Shully Sappire works two jobs. That’s one more than would be ideal but still two less than what she used to work to pay her bills. Some days, the 22-year-old from Nigeria rolls out of bed and works a “normal” 9-5 doing social work and legal intake in downtown Toronto. Other days, she sleeps late, clocking in at 4 p.m. for a bartending shift. The goal is one full-time job — preferably in the legal field — with benefits; it’s not yet in reach.

So, Sappire, who has chronic health issues and struggles to pay her bills even with two jobs, plays mental gymnastics when she’s sick: if I stay home today, what if it’s worse tomorrow and I can’t afford a second day off? But what if the only reason I need to stay home tomorrow is because I went to work today? Am I sick enough that I need to go to the doctor? Is there any point if I can’t pay for the medicine the doctor will prescribe me? Do I muscle through the pain?

Second-guessing, Sappire says, is second nature.

“It’s hard when you are using a body to do things on a daily basis and you’re also fighting that body on a daily basis.”

At a time when there’s never been more information about how to live a healthy lifestyle, Canadian obesity rates are twice as high as they were in the 1970s and Canadians are also increasingly suffering from chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes. Global News is looking at what’s going on, and why knowledge isn’t enough.

For a growing number of people like Sappire, the problem boils down to money.

“The poverty story is quite simple,” says Daniele Zanotti, president and CEO of United Way Greater Toronto. “Poverty negatively impacts health in both visible and invisible ways.”

Here, it’s visible: Canada spends billions every year treating chronic diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and some forms of cancer. Here, less so: Sappire seems like any other young adult, grabbing a quick coffee during her morning commute.

Except that with two part-time jobs and no benefits, staying healthy is hard.

For a few years, as an international student at the University of Toronto, Sappire had access to medical help. She had a doctor and she had prescriptions, although no clear diagnosis for her chronic health concerns. In addition to mental health struggles, Sappire suffers from migraines and vertigo and other chronic issues that have yet to be formally diagnosed.

There was one drug, she says, that dulled her symptoms, that made it possible to keep functioning through the pain. But she had to abruptly stop taking it when her student coverage ran out after graduation. Sappire tried to ease her own withdrawal symptoms, even asking the pharmacist if she could pay for just one or two more pills. She remembers the pharmacist laughing at the request.

Now, Sappire tries to wait out the pain.

“I’ve gotten really used to dealing with difficult episodes,” she says, “I usually see how long it lasts and how intense it is.”

Sappire’s struggles are regrettably common, Zanotti says.

It’s estimated that one in five Canadians work similarly precarious jobs. That statistic jumps to 40 per cent in the Greater Toronto Area, per United Way’s research. An Ipsos poll conducted for Global News last month found young people’s mental health is also directly linked to their work and finances.

Sixty per cent of millennials surveyed said their finances had an impact, while 63 per cent said their jobs played a part. The more stressed or struggling a person was, the more likely they were to list work and finances as stressors.

Get weekly health news

Worrying so much about where your next paycheque is coming from has hugely negative impacts not just for people’s mental health but physical health as well, Zanotti says.

“Things are only going to get worse.”

***

When Valerie Tarasuk started researching issues with food access in the 1980s, food banks were newly operational. The idea, says Tarasuk — now a professor in the University of Toronto’s nutritional sciences department and principal investigator on PROOF, a team that researches household food insecurity — was to give people “a little bit of help” in a moment of crisis.

The problem, she says, is “the crisis never stopped.”

WATCH: Food banks struggling to fulfill the growing need

So much so that in the Canadian poverty reduction strategy released last month, food insecurity is listed as an indicator by which the federal government intends to track its progress. The issue is so widespread, Tarasuk says, that more than four million Canadians are affected. That’s one in every eight homes.

“The people living in food-insecure households don’t have the same options to eat healthy as other people,” she says.

“You’re struggling to get not just a balanced meal but you’re struggling to get enough food.”

Research, including that from PROOF, has linked food insecurity with a whole host of health issues:

- A greater prevalence of chronic issues, such as:

- Stomach or intestinal ulcers

- Mood/anxiety disorders

- Migraines

- Hypertension

- Heart disease

- Diabetes

- Bowel disorders

- Back problems

- Arthritis

- Asthma

- A greater risk of:

- Suicidal thoughts

- Depressive thoughts

- A major depressive episode

- A mood disorder diagnosis

- An anxiety disorder diagnosis

- It exacerbates difficulties in managing conditions like diabetes and HIV

- For kids, it leaves a mark. They grow up facing greater risks of:

- Asthma

- Depression

- Suicidal ideation as adolescents or young adults

***

Nearly half of adults between the ages of 18 and 54 said they’ve had to choose between buying healthy food and paying their utility bills or buying medicine, according to the Ipsos poll conducted for Global News. That figure dropped down to 37 per cent for those aged 55 or older.

That makes heartbreaking sense to Lori Nikkel, CEO of Second Harvest.

As Canada’s largest food rescue organization, Second Harvest picks up surplus food that would otherwise be tossed away and delivers it to organizations that need it. But that’s not a long-term solution, Nikkel says, because it doesn’t solve the issues that make buying healthy food such a struggle.

“Food security is not about food, food security is about income,” she says. “People need to be paid properly. We need to have access to good jobs. We need affordable housing.”

It’s an issue “bubbling under the surface all the time,” U of T professor Tarasuk says.

Although the issue rated mention on the federal poverty reduction strategy and Canada’s chief public health officer acknowledges its extreme importance, Tarasuk says people still don’t seem to have “grasped the urgency.”

“We’re constantly hearing bemoaning about health-care spending and how it’s got to come down,” she says. “Well, this is a modifiable risk factor if there ever was one.”

The problem, says Leslie Boehm, is that addressing those issues doesn’t yield quick, politically friendly results.

“It’s dramatic to do illness care: you’re ill, you’re cured. Everybody can see that,” says Boehm, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation.

“The issue is if you start trying to prevent things, it can take years to realize the results, you know, a kid eating properly and not getting diabetes. There’s no dramatic event … the politicians can’t run around and take credit.”

Sappire doesn’t know what the broader solution is or what the policy changes that might actually make a difference would or could be. What she does know is that in their absence, people seem to shove all the responsibility onto the shoulders of people like her who are struggling to do their best.

WATCH: Federal government unveils poverty reduction plan

Sappire considers herself one of the fortunate ones: she is mobile and has access to numerous services simply because she’s in downtown Toronto. Her parents, back home in Nigeria, chip in to help cover her rent.

But even though she’s careful, even though she’s constantly evaluating and second-guessing her decisions, Sappire says there’s no shortage of wealthier people there to tell her she’s doing it wrong.

“When you have a higher income, people don’t really question what you do with your money,” she says. “But when you’re the lower-income person, suddenly people feel like they can tell you what you should be spending your money on.”

Exclusive Global News Ipsos polls are protected by copyright. The information and/or data may only be rebroadcast or republished with full and proper credit and attribution to “Global News Ipsos.”

This Ipsos poll on behalf of Global News was an online survey of 1,001 Canadians conducted between Aug. 20-23. The results were weighted to better reflect the composition of the adult Canadian population, according to census data. The precision of Ipsos online polls is measured using a credibility interval. In this case, the poll is considered accurate to within plus or minus 3.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

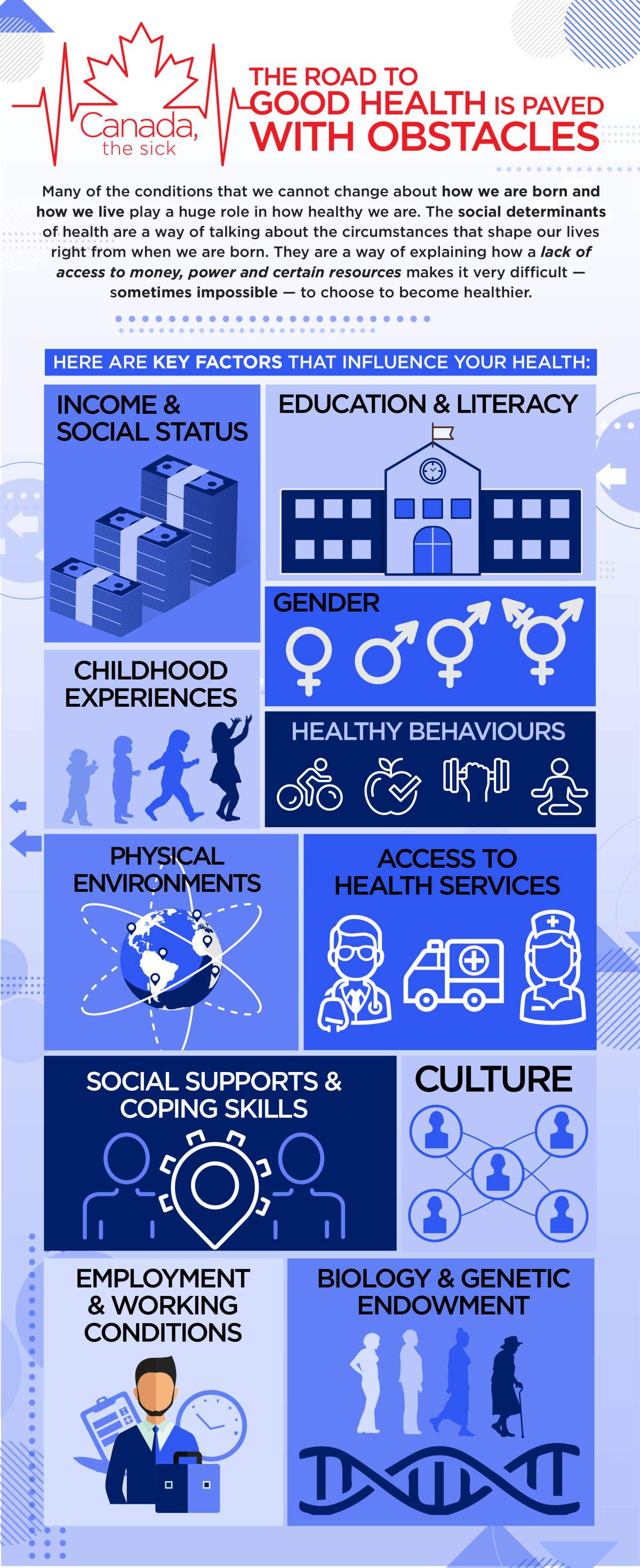

![A few years ago, the Canadian Institution for Health Information’s (CIHI) population health initiative wanted to see just how persistent health inequality is in Canada and dug into the gap, comparing Canada’s richest and poorest using 16 health indicators including obesity rates.“We’ve really seen that these gaps are large and they’re not changing over time,” says Erin Pichora, program lead with CIHI’s population health initiative.“We’ve tried to highlight interventions that could address these inequalities so different programs and policies that might help target low-income populations.”That work is ongoing.WATCH: Canada’s chief public health officer explains what contributes to Canada’s high obesity rate[tp_video id=4477773]At this point, Sappire says, she doesn’t make food decisions based on nutritional value but on budget. Her appetite comes and goes depending on how sick she’s feeling and money is too tight to buy fresh produce that will go bad if she gets sick and can’t eat it.She’s gone through various phases: stocking only frozen foods that she can thaw when her appetite comes back, buying groceries on a meal-by-meal basis, or buying her lunches because $6.99 for sushi is cheaper than a bag of groceries that she likely won’t get through if she can only stomach one meal every few days.“Food, although I’d like it to be important, tends to depend on how sick I feel,” Sappire says.](https://globalnews.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/canadasick1.jpg?quality=65&strip=all&w=1200)

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.