Milena Canning can see the steam rising from a cup of coffee. But she might not see the cup.

Or she can see her daughter’s ponytail bouncing when she walks, but when she turns around, nothing at all.

“She can be sitting right next to me and I’ll say to her, ‘Blink your eyes.’ And then when she starts to do that, I see her eyes blinking and I see her mouth moving when she’s talking to me.”

“I know where her chin and nose is but I don’t see it. I don’t see the full face.”

The 48-year-old woman from Scotland has a rare condition, called Riddoch syndrome, where a person who is otherwise blind can perceive objects in motion – but not if they’re stationary.

So while she might not see her husband sitting across the room, if she asks him to wave, “I see his hand. I see his arm go up and down, but I don’t see him sitting in that chair.”

It began in 1999 when she developed a respiratory infection. It was so severe that she was admitted to hospital and put into an induced coma. Over the course of the 52 days she was under, she suffered several strokes.

When she woke up, she realized she had lost her eyesight.

“As soon as I woke up, I actually shouted for my mom first and then my husband, and I did say to them, ‘I can’t see!’”

It was a scary experience, but a few months after she went home, she started to notice a change.

For her wedding anniversary, someone brought her a gift, sitting in a shiny gift bag. “As they put it down, I said, ‘Oh, what’s that there? I think I can see some colour.’”

She told the party she could see something green. “Everything just went silent. Nobody said anything because they thought I was imagining it. It was the gift bag someone had brought.”

Get weekly health news

She went to the doctors – she happened to be working for an ophthalmologist before she got ill – and they told her that her eyes were fine. But, they didn’t believe that she had suddenly begun seeing again after her stroke.

Finally, she got in touch with an ophthalmologist who had heard of cases where people could see only moving objects, and by chance, he mentioned her case to a group of researchers from Canada’s Western University at a conference.

They jumped at the chance to study Canning, and she agreed. “I think because they believed me. They believed in me.”

After years of tests and brain scans, the researchers finally published their results in May in the journal Neuropsychologia.

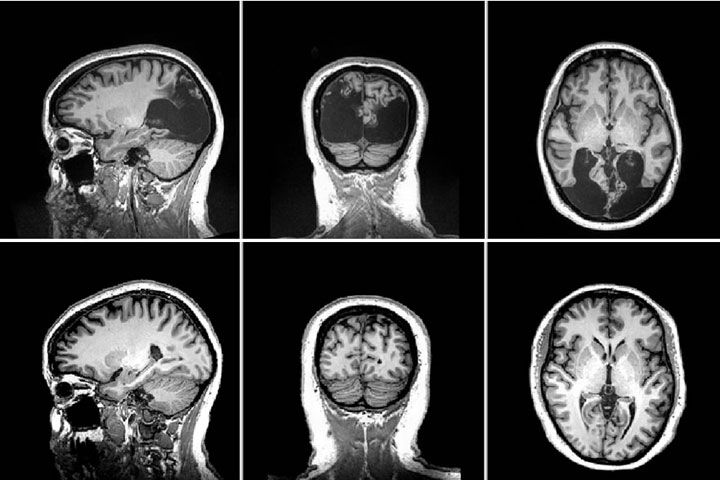

“With the functional MRI, we saw that even though she had some big holes in her brain about the size of a tennis ball in the parts of the brain that normally would process vision, there was still some tissue left in an area that responds to motion,” said Jody Culham, a neuropsychologist and professor at Western’s Brain and Mind Institute.

Essentially, the strokes had killed the parts of Canning’s brain that are used to understand visual information. But, they left intact parts that understand motion. So, over time, her brain learned to process some visual information using what she has left.

“What we think has happened is that there’s some kind of side roads where visual information can also get into the brain and these side roads seem to have been preserved, perhaps even enhanced,” said Culham. So Canning can still get enough information to help her navigate a room or reach for objects.

The Scottish ophthalmologist’s recommendation to sit in a rocking chair, or take horseback riding lessons for the visually-impaired may have helped Canning’s brain make these connections, Culham thinks.

WATCH: Video posted by Western University about Canning’s case

And Canning’s vision has continued to improve. Looking around her living room during a telephone interview with Global News, she said that she was able to see the outlines of her coffee cup and remote control if she was close and stared intensely at them. “Over the years, they have discovered as well that I’m seeing outlines of things that are stationary as well.”

“It’s crazy what I can see and it’s frustrating what I can’t see.”

She hopes that she regains even more vision, but she’s happy that she now has some idea of what was causing her problems. “Thank goodness for the Canadians because I would have been totally in the dark.”

Her case sheds light on how the brain processes visual information and how it adapts to injury, said Culham. “Sometimes, even when one connection, in this case even a big connection is damaged, there seems to be some degree of plasticity where in some cases, other systems can take over.”

“Vision isn’t necessarily an all or none thing. It isn’t necessarily that someone is fully sighted or fully blind but there can be some aspects of vision impaired while others are preserved.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.