This is the fifth and final story of a five-part series on how alternative relationships are reshaping love in Canada. Each day this week, we’ve explored a different union model, from sexless and arranged marriages to mixed orientation and polyamory. Follow along on Twitter with the hashtag #SOTUCanada.

Four years ago, Jill — acting on not much more than a hunch — accessed her husband’s text messages. What she found changed their marriage forever.

Don had been unfaithful. His texts proved it beyond a shadow of a doubt, Jill recalls, but there was a painful layer of complexity: he’d been cheating on her with a man.

READ MORE: How alternative relationships are reshaping love in Canada

Until that moment, Jill had assumed her husband and best friend of nearly 30 years was as straight as she was.

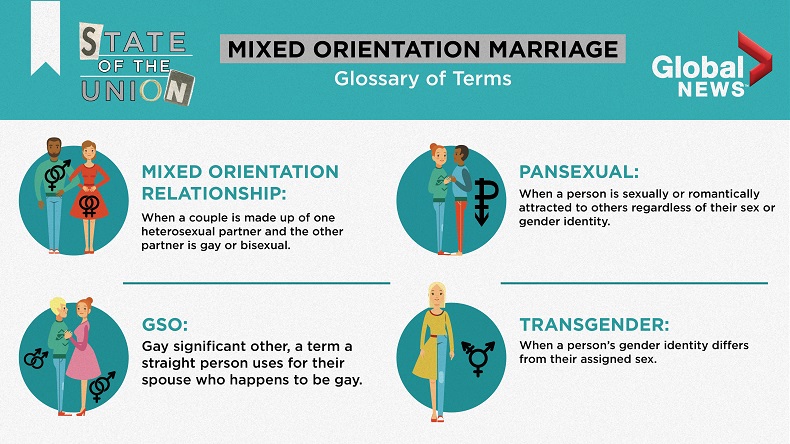

“We’ve always been in a mixed-orientation marriage,” she says. “I just didn’t know.”

Today, the Florida-based couple looks back on that discovery as a pivotal point in their union. After years of repression and confusion, Don finally admitted to himself, and to Jill, that he is bisexual. Jill had to learn to trust him again, and together, they began working toward what they call their “new normal” as husband and wife.

Their mixed-orientation marriage may seem unorthodox, but it’s hardly unique. An increasing number of Americans and Canadians are living openly (or privately) in what they describe as healthy, happy, long-term relationships in which their sexual orientations just happen to differ.

“You think you’re the only person, or the only couple, in the entire world who’s going through this,” says Don, who asked that the couple’s full names not be used for privacy reasons.

“There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of couples who are in this process. You realize, ‘Oh, we’re not such freaks.’”

‘How do we have sex? Google it’

The U.S.-based Straight Spouse Network estimates there are, at a minimum, two million straight Americans who have been or who are married to people identifying as LGBTQ. There are no comparable statistics available in Canada, but anecdotal evidence suggests mixed-orientation unions are definitely present north of the border.

A recent poll conducted by Ipsos on behalf of Global News revealed that two per cent of Canadians say they are in a mixed-orientation relationship (a figure that rises to nine per cent among respondents aged 18 to 34).

Of those, 64 per cent said that it had no impact on their union, while 20 per cent said it made it stronger and 16 per cent said it made it weaker.

Overall public opinion about these partnerships is also mixed. While 57 per cent of Canadians feel that mixed-orientation partnerships are acceptable, 43 per cent say they are not.

Global News heard directly from more than a dozen mixed-orientation couples after putting out a call for people to share their stories.

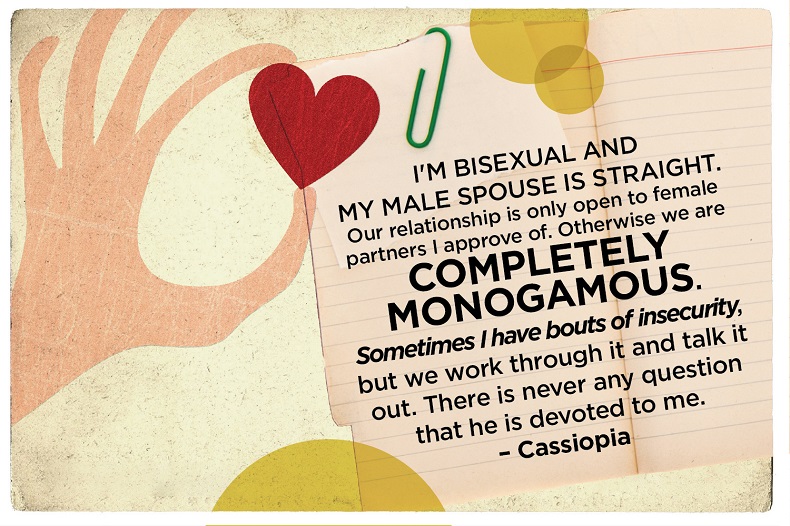

In many of the cases, one spouse or partner identifies as bisexual, like Don, and may have had same-sex partners in the past. But they have ultimately chosen to enter a relationship (or stay in one) with a straight person of the opposite sex.

That was the case for Nicole Menzies, who lives with her straight husband and young daughter on the Prairies. Menzies, 38, identifies as bisexual, and disclosed that to her now-husband as soon as they began dating five years ago. They’ve now been married for three years.

“My sexual orientation has always been something I want to be honest about,” she says.

Get daily National news

“I don’t hide that from my daughter, I don’t hide that from my family. I’m not about to hide it from a potential love interest.”

READ MORE: Do couples living apart hold the secret to everlasting love?

The couple had to have some pretty frank conversations early on, she adds, but it’s now become part of the fabric of their marriage.

“He’s very conservative, so he was like, ‘Does this mean I have to work against two (sexes)?’ And I said, ‘No, my dear. That’s not what you’re going to have to worry about. My heart is with you.’”

Mixed-orientation couples may, like Menzies and her husband, present as 100 per cent heterosexual to the people around them. That leads to a whole new set of questions and misconceptions if, and when, they decide to disclose.

“(People reference) threesomes,” Menzies says, chuckling.

“I wish people would come a little bit more up to speed with that. It kinda gets annoying that the first questions they go to are sex-based questions. They don’t understand how our relationship works … like it can’t be real love.”

READ MORE: Polyamory is a world of ‘infinite’ love. But how do the relationships work?

Enya, a young woman who identifies as pansexual, told Global News that she and her boyfriend Casper, a transgender man, have encountered the same issues. While gender identity and sexual orientation are two very different things, the couple does consider their relationship to be mixed orientation.

“People have come up and asked us about things that are kind of personal,” says Enya, 19.

“You wouldn’t ask someone in a straight relationship how they have sex. That’s not appropriate. I dunno, Google it.”

Casper, who began his transition in high school, agrees. He says the couple is mostly content to let strangers believe they’re straight.

WATCH: Two per cent of Canadians are in a mixed orientation relationship, new Ipsos poll finds.

Meeting in the middle

According to Enya, dating a fellow member of the LGBTQ community has been somewhat easier than dating straight men. She had two past relationships involving straight partners who misunderstood her sexual orientation, or trivialized it.

Menzies encountered similar issues with a previous partner who couldn’t seem to stop randomly bringing up her bisexuality in conversation.

Nick Mulé, associate professor at York University’s School of Social Work, says it can be hard for a non-LGBTQ partner to grasp the nuances of the community — at least at first.

“If, for example, a bisexual partner is actively involved in the LGBTQ community but their straight partner isn’t, there’s going to be a bit of a social separation there. A difference in terms of sensibility, understanding, some of the openness toward sexuality, gender identity, gender expression that is more apparent in the LGBTQ community.”

Couples can sometimes learn to navigate this “if each partner participates in the other’s world,” Mulé adds.

‘Sad scenarios’

Mixed-orientation pairings aren’t always open and transparent, however. Some people enter a marriage to mask, or even try to suppress, their true sexual orientation. Like Don, they may not even be able to put a name to their feelings until later in life.

“It was something that was so deeply buried in me that I didn’t even possibly recognize it,” Don says of his bisexuality.

READ MORE: Sexless marriage can work, ‘sex itself may not be important’

This type of mixed-orientation marriage was more widespread in decades past when LGBTQ people were labelled sick, deviant or even dangerous, says Mulé, but these unions definitely still exist today.

“Many people did marry to ‘do the right thing,’ per se, for public appearances, for acceptance within their family, among neighbours, in workplaces. Those were very sad scenarios, and continue to be.”

Hiding your sexuality from your husband or wife can be incredibly difficult, and for many, the facade inevitably crumbles. A number of online groups and chat rooms have emerged to help people whose spouses have come out to them as gay, lesbian or bisexual, even after decades together. There are other support groups for the spouses who do the coming out.

“There are some really nice, normal people around the country just like us, that we’ve grown to know and socialize with when we travel,” Jill says, noting that both she and her husband remain actively involved in helping others who are going through a situation similar to their own.

After many discussions and hard work to rebuild trust, Jill and Don say they are now more deeply connected and attracted to each other than ever. They have chosen an open marriage, in which each partner may pursue other relationships, as long as they disclose it. Ultimately, they say, it’s up to each couple to determine how they want to proceed.

Some people may opt to stay together in a mixed-orientation union (be it monogamous or not) while others choose to separate. Some are able to maintain friendships after the split, others find that too painful.

“The support groups say don’t do anything crazy for at least your first year,” Don says.

“Give it time, talk, seek counsellors. A lot of people get so angry, from our Judeo-Christian backgrounds, you know, about how this is such a horrible thing and it’s a sin. They immediately move to the divorce phase. … Our resolve was to stay together.”

Mixed orientation on-screen

Popular culture is slowly catching up to some of these complexities.

The Oscar-winning movie Brokeback Mountain depicted two men secretly falling for each other before each marrying a woman, and the more recent Netflix hit Grace and Frankie offers a highly fictionalized version of what, in reality, would be a similarly thorny situation.

The show features two older female characters who must suddenly confront the fact that their husbands are in love and want to get married. After the heterosexual couples split (spoiler alert), not everyone finds it easy to let go of the connection or physical intimacy they once shared with their ex-spouses.

Mulé says he’s glad to see some of these characters appear on the big and small screens.

“I think it’s helpful. I think it’s encouraging that popular culture starts to recognize that these relationships do exist, that these challenges in people’s personal lives exist.”

According to Menzies, there’s still a need for even more education and awareness surrounding mixed-orientation marriages like her own, which involve two partners going in with eyes open.

“We’re getting there,” she says. “I definitely think there needs to be more out there about it. … (Being mixed-orientation) doesn’t make that marriage, or relationship, less full of love.”

This week, Global News looked at alternative unions. To continue the conversation, follow along on Twitter with the hashtag #SOTUCanada.

The statistics referred to above were drawn from an Ipsos poll conducted between July 13 and 16, 2018, on behalf of Global News. For this survey, a sample of 1,501 Canadians aged 18+ was interviewed online via the Ipsos I-Say panel and non-panel sources. Quota sampling and weighting were employed to balance demographics to ensure that the sample’s composition reflects that of the adult population according to Census data and to provide results intended to approximate the sample universe. The precision of Ipsos online polls is measured using a credibility interval. In this case, the poll is accurate to within ±3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20, had all Canadian adults been polled.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.