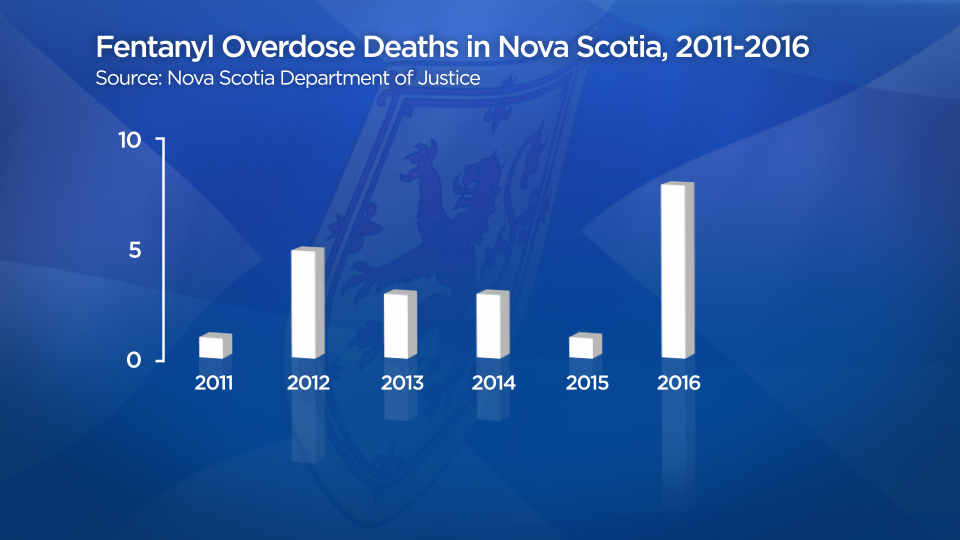

Nova Scotia’s government has made preparations to deal with the spread of non-prescription fentanyl in the province even as deaths related to the illicit drug hit a six-year peak in 2016, government documents show.

The trove of documents, released under Nova Scotia’s access-to-information legislation, show the provincial government’s plans to address what they see as an issue for public health officials.

“Illicit fentanyl has been identified by police in Nova Scotia and a small number of the overdose deaths have involved fentanyl,” reads a fact sheet prepared by the Department of Health and Wellness in November 2016.

“This is likely to become an increasing issue in the coming months.”

From 2011 to 2015 there was only one death connected to use non-prescription fentanyl in Nova Scotia.

But documents show that four of the eight confirmed deaths linked to fentanyl in 2016 were suspected to be from illicit sources — three deaths in Halifax and one in Cape Breton.

The Nova Scotia government believes that these deaths show a growing market for the drug, while the province’s own documents reveal the problem may be getting worse. In the first month of 2017 the governments own health officials suspect there have been two more deaths related to fentanyl.

READ MORE: At least 2,458 Canadians died from opioid-related overdoses in 2016: PHAC

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- Bird flu risk to humans an ‘enormous concern,’ WHO says. Here’s what to know

- Roll Up To Win? Tim Hortons says $55K boat win email was ‘human error’

- Election interference worse than government admits, rights coalition says

‘This is a national crisis’

The decision by the Nova Scotia government appears to have come, in part, because of British Columbia’s decision to declare a public health emergency in April 2016 due to the increase in opioid overdoses and opioid deaths in the province.

British Columbia has been the hardest hit by the fentanyl crisis, and if the pace of overdose deaths in B.C. continues, it will surpass 1,400 in 2017, a significant increase from the roughly 935 deaths recorded in 2016.

“This is a national crisis we’re dealing with,” said Theresa Tam, Canada’s Interim Public Health Officer, while speaking at a conference on opioids in Halifax on Tuesday.

“Even though the situation is worse on the West Coast, in the west-end of the country, everybody needs to be prepared.”

While Nova Scotia has not had numbers approach levels found out West, that doesn’t mean the Nova Scotia government isn’t viewing the drug as a concern.

READ MORE: Hamilton among cities seeking federal help in opioid battle

Documents show that one of the pieces of information stressed by the Nova Scotia government was that they were moving proactively to counter the threat of illicit opioids.

“We know these drugs are available here in Nova Scotia, and we’re acting now before this becomes a crisis in our province,” reads a document detailing ‘Key Messages’ for the Department of Health and Wellness.

But Robert Strang, Nova Scotia’s Chief Medical Officer of Health and the man helping lead the province’s response to opioid abuse, doesn’t seem to have a problem calling the situation what it is.

“It’s not wrong to call it a crisis and the illicit fentanyl and other illicit opioids are the immediate crisis,” said Strang in an interview with Global News on Wednesday. “We have longer-standing problems that are driven by over-prescribing of opioids… The use of opioids has been around for decades.”

WATCH: Saint John police look to protect themselves from fentanyl exposure

Experts in the opioid crisis point to the over-prescription of opioids as a factor that has led to Canada’s current situation.

Prescription opioid dispensing may have gone down in Western Canada said Benedikt Fischer, senior scientist at the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, but in places like Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, the rates continue to go up.

From 2011 to 2015 the province has averaged 60 opioid overdose deaths per year and while 2016 only saw 53 deaths, it was a year where Nova Scotia saw more illicit fentanyl on the streets.

“We didn’t really see it all but certainly in 2016 it’s starting to emerge both in police data and in some of the death data,” said Strang.

Challenges and solutions

The government has moved quickly to address the crisis with documents showing that naloxone, one of the drugs that can counteract the effects of an opioid overdose, has now been distributed throughout the province’s health centres.

But that quick reaction hasn’t come without its own problems. A government memo admits that the surge in fentanyl-related overdoses is “placing a tremendous strain on emergency responders and emergency rooms.”

Treating overdoses through naloxone may also pose an issue for the province in the future. While the government believes it’s relatively prepared with an established supply of naloxone, treatment is hard to predict. The amount of opioid ingested, the half-life of the opioid and the renal function can all change how much naloxone needs to be administered to treat an overdose.

Emails indicate that some officials have been concerned with the arrival of new synthetic opioids, such as U-47700, that can reportedly require multiple doses of naloxone.

Strang thinks Canadians need to rethink how we approach drugs in order to combat the opioid crisis. He says we need put in place the tools that will help people be safe — like naloxone — while trying to figure out longer-term solutions like access to treatment and decreasing the stigma around drug users.

“It’s not that we don’t have a problem,” he said. “It’s just that we’re trying to avoid things being a whole lot worse.”

— With files from Alexa Maclean and Andrew Russell, Global News

Comments