NANAIMO, B.C. — Trevor Greene, once an elite athlete, is determined to leave behind his wheelchair.

“I’m psyched about the future… when I will be walking eventually and running and surfing and rock climbing,” he says.

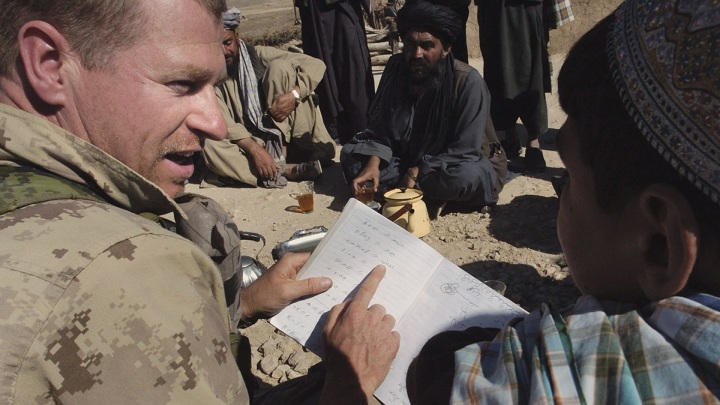

In March 2006, Greene was an army reservist captain serving a tour of duty in Afghanistan.

READ MORE: Afghanistan veterans find healing in their creative sides

He was trying to build bridges with the people of Afghanistan as part of a humanitarian mission.

He met with village elders and took off his helmet as a sign of respect. That’s when a 16-year-old took out an axe and smashed it over Greene’s head.

He was rushed to a hospital in Germany, but no one thought he would survive. He defied the odds.

“He’s got a really strong work ethic,” says his wife Debbie Greene. “I think that goes a long way with a brain injury. That internal drive is so critical.”

READ MORE: Army suicide rate 3 times higher than other branches of Canadian military

Under her watchful eye, Greene exercises for two hours every morning. That’s followed up with two hours of physiotherapy in the afternoon.

Researchers from Simon Fraser University have been watching Greene’s progress.

- Latest alleged Iranian regime official found in Canada wants his identity hidden

- Why Canadian beer cans are ‘almost impossible’ as tariffs near 1-year mark

- Jivani’s trip to Washington has some Conservative MPs scratching their heads

- Canada’s new Greenland consulate officially opens with patriotic ceremony

Dr. Ryan D’Arcy, a neuroscientist, first met Greene in 2009.

Get weekly health news

He was impressed with how far he had advanced. In 2010, he enrolled him in a study on neural plasticity.

Basically, he wanted to look at how rehabilitative efforts could help the brain retrain itself.

“When we talk to brain injury survivors,” says D’arcy, “the emphasis in recovery is that it’s a new elite sport.”

READ MORE: Invisible Wounds: Ways to retrain traumatized brains

Greene’s brain injury affects the movement of his lower limbs.

If he can retrain the brain to move those muscles in a different way, perhaps he can walk again.

That’s where the exoskeleton comes in — a wearable robot that moves Green’s hips and knees.

Two months ago, he took his first steps with the robot.

“It was the first time in the history of the world that someone who has a brain injury used an exoskeleton to help them walk further,” says D’Arcy.

This is a first because up until now, exoskeletons were only used on patients with spinal cord injuries.

Greene is unique in this study because he has a brain injury.

Given his determination, it is only fitting that it’s being called the Iron Soldier Project.

Dr. Carolyn Sparrey, a mechanical engineer and professor at Simon Fraser University, has been working on outfitting Greene with the exoskeleton to make sure it fits him.

She’ll also be monitoring how it impacts his overall health.

“So things like his blood pressure, his digestion, his sleeping,” says Sparrey, “this is all improved by being upright and mobile.”

Green’s wife hadn’t seen him walk in nine years.

“To see him walking at a normal gait was breathtaking. It was inspiring,” says Debbie Greene.

D’arcy hopes Greene will be walking without the exoskeleton within five years.

The goal is to get him to the base of Mount Everest.

Greene finds it hard to measure his progress.

“It’s hard to be objective about your own body,” the 50-year-old says.

It’s so far beyond what doctors predicted.

They didn’t think he’d live, but Greene is proving them wrong in so many ways.

Comments