Ontario’s announcement this week that it plans to sell certain kinds of beer in select grocery stores starting three months from now came as good news to some, but it also raised public health alarm bells.

Groups including the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse are calling on the province to adopt a provincial “alcohol strategy,” slow down its liberalization of alcohol retail regulations — and maybe change tack altogether.

“From a public health perspective, a move in this direction really is heading down the wrong road,” says Wayne Skinner, CAMH’s Deputy Clinical Director of Addiction.

Does greater access to alcohol mean greater likelihood of abuse and harms resulting from its consumption?

It’s complicated.

READ MORE: The fine print in Ontario’s new beer agreement

WATCH: Beer is coming to grocery stores – so what’s the catch?

Canada’s patchwork of provincial liquor laws makes it difficult to measure. The country’s been inching toward liberalization — from the partial privatization of liquor sales in Ontario, B.C. and elsewhere to the loosening of restrictions on buying booze in one province and taking it to another.

That worries Skinner.

“You need to be really careful about expanding alcohol availability.”

“These are unpopular opinions,” he admits. “But … from a public health perspective the goal should be, ‘How can we actually reduce the harms around alcohol consumption? How can we educate people around moderate drinking practices but also educate people not to drink?'”

Dan Malleck doesn’t buy it.

The Brock University health sciences professor and author of Try to Control Yourself: The regulation of public drinking in post prohibition Ontario calls these public health objections “histrionics.”

“It’s not like everyone in Alberta is drunk all the time,” he said.

“We have this utter fear of alcohol.”

READ MORE: Harper says it’s ‘ridiculous’ Canadians can’t bring alcohol across provincial borders

There is concerning evidence, however.

A 2011 study from the Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia found a positive correlation between the number of liquor stores per 1,000 residents and the rate of alcohol-related deaths: The more liquor stores there were in a given health region, the more people in that region died of alcohol-related causes.

Get weekly health news

“As the number of outlets in an area goes up, consumption goes up. And also alcohol-related deaths go up,” said Tim Stockwell, the centre’s director and the paper’s primary author.

“It’s not a huge effect, but it’s there.”

Ontario health officials have cited Stockwell’s study, concerned something similar could happen in Ontario.

But there are far more factors at play — including price, culture, education and socioeconomic inequities — determining the extent of alcohol abuse, misuse, addiction and deaths.

A 2013 study by the same B.C. Centre for Addictions Research found a much stronger price association: Higher alcohol prices meant fewer alcohol-related hospital admissions.

“Price is much more powerful than the density … of liquor outlets,” Stockwell said.

“So if you want to reduce problems and harm, particularly paying attention to the floor prices that the heaviest drinkers and the youngest drinkers gravitate towards, that’s where you get a lot of impact.”

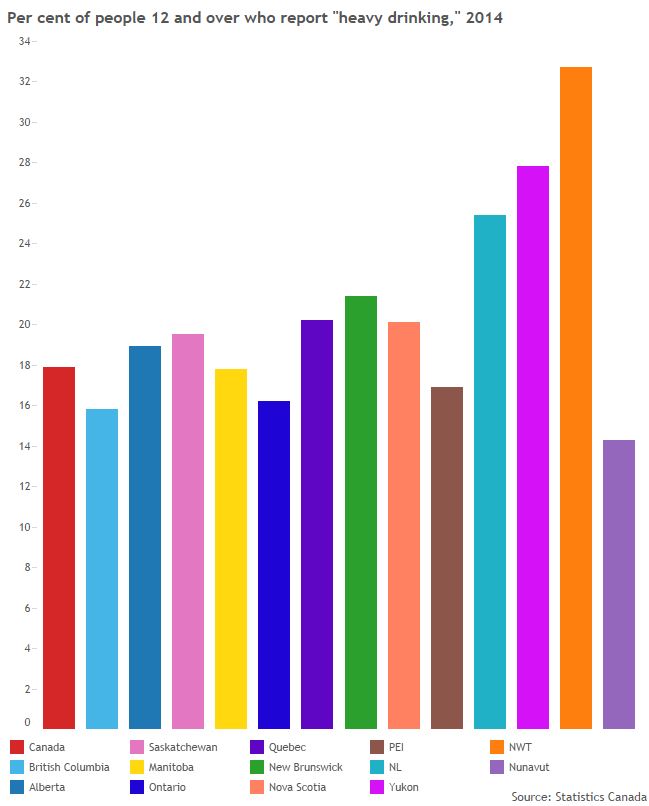

And provincial drinking rates don’t appear directly correlated to alcohol availability:

The Northwest Territories and Yukon have the highest rate of people who say they’re “heavy drinkers,” even though sales in both are largely restricted to government-owned stores.

Newfoundland and New Brunswick have heavier drinking rates than Quebec and Alberta, despite having more government-controlled liquor sales.

And high alcoholism rates in some rural areas are likely attributable to factors other than accessibility.

“Maybe people have less things to spend their money on in rural areas, the entertainment is less diverse and they perhaps have more restricted movements,” Stockwell said.

“I think one has to think … about helping communities be cohesive without the default … drinking occasions.”

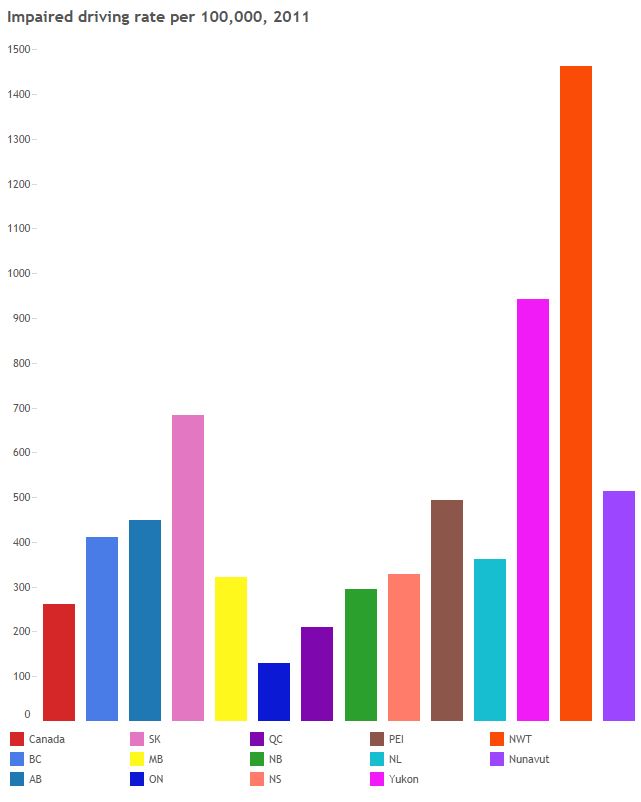

Impaired-driving rates don’t appear to correlate with alcohol deregulation, either:

The Northwest Territories, Yukon and Saskatchewan have significantly higher police-reported drunk driving rates than any other regions, despite having more government regulation of their liquor sales than Alberta, Quebec and, arguably, B.C.

Saskatchewan addressed its high drunk-driving rates with minimum alcohol pricing in 2010, Stockwell said.

“We have detected significant drops in impaired driving since then.”

Quebec is another counter-intuitive example: certain kinds of alcohol are much more readily available and the province has high overall alcohol consumption rates, but it has a lower rate of self-reported heavy drinking, according to Statistics Canada. That means there’s less binge drinking and more moderate consumption in the province.

“When alcohol was introduced in grocery stores in the ’70s, everybody expected there would be a high rise in heavy drinking — It did not occur,” said Catherine Paradis, senior research and policy analyst with the Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse.

“Quebec has a drinking culture that is different. Prevention is done way differently than elsewhere in Canada.”

Paradis cites a multi-million-dollar campaign educating Quebecois about binge drinking, which public health officials define as — brace yourself — more than five drinks at a time for men, and four drinks at a time for women.

Tackling problem drinking and alcohol-related illness and death goes beyond making it inconvenient to buy booze, Paradis said.

She also points to important regional differences in what people drink and when they drink it: Quebecois are most likely to drink wine and least likely to drink spirits, the inverse of the prairie provinces, according to a 2010 study Paradis co-authored. Maritimers report more binge drinking and are less likely to drink with meals.

“Drinkers from Québec, Ontario and BC show a drinking style that is closer to the Mediterranean culture, i.e., men and women in these provinces drink more often, drink more wine, drink less spirits, and drink during a meal more often than drinkers from the other provinces,” the study reads.

(That study also found women in the Maritimes drink coolers more than elsewhere in Canada.)

“Alcohol-related harms and outcomes are not simply related to availability,” she said.

“I worry [governments are] going to loosen the rules without making the necessary effort on the other side.”

A 2013 study evaluating Canadian provinces on their alcohol public health interventions recommended minimum pricing, government-controlled retail, limiting the “physical availability” of alcohol and limiting advertising that targets young people, among other things.

“There are so many economic, demographic and other factors that it’s not reliable or usual practice in policy research to make simple comparisons across different jurisdictions at one point in time,” Stockwell said.

“Also, there is no simple correlation between having a monopoly and having good policy – a monopoly only provides an opportunity for good policy which may not be taken.”

Comments