It’s one of the most alarming family justice cases in Canadian history: A high-conflict custody battle with allegations of sexual abuse by a father and incompetence by B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) that raises serious questions about how our system deals with families at their breaking point.

In a five-part CKNW special investigation, reporter Charmaine de Silva takes an in-depth look at how a judge, a lawyer and our system, in general, led to justice being derailed.

In August, B.C.’s highest court delivered a stunning reversal of a lower court decision that found the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) allowed a father to sexually abuse his kids.

The court found one judge, presiding over two separate but connected cases, relied on the evidence of a fraudulent expert to not only tear four children away from their father, but to malign the reputations of psychologists, social workers, and the children’s ministry itself.

From the moment B.C. Supreme Court Justice Paul Walker delivered his July 2015 blow to MCFD, the story of J.P., her ex-husband B.G. (whose full names cannot be revealed because of a publication ban) and their four children has gripped people’s attention across the province.

The ruling was explosive.

How could MCFD social workers allow a father, whom the courts decided had sexually abused his older kids, to have unsupervised access to his youngest child — a toddler, no less?

Why were some of these social workers still on the province’s payroll?

Then came the bombshell decision by the BC Court of Appeal in August of this year.

B.C.’s highest court tossed out the civil action that found wrongdoing by MCFD social workers and ordered a new family trial – raising serious questions about evidence accepted at trial, the judge’s fact-finding ability, access to justice and overall system fairness.

In a scathing decision, B.C. Court of Appeal Justice Daphne Smith called the results of the previous trials – one a family case and the other a civil action against the province – “miscarriages of justice.”

TIMELINE: The longest child welfare, civil litigation in the history of Canada

Unreliable evidence

While multiple experts had questioned the sex abuse allegations and raised concerns about the mental health of the mother in the case, Justice Walker dismissed those opinions.

Meanwhile, he gave weight to a so-called “expert” the mother had found on the internet, one who the appellate court later found had received her credentials from online “degree factories,” and appeared on daytime talk programs such as The Montel Williams Show.

The “expert” had never interviewed the children or their father.

What’s more, because Walker presided over both cases, he chose to carry evidence – later found to be problematic — from the family trial into the ensuing civil trial.

Conflict begins

Get breaking National news

J.P. and B.G.’s marriage began to disintegrate in 2009. The pair have four children, the youngest of whom was a toddler at the time.

In October of that year, after J.P. reported an alleged assault, the father was arrested and removed from the family home.

The case was already on the MCFD’s radar, following several reports – including one from the kids’ vice principal – expressing concern about the children’s safety and J.P.’s mental health.

Nearly two months later, J.P. called 911 again, this time twice in one day. On the second call, she reported she believed her husband had sexually abused their youngest child back in September.

Vancouver police and the MCFD each opened their own investigations into the claims.

But health and social workers also logged their own concerns about J.P.’s behaviour. At one point, B.C. Children’s Hospital staff called security after seeing her appear “manic and disorganized.”

J.P. also created video and audio recordings of the children, who – in response to her questions – disclosed the alleged sexual abuse.

On Christmas Day 2009, she emailed the recordings to at least 20 people, including family, friends and service providers.

Around this time, police and social workers also expressed concerns over her mental health, warning she might run away with the kids or try to kill them and herself.

By the end of the month, the children were removed from their home and placed in the care of another family.

Experts weigh in

In the run-up to the trial, the ministry tasked a psychologist with assessing the couple’s parenting abilities.

He raised concerns the mother had a “mixed personality condition” linked to suspicious thinking and manipulation and found she wasn’t fully up to the emotional and psychological task of parenting.

The same expert found the father did have those capabilities, and that it was unlikely he had sexually abused the children.

Justice Walker then ordered a second expert to assess the family, who also found insufficient evidence of abuse, but suggested counselling could make B.G. a better father.

He also said the mother’s access should be supervised.

Family trial

In 2011, two years after the original 911 call, the case goes to trial.

The father, without money for a lawyer or access to legal aid, represented himself. The mother retained well-known family lawyer Jack Hittrich.

After an unprecedented 91-day family trial, Justice Walker ruled in favour of the mother, rejecting concerns about her mental health and granting her sole custody.

He also ruled B.G. had both physically abused J.P. and her three eldest children, and that he had sexually abused the three kids as well.

In response, he issued a pair of orders barring the father from having any contact with the family or any direct or indirect access to the kids.

Mother sues the province

Following her resounding family trial win, J.P. filed a civil suit against the province, claiming bad faith and wrong-doing on the part of the MCFD.

More troubling, she claimed the ministry had ignored an earlier judicial order barring B.G. from having unsupervised access to the children, allowing him to then sexually abuse the youngest child.

In a bid to be more efficient, Justice Walker also presided over the second trial, rolling many of his findings of fact from the family trial into the new case.

The father was not named in the suit, but still had an interest in it and participated — once again representing himself.

The marathon 146-day trial began in April, 2013, and ended with Justice Walker again siding with the mother.

In his shocking ruling, the judge slammed the MCFD for bias against J.P., which he wrote allowed the father to sexually abuse a child by granting him unsupervised access, apparently in violation of a court order.

Walker found the province was liable to the mother, on behalf of the children, for negligence, breach of fiduciary duty and for misfeasance in public office.

He also ruled that one of the lead social workers’ personal hostility to J.P. and closed mind about the abuse allegations led them not to act in the best interest of the children.

WATCH: B.C. Budget 2016: Care for B.C.’s vulnerable children

Judgment sends shock waves across the province

Justice Walker’s ruling landed like a bombshell at a time of heightened scrutiny of the MCFD and amid media coverage of several deaths of youth in government care.

B.C.’s former Representative for Children and Youth (RCY) Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond was particularly vocal on the file, using it as an example of a troubled ministry that was allowing kids to be hurt.

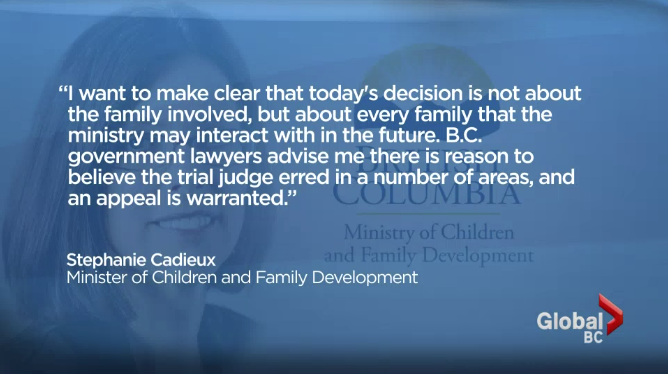

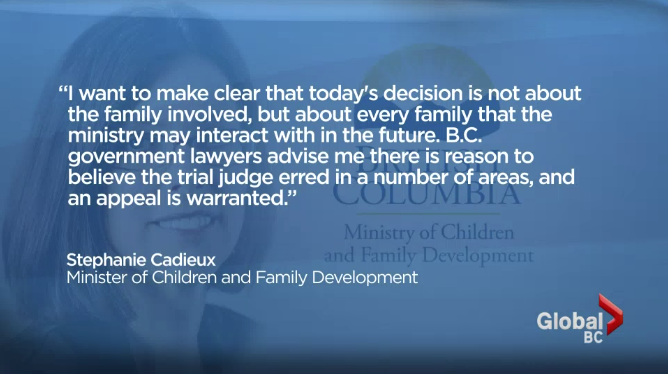

Stephanie Cadieux, the minister responsible at the time, also took heavy criticism — much of it for underfunding the system.

An ensuing government-commissioned report from retired civil servant Bob Plecas found problems with how the MCFD cared for vulnerable kids and recommended more funding.

But it also slammed the RCY, the media and the opposition for creating a “culture of blame.”

But some of the political storm may have been premature.

In August of this year, the B.C. Court of Appeal overturned the case, tossing out almost every damning allegation against the father.

Dec. 2015 Plecas report: MCFD Chronically Underfunded

Aftermath

It has been five years since B.G. has had any contact with his children, who are still living amid the conflict and legal battles.

The case cost millions of tax dollars, consumed nearly a year of court time, tarnished the reputations of social workers and experts and sent the MCFD, already facing resource challenges, into a tailspin.

And it isn’t over. There will either be a new family trial, or it will go to the Supreme Court of Canada, though experts say that’s unlikely.

How did such a damaging case play out with life-altering consequences in a legal system that is meant to have checks and balances?

In this special investigation, CKNW will examine the elements that led to this unprecedented case, including a judge with a track record of ignoring facts, a lawyer and his client who were willing to go to great lengths to win, and a system ill-equipped to best deal with family conflict – is there anything that can be done to prevent more families from having to go through such prolonged life-altering conflict?

READ PART 2: The B.C. judge who ‘ignored evidence,’ ‘erred in law’ and put a ministry under fire

Comments