Just a block away from Toronto‘s upscale Yorkville neighbourhood is a glass office building lined with trees. The trees — ginkgo biloba — provide shade on hot summer days, clean the air and are pretty to look at.

But while city planners love them for their cleanliness, for anyone suffering from seasonal allergies or asthma, these trees could be making symptoms worse.

That’s because they’re male. And unlike their female counterparts, distinctly male trees produce pollen.

“I am truly concerned,” said Dr. Christopher Carlsten, a professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia whose work focuses on the “compounded” effects people with asthma experience when exposed to multiple pollutants, such as pollen and vehicle exhaust.

“In the most susceptible individuals, their airflow can drop almost 50 per cent from its baseline by virtue of that combination,” he said.

According to Asthma Canada, roughly seven million Canadians have seasonal allergies, while approximately four million people suffer from asthma. Symptoms include itchy eyes, runny noses, coughing and shortness of breath. In some cases, asthma can be fatal.

And while extended growing seasons and rising carbon dioxide levels have been linked to increased pollen production, Canada’s urban forests also have a disproportionately high number of pollen-producing trees and shrubs. According to a 2012 survey commissioned by the makers of the anti-allergy drug Reactine, urban forests in 11 major Canadian cities ranged between 74 and 98 per cent male when looking at single-sex species.

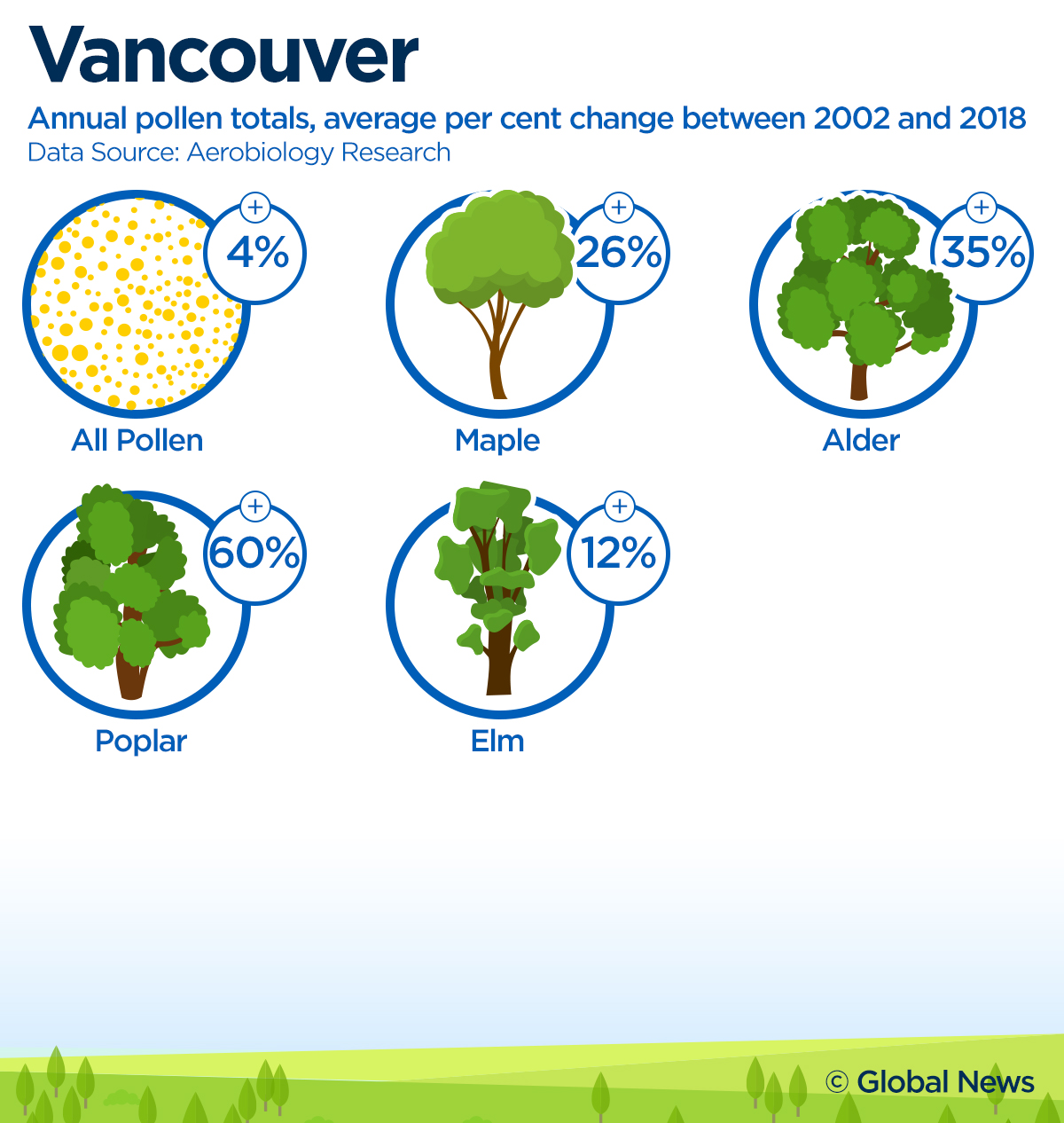

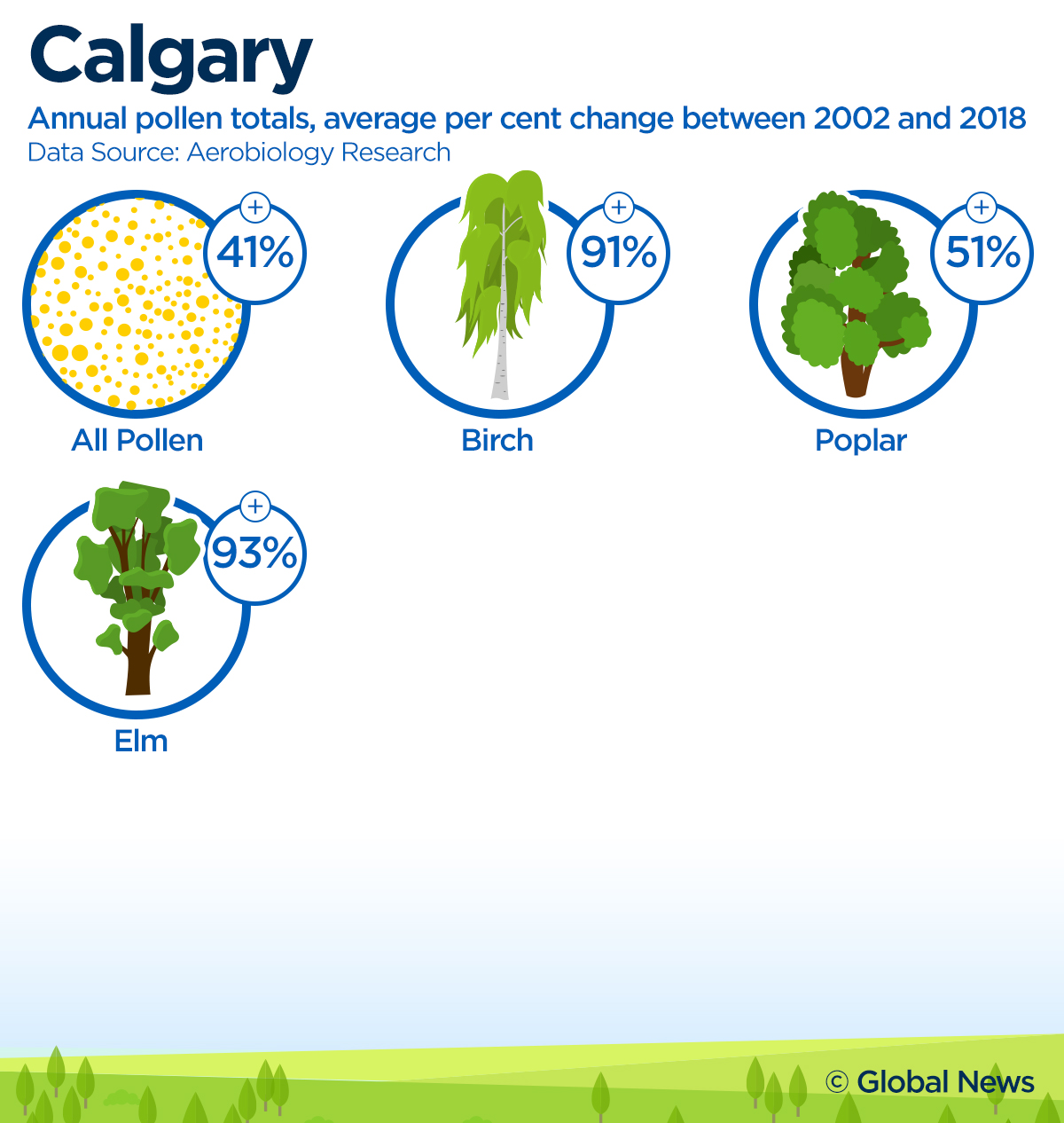

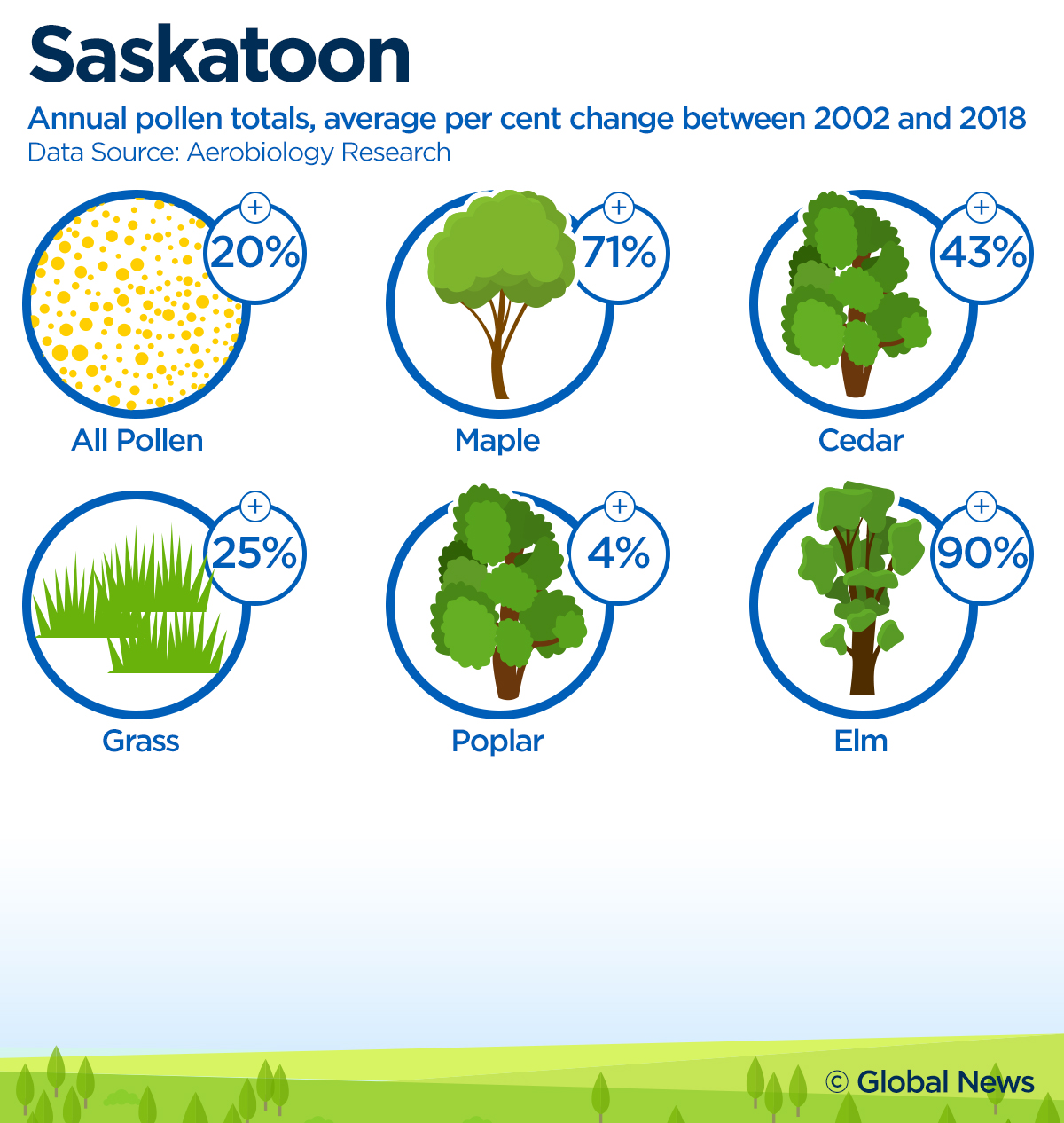

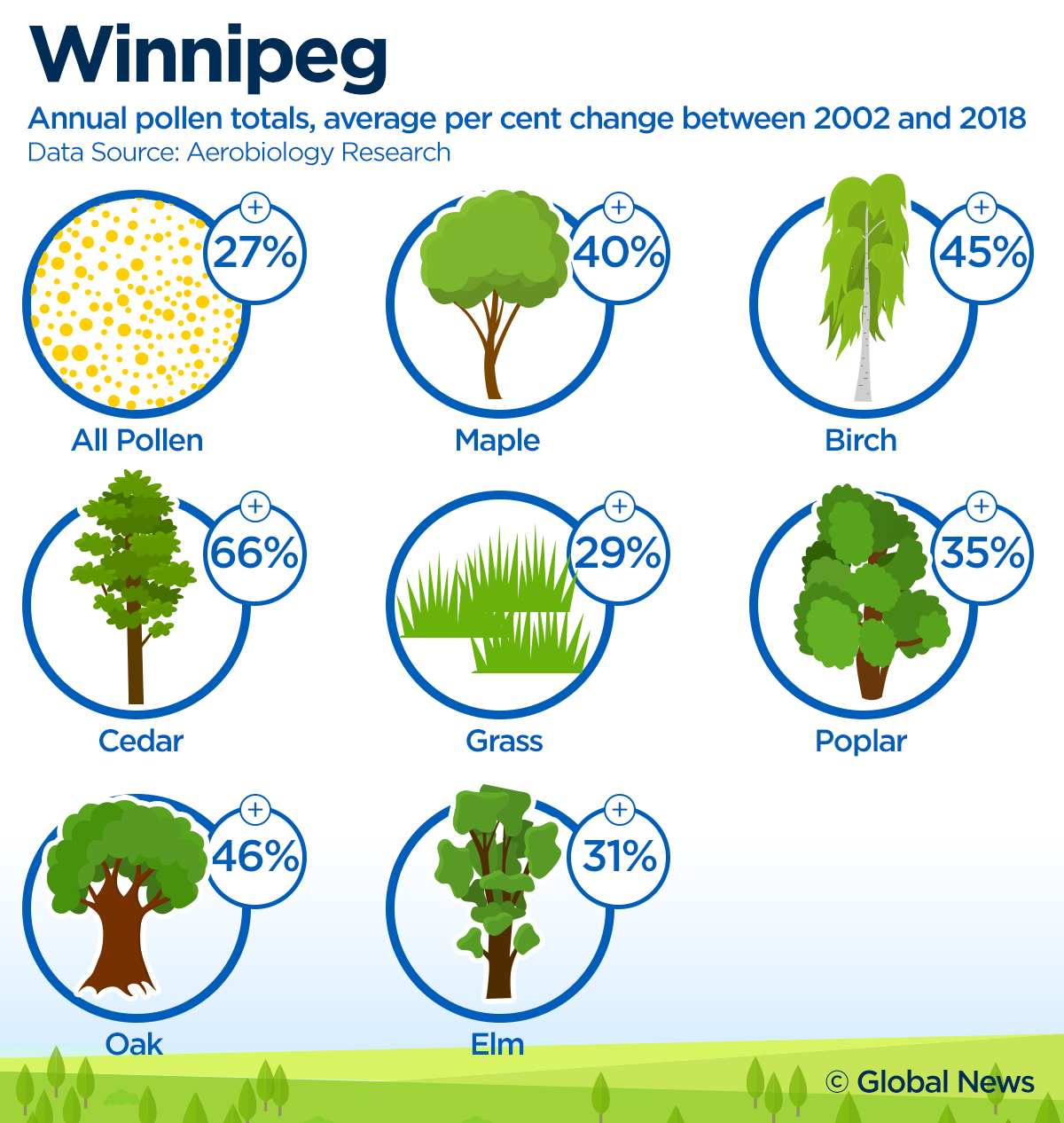

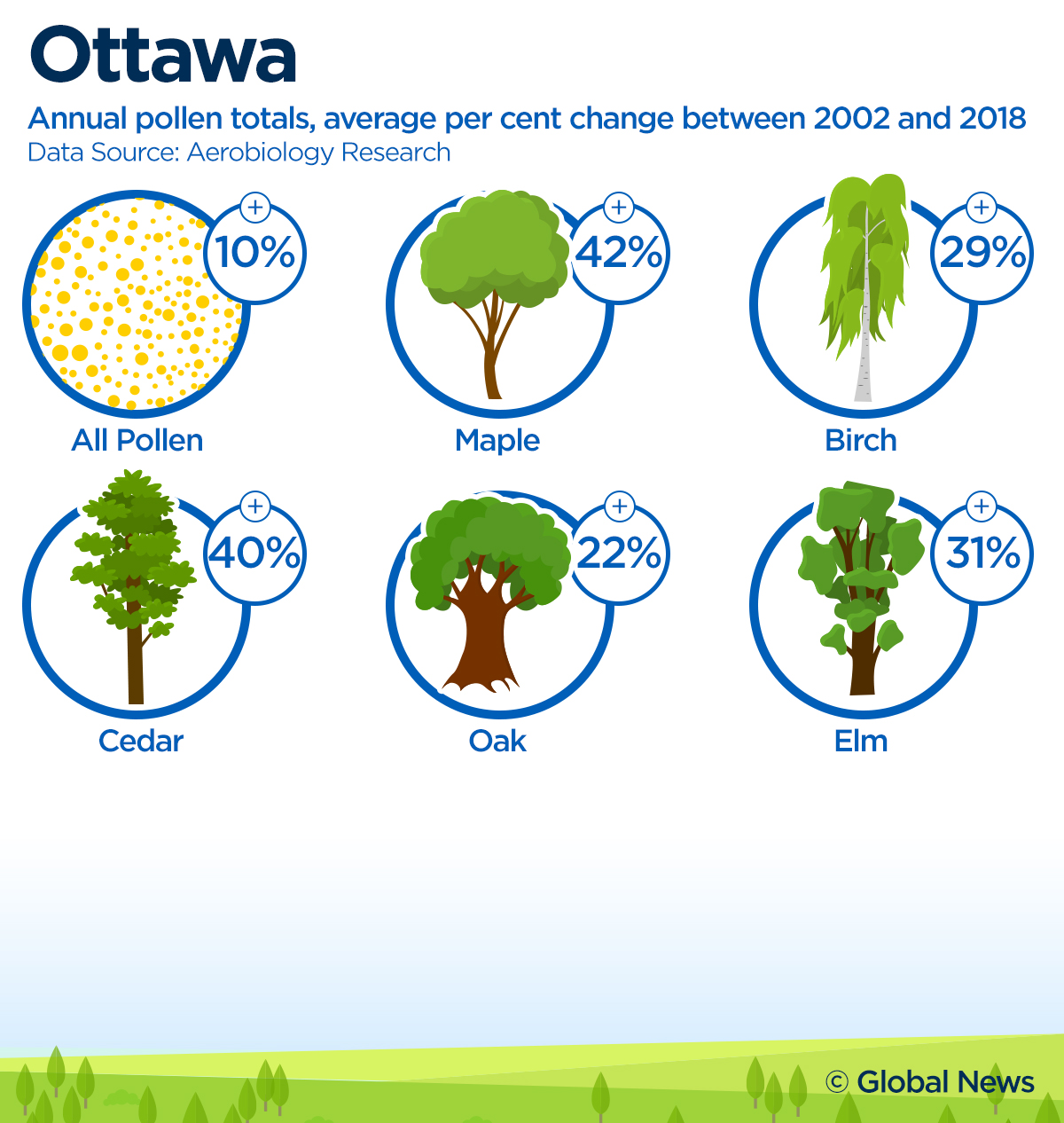

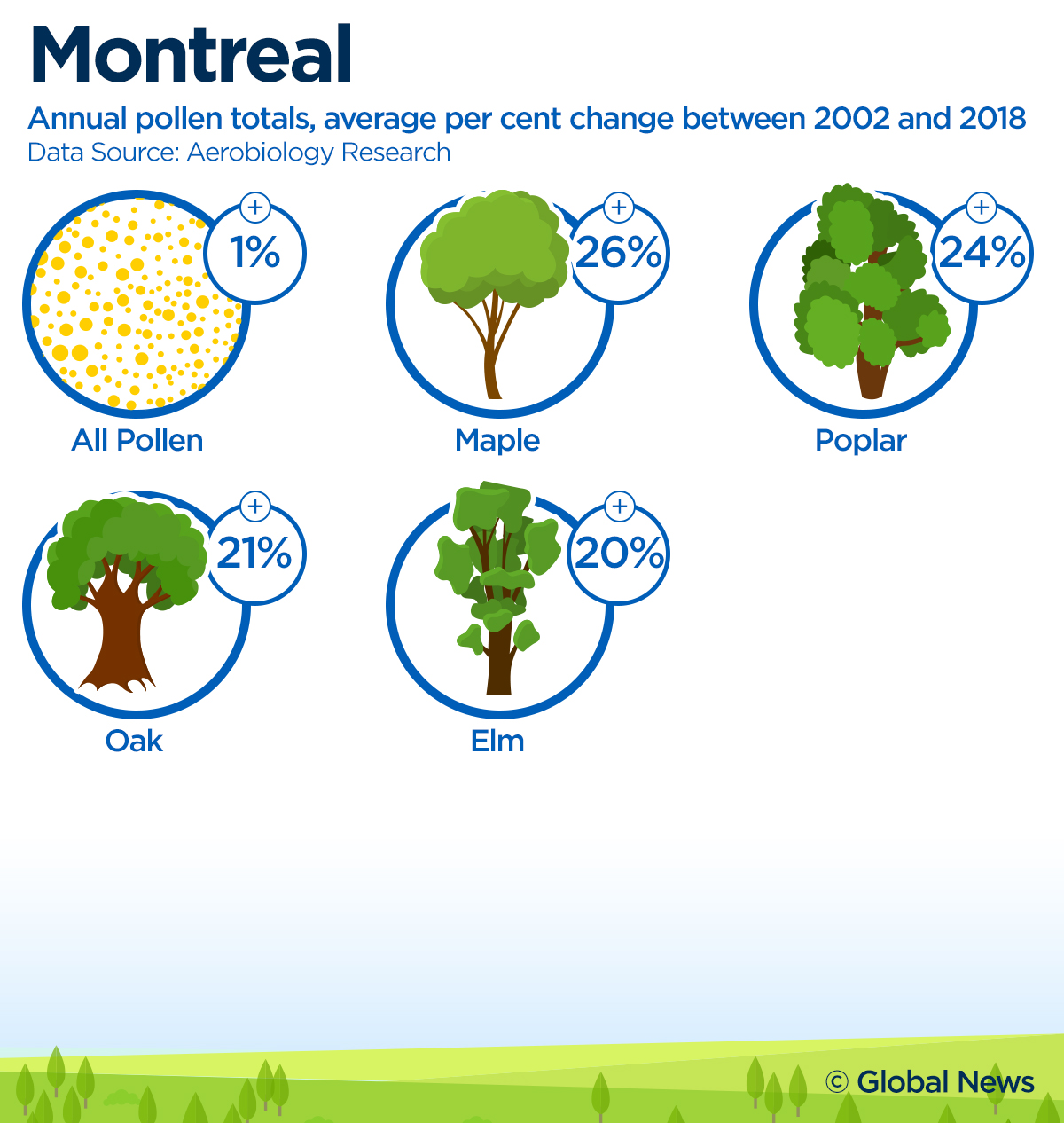

Data from Ottawa-based Aerobiology also shows that cities from Victoria to Montreal have seen significant increases in pollen levels over the past fifteen years — including big jumps in specific tree and grass pollens.

This has led horticulturalists, medical doctors, foresters and research scientists to say it’s time local governments take a closer look at the types of trees they use, paying particular attention to how increased pollen levels contribute to people’s overall health.

“This is such an important issue that affects people citywide,” Carlsten said. “It’s incumbent on the cities to consider the full range of potential benefits, harm and adverse effects — or unwanted effects — of male versus female.”

Why use male vs. female trees?

There are different kinds of trees — some male, some female and some both.

Dioecious trees — those that are distinctly male or female — have flowers with single-sex organs. Examples include certain varieties of cedars, poplars, willows and ginkgo.

The iconic Manitoba Maple — and many maple varieties — are also dioecious. City planners across North America use these trees because they’re hearty and can withstand harsh winters.

WATCH: Botanical sexism triggers allergies

Monecious trees, meanwhile, have both male and female flowers — typically, one branch is all male and another branch is all female.

There are also cultivars (cultivated varieties) that can be engineered to be male, female or both. Some trees are also designed to be sterile.

So why do cities prefer to use male plants in certain locations?

Male trees are cleaner and easier to manage than female trees. Unlike their female counterparts, distinctly male plants produce pollen but do not produce seeds, pods and fruit, which fall to the ground and create mess. Female trees also attract pests, including bees, because they provide a source of food.

So foresters and landscapers in North America started using predominantly male trees around 1950 in parks, along streets and in other public spaces where falling fruit could be a problem.

Get weekly health news

Tom Ogren, a horticulturalist from San Luis Obispo, Calif., says this type of unnatural selection in cities has contributed to rising pollen levels and exasperated allergies and asthma. Cities also purchase cultivars specifically marketed as “podless” or “seedless,” he said.

“There’s almost nothing natural about how those trees came to be,” Ogren said. “They call it nature, but nature is balanced.”

WATCH: Why some people get hay fever and others don’t

He calls this “botanical sexism.”

“There’s probably a hundred different cultivars just of honey locusts alone in the trade, and every single one of them is pod-free — in other words, they’re all males now,” he said.

What are Canadian cities doing?

Rob Oliphant, a Liberal MP for the Toronto-area riding of Don Valley West and the former president of Asthma Canada, says cities have a responsibility to consider the types of trees they use.

He also says the federal government needs to ensure Canadians understand the day-to-day effects of climate change and that increased pollen is a public health risk.

Oliphant cites a 2014 paper from Georgetown University law professor Brian Sawers that calls for stricter regulation of allergenic plants.

Like Sawers, Oliphant believes suffering caused by pollen allergies is largely a human creation.

“If you can’t breathe, nothing else matters,” he said.

So what are Canadian cities doing in the fight against asthma and allergy-inducing pollen?

Many cities across Canada said they rely on species of trees and shrubs that are both male and female. They do, however, use male trees in certain locations.

Neither Toronto nor Ottawa considers the sex of trees when planting. Ottawa will look at addressing plant-related allergies in its urban forest plan beginning in 2022, while Toronto said it relies heavily on native and monoecious tree species because they’re low-cost and boost local ecosystems.

Hamilton, meanwhile, has adopted a more allergy-friendly planting policy. Trees identified as “high” pollen producers have been removed from the city’s list of approved species.

WATCH: Allergy season is back in full force due to shifting climate patterns

The Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board has also adopted an “allergy-friendly” planting policy that encourages schools not to use highly allergenic plants, such as male juniper and mulberry bushes.

Halifax’s forestry plan calls for native species to be used. The city still plants male-only trees in certain locations but says recent interest in botanical sexism and species diversification has resulted in fewer cultivars being planted in favour of “true” species.

Other cities, such as Calgary, Regina and Winnipeg, said their main concern when deciding what trees to select is heartiness — whether they’ll survive the winter. The cities also commented on the limited supply of female trees available through Canadian nurseries.

Edmonton, meanwhile, has started its own nursery and grows roughly 10 per cent of its annual tree stock, with a goal of reaching 50 per cent within the next decade.

Melissa Campbell, Edmonton’s forestry supervisor, said the city decided decades ago to plant seedless trees after complaints from residents. But this has slowly changed, she said.

“The emphasis on selecting species is more on diversifying the urban forest and planting the right tree in the right location,” Campbell said.

Vancouver also prohibits some species of highly allergenic trees in public spaces. But the city doesn’t have a policy when it comes to planting male or female trees. A spokesperson said many of the trees planted along streets are male, while some have “complete flowers” with both male and female sex organs that are engineered to be sterile.

Victoria has started considering allergies when selecting plant species for certain locations, such as playgrounds.

Science in the fight against allergies and asthma

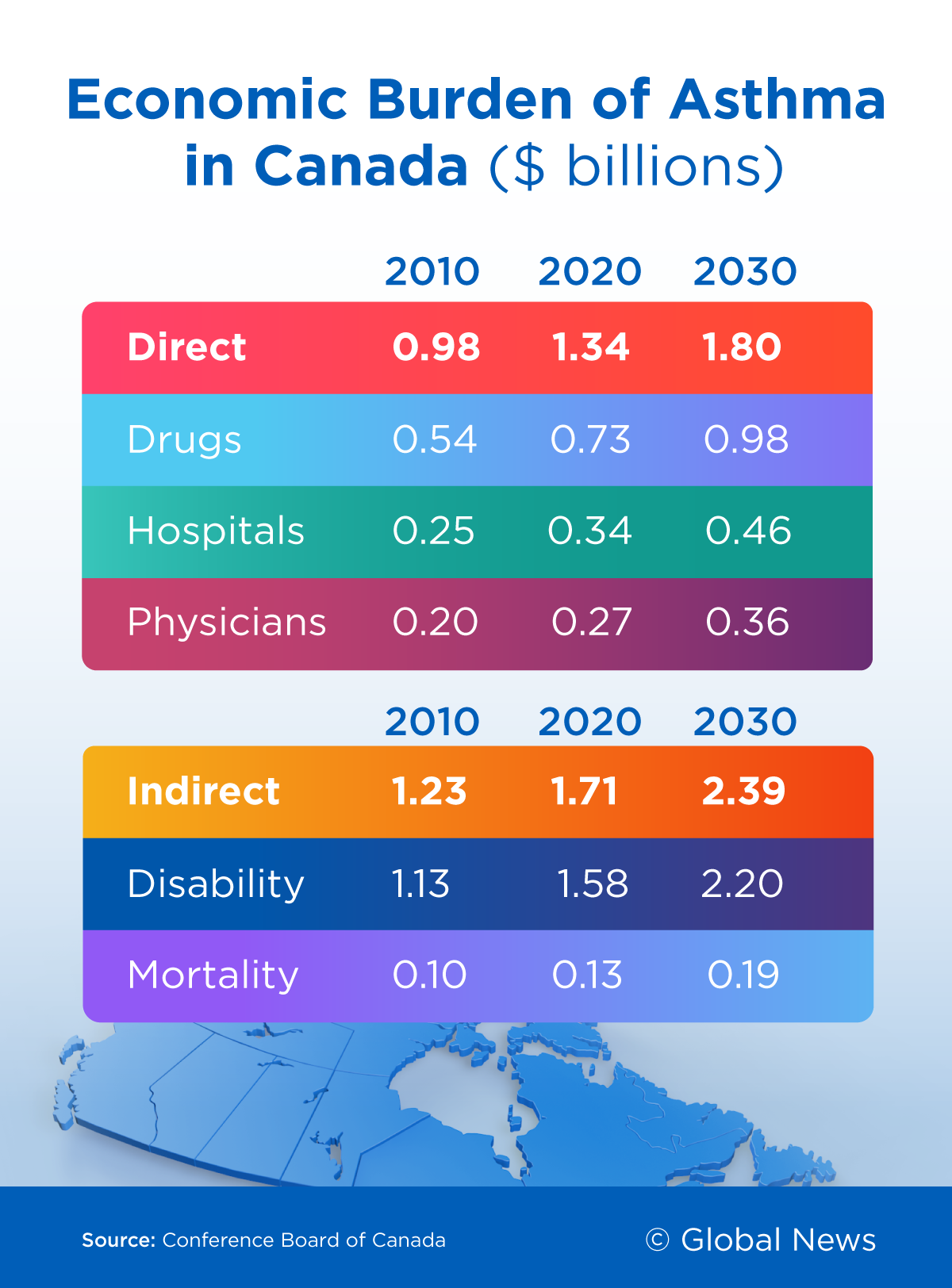

The Conference Board of Canada says the cost of treating asthma in Canada was roughly $2.2 billion in 2010. This is expected to rise to $4.2 billion by 2030, with roughly half the money going toward long-term disability payments.

Research from the Canadian Institute for Health Information also shows that asthma attacks are a major cause of hospitalization. In 2015, asthma resulted in more than 70,000 trips to the emergency room and was attributed in the deaths of roughly 250 people.

Ken Farr is a dendrologist, a scientist who studies trees, for Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). Like Ogren, he believes urban foresters can be better at creating balanced green spaces and selecting plants that do not exasperate respiratory illnesses and allergies.

“If you look at pollen under a scanning electron microscope, they’re like little spiky balls,” he said. “They’re really quite nasty, and you can understand why it is so irritating.”

While planting more female trees would be a great start, Farr said, certain tree species — primarily conifers, such as pines, firs and some varieties of spruce — evolved before insects were around to pollinate. As a result, these trees are big-time pollen producers, using the wind to fertilize as large an area as possible.

“One hundred kilometres of travel is not impossible for pollen,” he said.

WATCH: New Jersey ‘pollen bomb’ video demonstrates how bad pollen can be

Other Canadian researchers agree that having balanced green spaces is important.

Eric Lavigne is a senior epidemiologist at Health Canada. He says the government recently launched two projects to help scientists better understand how urban forests work and how they affect people’s overall health.

The first of these projects started last year and measures specific tree and shrub pollens in Toronto. The second project starts in July and will use satellites to gather information on the types of trees in urban forests across the country.

Data from these projects will be shared with physicians, ecologists and urban planners, who will then use the information to study everything from how pollen affects women during pregnancy to what types of plants can be used to better mitigate air pollution in cities, Lavigne said.

Climate change and pollen

Pollen from trees and shrubs isn’t the only contributor to allergies and asthma. Grasses and certain weeds also produce significant amounts of pollen that fuel respiratory illnesses.

Dawn Jurgens and Daniel Coates with Aerobiology, a company that monitors pollen levels across Canada, say cities from Victoria to Montreal have seen significant pollen increases over the past fifteen years.

“Major metropolitan areas seem to be seeing elevated pollen or more total annual pollen,” Coates said.

But this isn’t happening everywhere, Jurgens said. Some smaller, more rural communities have seen less significant increases in pollen. Jurgens can’t explain the difference between large and small communities but says local weather — how much it rains and how warm it is — plays a significant role in pollen production.

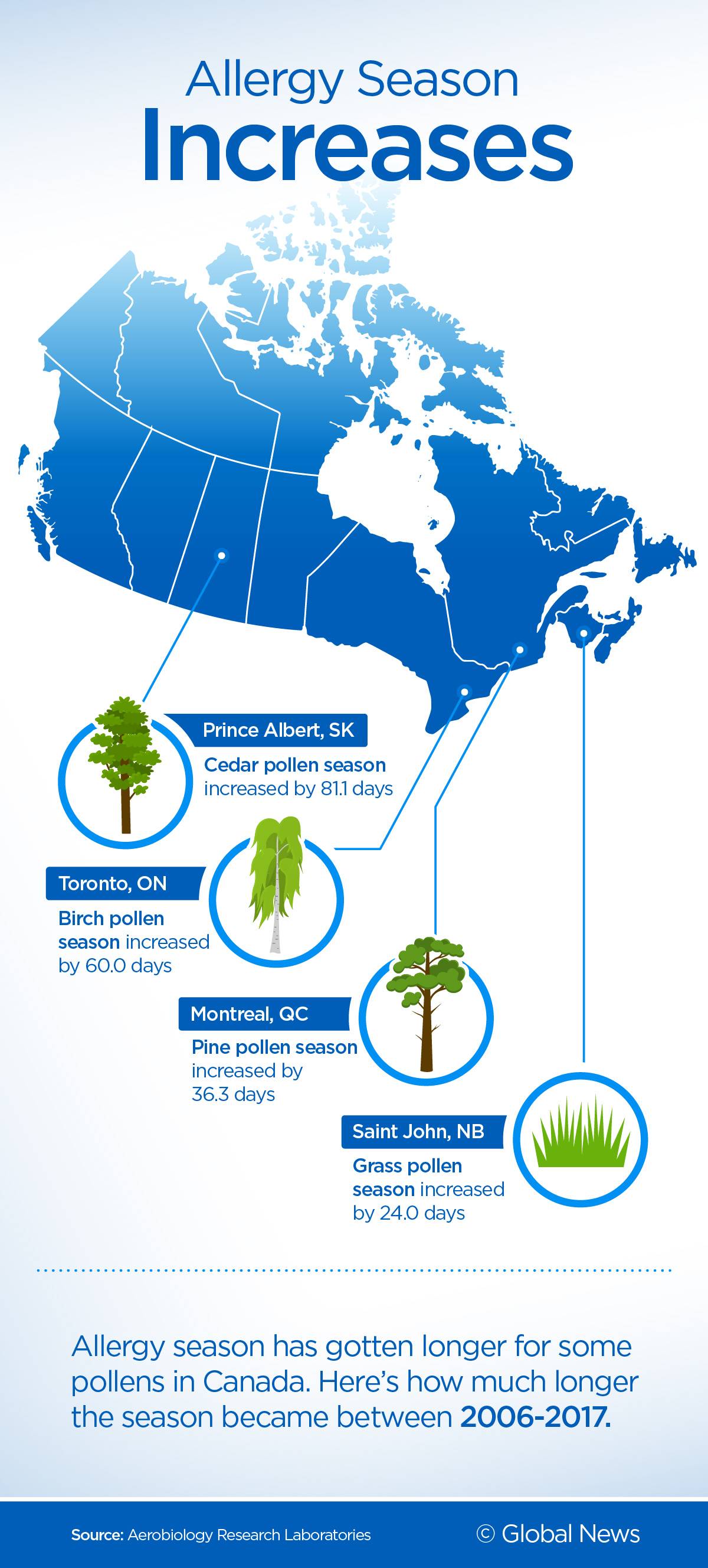

This same phenomenon is being observed in the United States, where research has shown big spikes in certain types of pollen and extended allergy seasons stretching from Winnipeg to Texas.

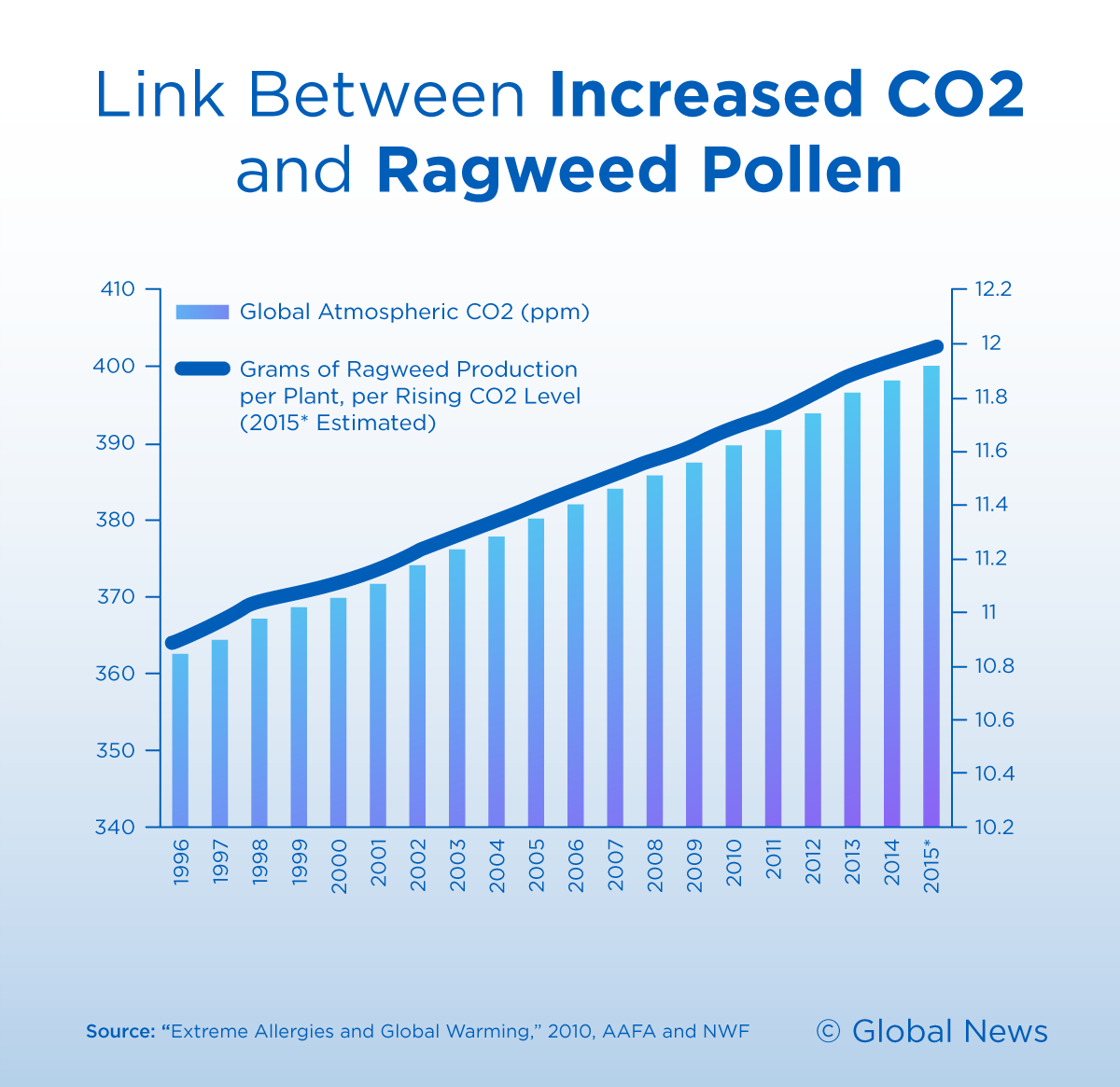

For example, a report from the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA) showed ragweed pollen season has increased by as much as 25 days a year in certain parts of North America. The AAFA has also published reports showing that as carbon dioxide levels rise so does the amount of ragweed pollen in the air.

Angel Waldron, a spokesperson for the AAFA, says the effects of climate change on asthma and allergy sufferers can no longer be denied. She points to massive pollen plumes in some U.S. cities as examples of how a warming planet has contributed to rising allergy levels.

“I remember growing up, you didn’t have 40 million people suffering from allergies every year,” she said. “Warmer temperatures allow trees, grass and weeds to pollinate for months. They pollinate stronger and they pollinate longer.”

While botanical sexism hasn’t been the organization’s top priority, Waldron believes urban planners can be better at finding ways to do their jobs while still protecting the communities they serve.

“Focusing on male trees is definitely an issue — and not a good one,” she said.

It’s a sentiment Ogren agrees with. When he started his quest to make urban forests more allergy-friendly, he said few people were interested. In fact, he said some people thought he was “anti-tree” or out to kill local green spaces.

But now, nearly 35 years later, he says he’s feeling far more optimistic. His local hospital, which he admits he had previously trashed in the media for its less-than-favourable tree selections, recently hired him as a consultant to make the grounds “certified allergy-friendly.”

“I want some consideration for all those people out there that have allergies or asthma,” he said. “I don’t see how that should be such an outrageous concept.”

Comments