building rental housing, not all of the federal programs that have coalesced into the NHS have been equally successful so far, but the money “is making it out the door,” said David Macdonald, who authored the CCPA report.

The number of new affordable units that received public financial commitments in 2018 was 16,600 compared to just 5,900 in 2015, Macdonald said.

Still, while that’s a significant improvement, it remains lower than the average number of new units the government was financing annually in the 1980s.

“We are not back to where we were,” Macdonald said, “and we have 10 million more people today.”

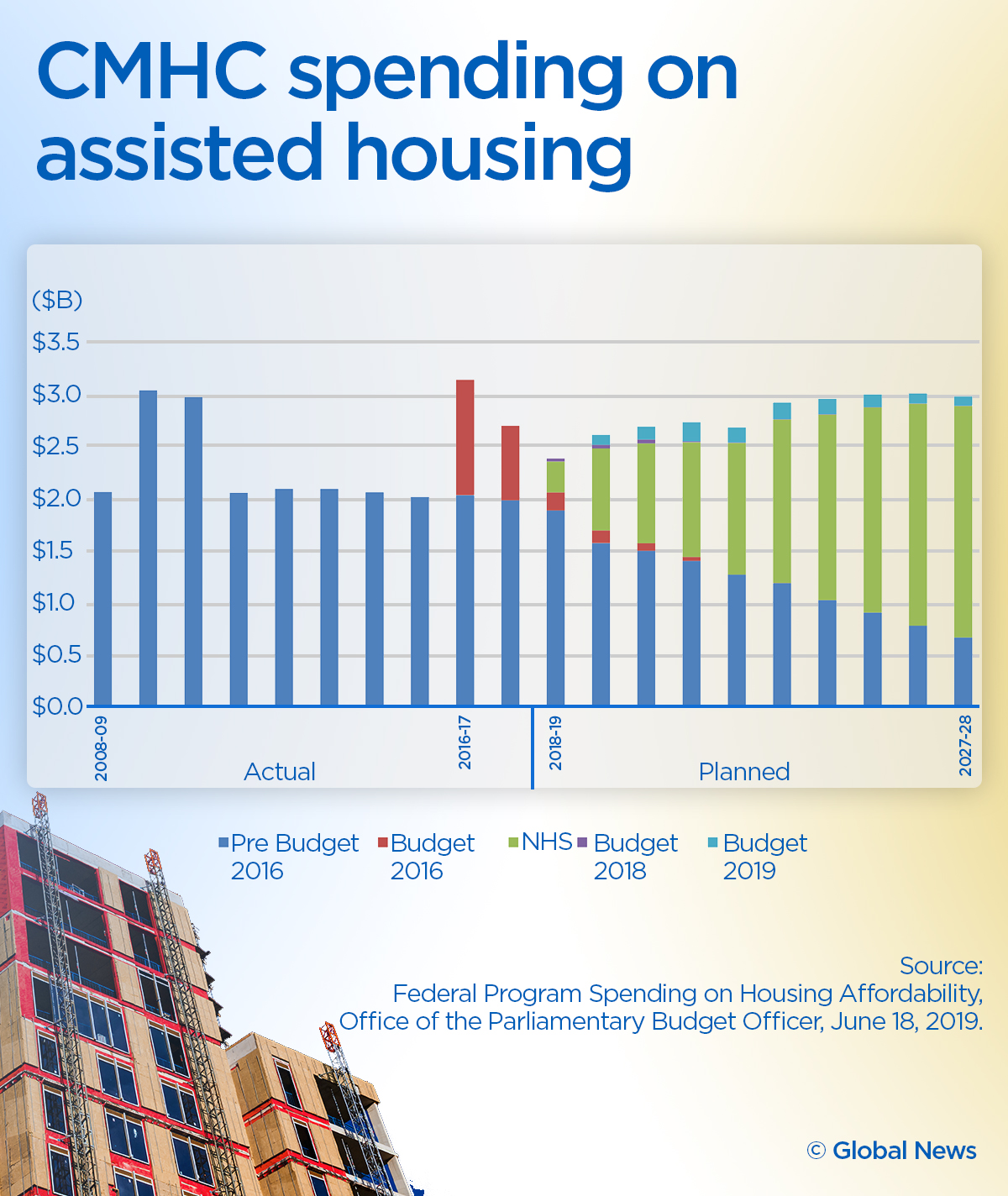

There is also the question of whether the NHS is as ambitious as its $55-billion price tag would suggest. A recent study by the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) found that the strategy amounts to just $16.1 billion in new federal planned spending. The rest of the money represents pre-existing spending commitment, government loans and provincial and territorial cost-matching.

READ MORE: Parents aren’t just helping their kids buy homes — they’re helping pay rent

The NHS boosts the CMHC’s annual spending on assisted housing by just 15 per cent compared to the average of the past 10 years, according to the PBO report.

“It is not clear that the National Housing Strategy will reduce the prevalence of housing need relative to 2017 levels,” the PBO said.

Still, without the NHS, CMHC funding to assisted housing would have dropped by more than 70 per cent by 2027-28 due to the expiry of previous time-limited investments.

Macdonald said Ottawa’s renewed commitment to those sunsetting government programs was not a matter of course.

“The experience of the 1990s is that no, they would not automatically have been renewed,” he said. “It is certainly possible for the federal government to completely get out of the affordable housing business.”

WATCH: How rent-to-own works

The Canada Housing Benefit

Building more affordable rental housing isn’t the only way to help Canadians who have a landlord instead of a mortgage. The Liberals’ proposed Canada Housing Benefit (CHB) would take a different route, by giving Canadians money to help pay rent.

The CHB, which was announced as part of the NHS, would provide cash transfers averaging $2,500 a year to some 300,000 families in need starting in 2020.

While the size of the benefit is large enough to make a significant difference for recipients, the number of renters who will receive it is small, Macdonald said.

In 2020, half of the 4.8 million families who will rent their homes that will be either unaffordable, unsuitable or inadequate according to CMHC standards, according to Macdonald’s report.

While the CHB represents “the other piece” of the Liberals’ housing strategy, “it’s not nearly as large in terms of aggregate impact,” he said.

Besides, the CHB, like much of the new funding for the Liberals housing strategy, is booked for “beyond this government’s mandate, and in many cases, beyond the next government’s mandate,” Macdonald said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.