LinkedIn has lots of suggestions about people I might know. Why do they include two British sailors charged with sexual assault?

The professional social networking site made an effort at guessing people I might know. In this case it guessed wrong.

I don’t know Simon Radford (‘Physical trainer at Royal Navy’) or Joshua Finbow (‘Marine technician at Royal Navy’).

So how did they get suggested to me as people I might want to start networking with? It took me a moment to figure it out.

Last spring, when Radford, Finbow and two other British sailors were charged with sexual assault after an alleged incident at an air force base in Shearwater, N.S., I spent some time Googling all four defendants to see if I could find anything more about them. (The case is still before the courts.)

I had a few minutes free in Global’s Toronto newsroom, we had a reporter in Halifax pulling a story together, and I was trying to see if I could find something to add to the story. Not really, was the answer, and I moved on.

I was curious to know what social media traces the four sailors had left, but it turns out that I was leaving social media traces of my own without realizing it.

My LinkedIn account’s ‘People You May Know’ feature is a pretty good tour of people I was trying to interview for stories, not always successfully, between last spring and August.

It also includes a cousin in the U.S. who I only interact with on Facebook, someone I had a brief e-mail exchange with in January and people I know from university but don’t intersect with professionally. As well, there are a healthy number of media-relations people who I’ve never heard of or interacted with, but who have a professional reason to be curious about journalists.

Did I look at their LinkedIn pages? Did they look at mine? I don’t remember, or never knew in the first place, but apparently LinkedIn does. I suspect that on the back end there’s a bewildering crosshatch of people being outed to me and me being outed to other people.

“I find that appalling,” says former Ontario privacy commissioner Ann Cavoukian. “You should be able to look at things and browse at your own convenience without somebody out there knowing, and then feeding it back to you that these might be appropriate contacts in a particular case. We should be able to do things privately, including online.”

(Common sense suggests that I should have a throwaway LinkedIn account for researching people for stories – I may yet get around to that.)

LinkedIn did not respond to questions about the relationship between the ‘People you may know’ feature and a user’s browsing history.

Get daily National news

READ MORE: Our digital privacy coverage

What settings did I pick when I originally joined LinkedIn? To tell the truth, I couldn’t remember. So I started fresh, with a new account.

The first thing I noticed is that LinkedIn is very picky about what e-mail you enter in their system (unlike other online services that are happy with any functioning e-mail address that can accept a confirmation message). @globalnews.ca: rejected. @shawmedia.ca: rejected. @snappingturtle.net (a domain name I co-own): rejected. @gmail.com, on the other hand, was accepted.

Next step:

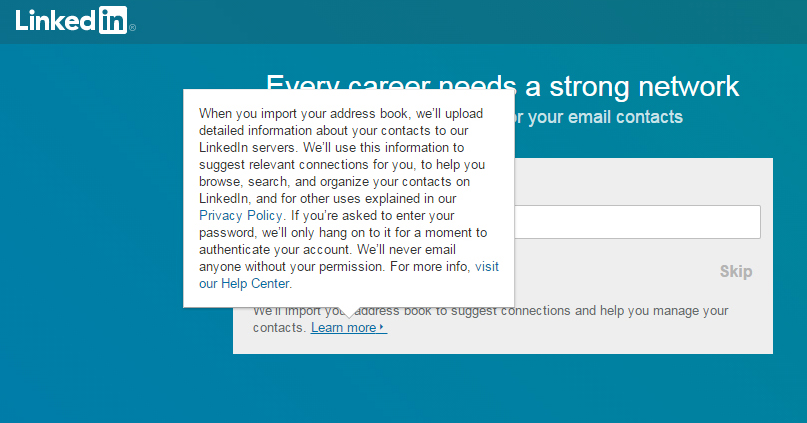

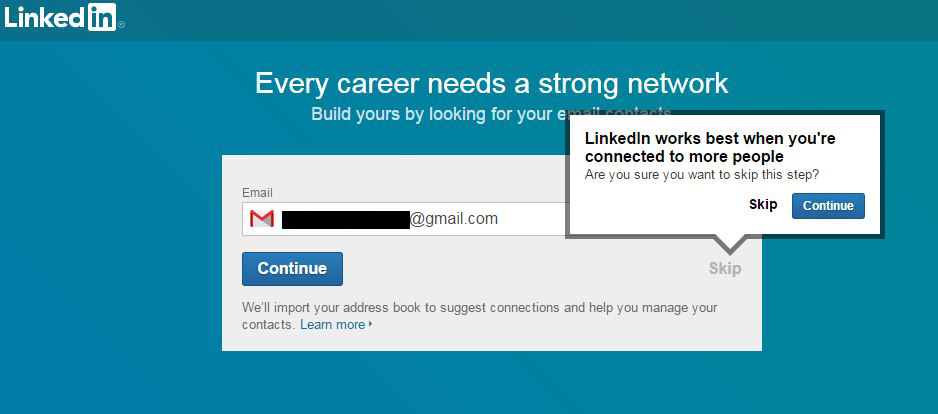

We’ll import your address book to suggest connections and help you manage your contacts, LinkedIn explains.

(It’s possible to skip this step, though LinkedIn does its best to nudge you in the other direction.)

I didn’t think I had an address book in Gmail, but Google is a many-layered thing, and it turns out I do – 95 people strong. Gmail keeps track of people I have frequent or recent e-mail contact with, it turns out. You may have one – have a look.

Who’s in mine? Well, the kinds of connections you’d expect in a personal e-mail account. With a bit of attention to domain names, it reveals all kinds of details, some that I don’t want filed away by anyone but me:

- Both of my older children’s elementary school teachers

- The financial institution my RRSP is in

Other e-mail addresses related to:

- An online store where I was buying wildflower seeds

- Another online store where I was buying appliance parts

- Another online store where I was trying to return defective baby overalls

- A bricks-and-mortar store where I was arranging to buy bricks

So, just by clicking the boxes, following instructions and not thinking all that much about their implications — which all too often is the way we interact with digital space — I’ve released a surprising amount of information, important and trivial, to LinkedIn about the details of my life — not just the work life and education chronology that’s public, but other layers as well.

LinkedIn spokesperson Suzi Owens describes this as “a one-time upload of your address book contacts, as well as their detailed contact information. We use this information to suggest relevant contacts for you to connect with, to help you browse, search, and organize your contacts on LinkedIn, and for other uses explained in our Privacy Policy. We’ll never email anyone without your permission.”

She added that “… synching is optional and a member can remove their address book and any other synched information whenever they like.”

We asked LinkedIn for an interview; they responded to questions by e-mail.

“It drives me crazy when law enforcement says ‘It’s only metadata,’” Cavoukian says. “You can learn far more from metadata, your e-mail contacts, who you connect with, on what basis — you can learn much more from that than from the actual communication in e-mail.”

“All of these concerns about privacy tend to be old people issues,” LinkedIn co-founder and executive chairman Reid Hoffman told an audience in Davos, Switzerland in 2010.

“The value of being connected and transparent is so high that the roadbumps of privacy issues are much lower in actual experience than people’s fears.”

Here’s the whole speech:

In light of Hoffman’s comments, how should LinkedIn users see the company’s attitude to their information? We asked them.

“At LinkedIn, our fundamental philosophy is “members first.” That value powers all of the decisions we make, including how we gather and respect your personal information. Members trust us with their information and we take that trust seriously,” Owens wrote.

“We are social animals, and we have a deep need to connect,” Cavoukian says. “But that doesn’t mean that you don’t have an equal need to have moments of privacy and reflection and seclusion. You need both. It’s a dated mindset that you can only have one or the other.”

“Young people are probably much more aware of how to protect their privacy through the appropriate privacy settings and measures than adults, who didn’t grow up digital. It’s a very different mindset.”

(A 2011 Canadian survey showed 18-to-34-year-olds were more likely to safeguard their digital privacy, by taking steps like password-protecting devices or choosing restrictive privacy settings, than people older than them.)

For Cavoukian, the key is balance.

“I’m on LinkedIn – I have thousands of connections,” Cavoukian reflects. “It’s a very useful tool. But you have to have an idea of where you want your privacy and data protected, who you’re happy to connect with professionally, and where you draw the line. You can, and must, have both.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.