Jessica Howe remembers the day her life changed, and the exact feelings and thoughts that ran through her mind. A wave of confusion and fear struck the 40-year-old mom of two one day in April 2015 when her doctor broke the devastating news. Howe had no idea the chronic fatigue she was experiencing, the tingling in her feet and loss of vision would add up to a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

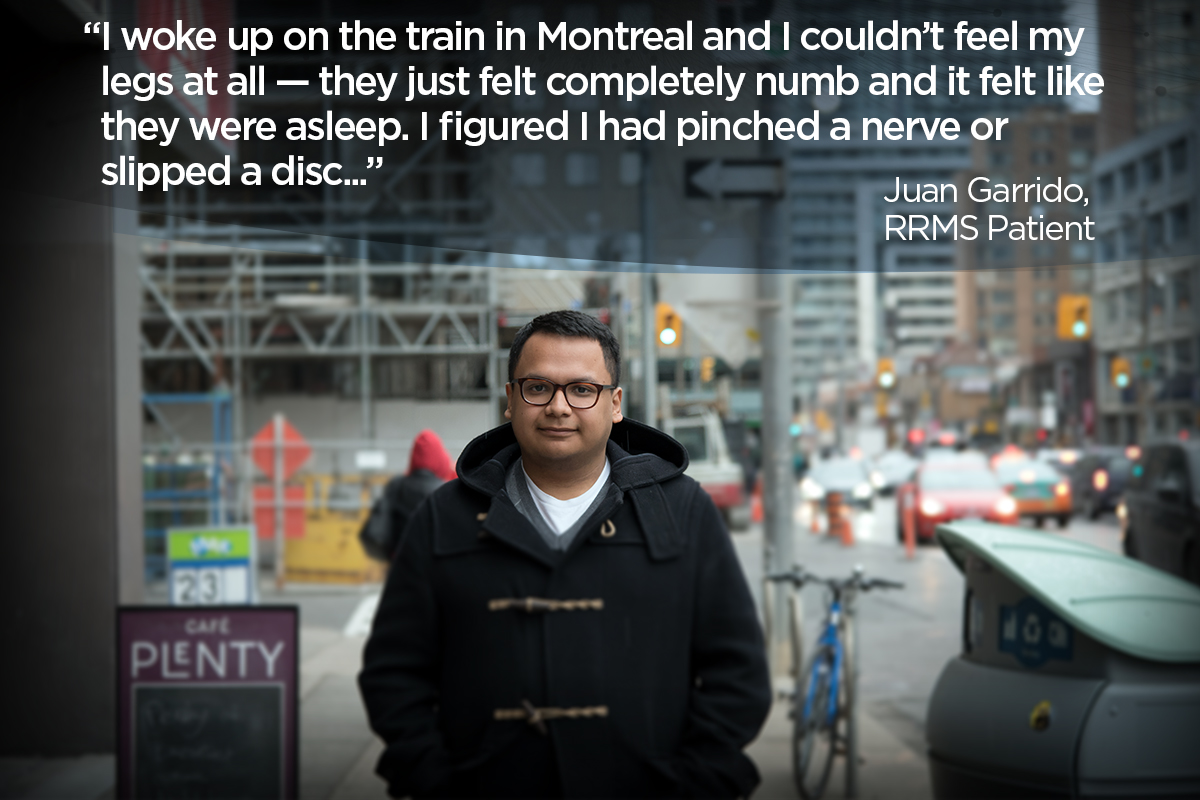

Juan Garrido was on a train when his life took a turn in 2012. The 25-year-old young professional from Guatemala had just finished his first year of university and was on his way back to Toronto from Quebec when he felt tingling — almost like the sensation of a pinched nerve — in the lower half of his body. Weeks later, after experiencing bouts of unbearable fatigue and more tingling in other limbs, he too would get the same devastating news from his physician.

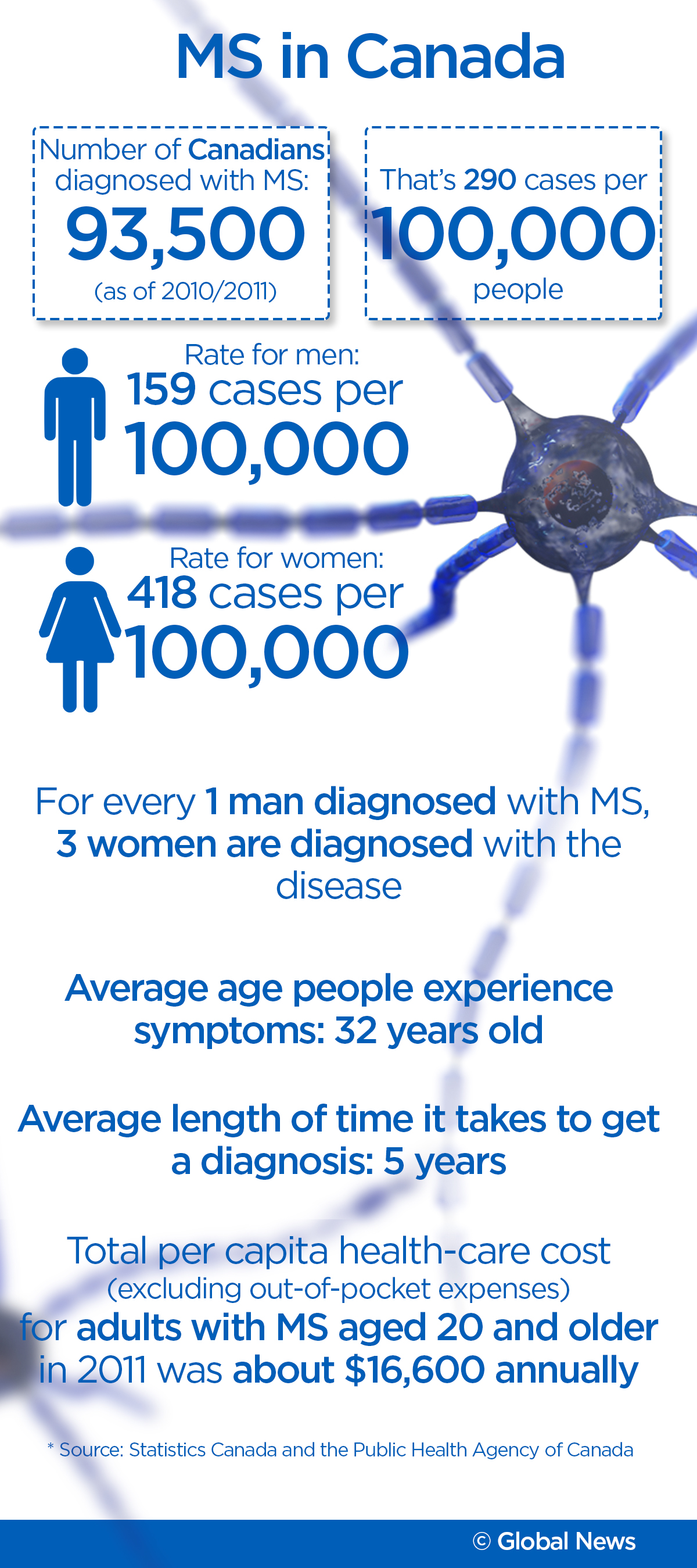

It’s estimated that over 93,500 Canadians of all ages currently live with MS — an inflammatory neurological disease of the central nervous system that impacts one’s brain, spinal cord and optic nerves — and the Public Health Agency of Canada anticipates that number to rise to 133,635 by 2031. Canada is the country with the highest rate of MS in the world, Statistics Canada reports, and while there are theories as to why that is, the ultimate cause of MS remains a mystery.

Understanding MS

Hearing the term “multiple sclerosis” is just as much of a mystery to a newly diagnosed patient as it is to most of the general public. It can be a complicated disease to understand because it isn’t just one event occurring in the body, but rather multiple factors that come together, which result in a list of physical and mental responses.

And it’s that exact confusion Howe and Garrido both experienced when they were diagnosed.

For Howe, her fear didn’t stem from the unknown happening to her, but the unknown of how her children would be affected by their mother having MS.

“Knowing that I’ve just raised their odds to potentially have MS in their lifetime — more so in my daughter because it’s more prevalent in women than it is in men … I have an extreme amount of guilt around that.”

Garrido, on the other hand, did what he could to avoid learning about MS because for him, not knowing brought comfort.

“It was really confusing and scary because I didn’t know what it meant … [The doctor] didn’t really explain what it was or what it would look like, so I really just didn’t know about it at all.”

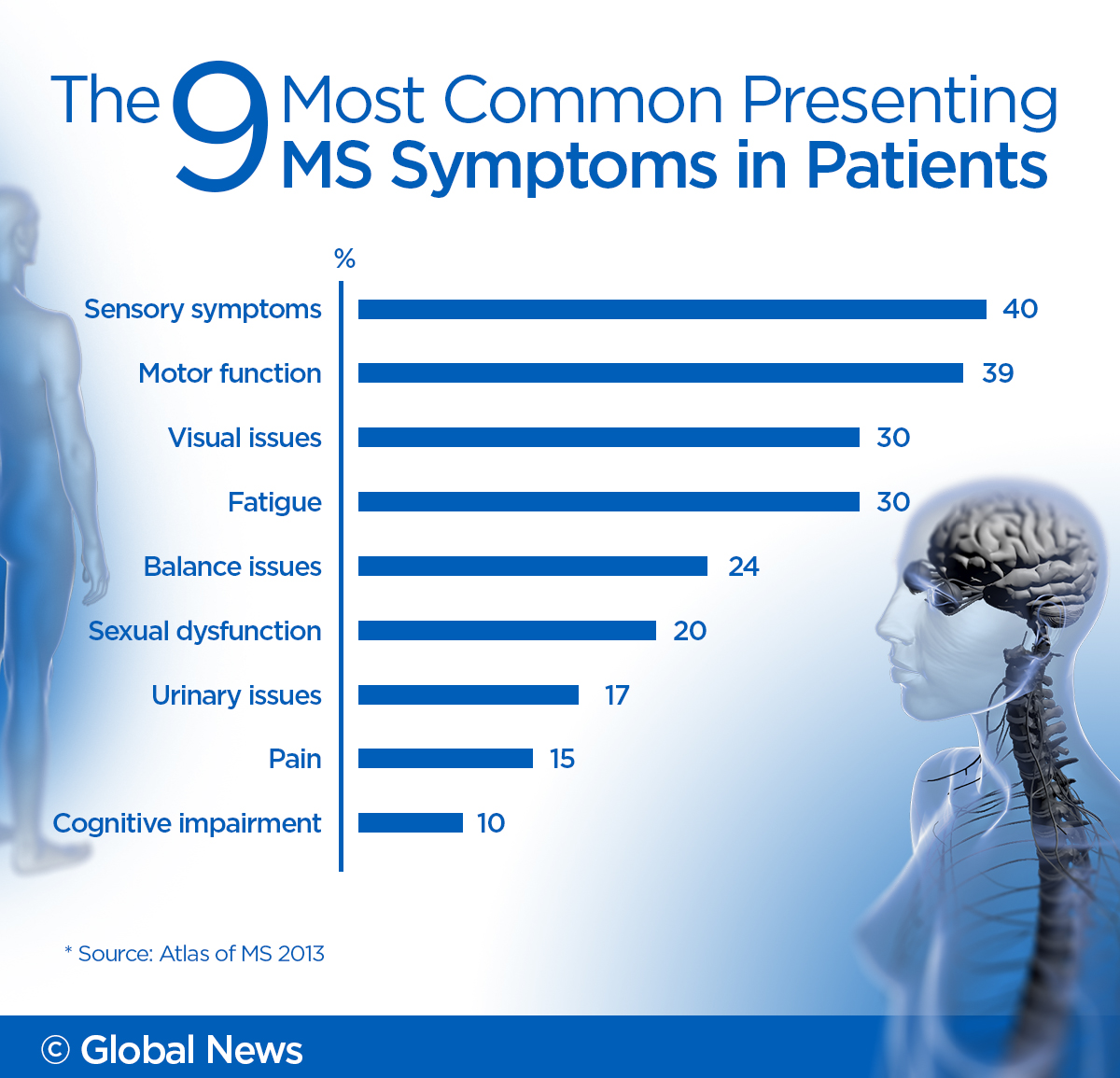

MS has been described by patients and physicians as a “tailor-made disease,” meaning that while many can experience a common list of symptoms, it affects everyone differently and to varying degrees. Flare-ups of symptoms are known as attacks or exacerbations, and the severity and longevity of these attacks vary, lasting anywhere from days to months.

These symptoms manifest as a result of a process of several things happening within the body. To see how MS affects the body, play the video below.

MS is also considered an invisible disease. This is because many of the symptoms experienced by patients are internal and are not always visible to outsiders.

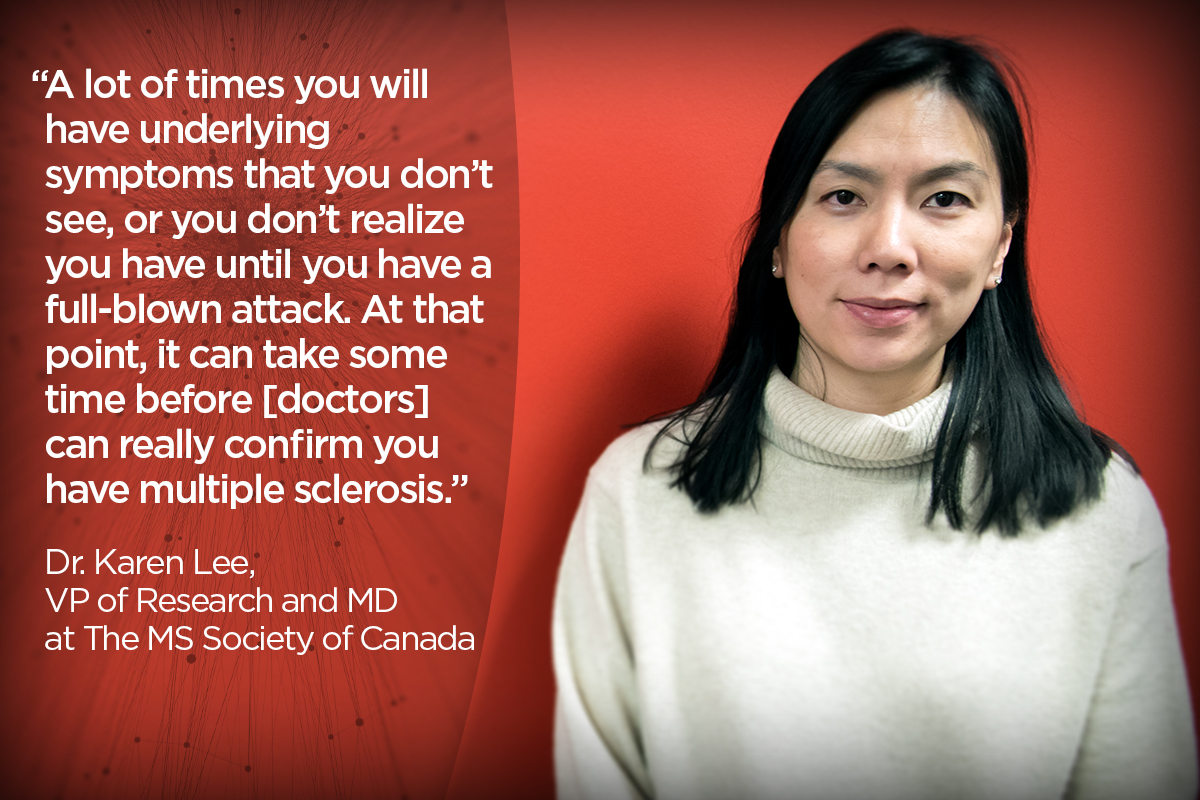

Dr. Karen Lee is the vice-president of research and managing director at the MS Society of Canada. As a disease in people, MS works very much like a lamp does, explains Lee.

First, you have the light bulb, which represents the brain, and the chord, which represents your nerves running into an electrical outlet. Someone who’s healthy would have that chord intact and the electricity running throughout would be able to do so without interruption. Those with MS have unravelled chords, preventing the electricity from moving throughout the body properly.

Visible symptoms, however, are typically seen in patients with more debilitating forms of the disease. They might use a cane or electric wheelchair when their balance is affected.

Other symptoms that can manifest include tremors, temporary hearing loss, gait (like difficulty walking), difficulty swallowing and mental health issues like depression.

WATCH: Dr. Lee discusses why MS can be a difficult disease to diagnose

These symptoms can come on unexpectedly and without warning as attack triggers often differ from patient to patient.

Garrido experienced how unpredictable those attacks can be at Christmas in 2012 when he had to be hospitalized for two days.

“I woke up with numb legs and I kind of felt like I was drunk — so I was dizzy, I couldn’t focus, I was nauseous, I could hardly walk and I spent two weeks just on my mom’s couch because I couldn’t move or walk,” he recounts.

Patients are told to manage their MS through a healthy diet and exercise regime. Some patients may be put on disease-modifying therapies that most often come in the form of pills or injections, Lee says. These treatments are used to slow down the progression of the disease and prevent or limit future attacks.

“We’ve come a long way in the past 20 years,” Lee says. “There were no treatment options for people who live with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), which is the most common form of MS. Today we have 14 disease-modifying therapies on the market.”

There is no cure for MS. While people may die as a result of complications from multiple sclerosis, patients do not directly pass away from multiple sclerosis itself.

The four types of MS

The severity in which people experience the symptoms is related to the type of MS they have. The MS Society of Canada recognizes four different kinds: clinically-isolated syndrome (CIS), which refers to a single episode of neurological symptoms that may suggest MS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) and primary-progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS).

However, RRMS — the type both Howe and Garrido live with — is typically referred to as the technical and first official stage of MS and is most commonly diagnosed. It is often described as unpredictable but is clearly defined by relapses. This is when symptoms appear or existing ones become worse. In between these relapses, recovery is complete or nearly complete to what the body was before remission (the pre-relapse function), the MS Society of Canada explains.

About half of RRMS patients will then go on to develop the second stage, SPMS. Over time the relapses and remissions become less apparent and the disease begins a steady progress of decline with occasional plateaus.

Lastly is PPMS, the most debilitating form of the disease. It is a slow accumulation of disability, the MS Society of Canada explains, and does not come with defined relapses. There may be periods of stabilization and even minor temporary improvement. About 15 per cent of people with MS have this form of the disease, while five per cent of people with PPMS experience some relapse but a steady worsening of the disease from Day 1.

Diagnosing MS in patients

The diagnosis of MS happens a few different ways. The first, Lee says, is by an MRI of the brain and spinal cord to look for plaques (also known as lesions or scars) developing. The plaques are what is responsible for triggering attacks and progressing the disease because they block the signals of nerve cells, which are essential to the body’s functioning.

Another common method today is through a lumbar puncture or spinal tap. Physicians will test the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the tap. Doctors can determine if MS is present if the fluid tests for the presence of certain proteins (antibodies) called oligoclonal bands.

Lastly, there’s an evoked potential (EP) test. In MS, nerve impulses are slowed because of the damage to the myelin coating on the nerves, and an EP test measures and records this slowing of impulses in the central nervous system.

MS can be a difficult disease to diagnose for a few reasons, Lee says. One is that most often the symptoms of MS can mirror other ailments like Lyme disease, lupus and fibromyalgia.

Another reason is the disease’s invisibility.

While the disease can be diagnosed in men and women at any age, the average in Canada is 32 years. Women are more likely to be diagnosed, while men are more likely to experience more debilitating forms of it.

What causes MS to manifest in people is unknown, but researchers have a few theories. Among them is that the disease is hereditary, or perhaps the result of one’s environment or lifestyle, or even a vitamin D deficiency. According to Lee, many also believe that it may be a combination of factors that lead to the development of MS. What that combination is, no one knows for sure.

Canada’s disease and its place in the world

It’s estimated that there are approximately 2.3 million people in the world living with MS, according to the 2013 Atlas of MS, a report prepared by the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Besides Canada, other countries with a high prevalence of MS include the northern U.S., most of northern Europe, New Zealand, southeastern Australia and Israel.

However, MS is also known as “Canada’s disease” among health-care professionals because Canada has had, and continues to have, the highest rate of MS in the world.

Depending on the report the numbers may vary, but according to Statistics Canada’s latest numbers, Canada’s rate of MS sat at 290 cases per 100,000 people in 2010-2011. This far surpasses the United Kingdom, the country with the second-highest prevalence rate of 203 cases per 100,000. Sweden is third at 189.

Considering the cause of MS has yet to be determined, doctors aren’t sure why Canada’s prevalence is so high compared to other countries.

WATCH: Does a lack of vitamin D play a role in higher rates of MS in Canada?

But as the number of Canadians living with MS is expected to grow, there is a need for a better understanding through more research — whether it’s to find a cure or — at the very least — to find more effective disease-modifying therapies for all stages of MS.

And it’s what patients like Howe and Garrido hope will be achieved in their lifetime.

Part 2 of Brain Interrupted, our series on multiple sclerosis, will be published May 15 at 6 a.m.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.