Is your data ever anonymous?

Companies insist that it is and that it can’t be traced back to you — even as your browsing history, or preferences, can be recorded and analyzed by apps or add-ons in your browser.

But new research suggests that it’s not quite as anonymous as companies suggest.

German journalist Svea Eckert looked into the issue alongside data scientist Andreas Dewes.

In a presentation at hacking conference DefCon this past week, they proved that there are ways to de-anonymize your data.

Eckert started the project to see what information was available on public figures, like politicians.

“We live more and more openly, we live more and more on the web,” Eckert told Global News.

“But the thing is, everything is stored. I mean, if you post something on Facebook, or Twitter, it is there, and it will stay there.”

After posing as a marketing company looking for data, Eckert obtained the browser history of three million German users over a 30-day period.

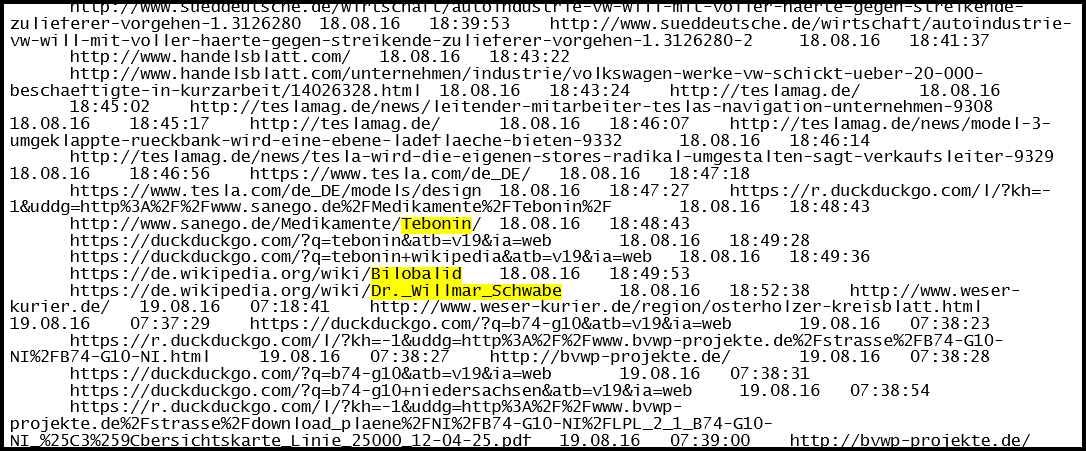

While the data was only associated with an anonymous user ID, it didn’t take long for Eckert and Dewes, to start matching those IDs to the names of some prominent public figures, including politicians.

For example, if a logged-in Twitter user wanted to look at their own Twitter analytics, their user name appears in the URL, which was stored.

Eckert and Dewes compared certain URLs to other data, such as a list of politicians’ Twitter handles.

Get daily National news

Eckert managed to identify Valerie Wilms, a member of the German federal parliament, through this process.

People could also be identified through travel documents, which listed their names in URLs.

Once Eckert had Wilms’ name, she was able to search the browsing history for the politician’s private information, including travel documents and medical and tax info.

“Of course, this can hurt and it leaves people vulnerable for blackmailing,” Wilms told Eckert.

“With only a few domains you can quickly drill down into the data to just a few users,” Dewes told BBC News.

“It’s very, very difficult to de-anonymise it even if you have the intention to do so.”

Where did the data come from?

Eckert said the data she collected was gathered from browser plug-ins – applications that users installs on their browsers that usually provides a service that is helpful.

But many applications and add-ons also store information about your browsing habits anonymously – and send them back to a server where it can be stored for years, Eckert explained.

One of the major providers she got the data from was Web of Trust, an add-on that lets a user know whether a website is safe. After Eckert published her data, it has since updated it’s user policy to indicate it may use “non-personal information” for research and analytics.

The data collected can then be sold or given away for free, as it was to Eckert.

“We had people who had 10, 15 browser extensions,” Eckert explained. “Sometimes they had forgotten about them, but they still had them in the browser.”

She said it’s important to have “internet hygiene” — that means making sure you know what’s on your browser that could be sending data back to a company.

WATCH: Security experts warn computer hacking on the rise

Calls for more protection

There are many ways that this type of information could be used against you, Eckert explained.

While not every company shares the data they store, there’s always the possibility it could be hacked.

“So much data is leaking, is getting hacked,” she said.

More laws need to be enacted to regulate how long these companies can store the data, Eckert argued.

She said there should also be more concrete laws on whether they can gather data in the first place.

In the European Union, The General Data Protection Regulation law is set to take effect in May 2018.

It would require “clear and affirmative consent to the processing of private data by the person concerned,” according to the European Parliament.

But in Canada, data protection is more relevant than ever.

Proposed changes to the North American Free Trade Agreement include slackening rules on data sharing between the U.S. and Canada, which could allow Canadians’ data to be accessed by U.S. companies or governments.

The research was funded by Panorama, a German political magazine where Eckert works.

Comments