TORONTO – On Nov. 6, residents of Calgary enjoyed a balmy 16 C day. Though it was a bit cloudy and the winds had picked up by the evening, it was a nice reminder of the cooler days of summer. Fast forward seven days and Calgarians woke up to a frigid temperature of -20 C.

And let’s not forget the 28 cm of snow the city received in early September. Which was followed by the warmest October the city had seen in almost 50 years.

It’s a roller coaster of weather, and it’s not just limited to Calgary.

We’ve seen flooding in Calgary and Toronto. Ice storms in Quebec and Ontario. Temperature records broken in Winnipeg.

This week, Buffalo is seeing what will likely be record amounts of snowfall following a week of unprecedented lake effect snow. Some parts of the city are buried under almost 10 feet of snow. Ten feet. They have received their yearly snowfall over a few days.

- ‘Alarming trend’ of more international students claiming asylum: minister

- TD Bank moves to seize home of Russian-Canadian jailed for smuggling tech to Kremlin

- Why B.C. election could serve as a ‘trial run’ for next federal campaign

- After controversial directive, Quebec now says anglophones have right to English health services

READ MORE: PHOTOS: Best memes out of Buffalo during epic snowstorm

And what’s coming? Highs of 7 C in the next two days with rain.

Get breaking National news

It seems like weather extremes — or more specifically weather variability — is becoming more frequent. But is this really the case or are we living in an age where social media makes it appear that way?

“I’ve often said: The more you educate people about the weather, the more weather you get,” said Environment Canada senior climatologist David Phillips.

A perfect example is that tornado numbers appear to be on the rise. It’s not the large, destructive tornadoes that impact peoples’ lives, but rather weaker ones in far-off fields. With more people chasing them or using cell phones to capture them, the numbers are skewed.

Many people look to extreme weather events as a signal of climate change.

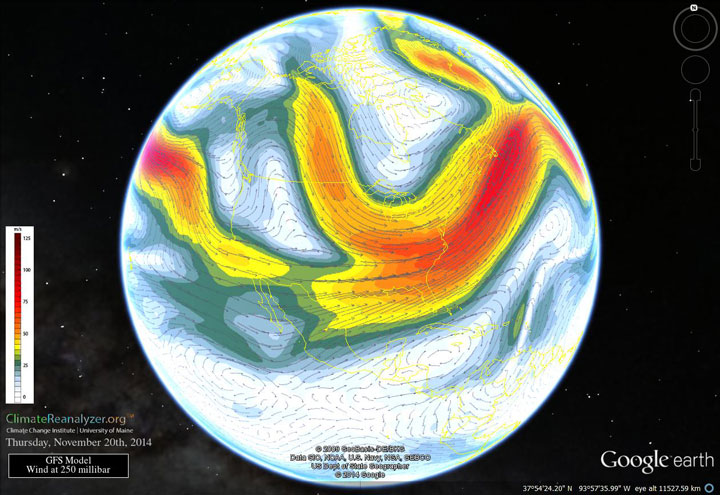

“There is all kinds of thoughts with climate change. That the potential there is for greater extremes and for greater swings in temperature. That the jet stream seems out of whack, it tends to be more loopy than straight,” Phillips said. “And I think a lot of people are suggesting that this is the way we will see climate in the future.”

The jet stream highly influences our weather. Its winds typically travel from west to east. However, lately it seems like there are “kinks” in it, where it rises high up into the north and then drops down again into the south. And that means it brings cold air along with it. The snow event in Buffalo is due to that influence as the Arctic air has met the relatively warmer waters of the Great Lakes.

Jennifer Francis is an atmospheric scientist and a research professor at the Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences at Rutgers University in New York. She’s studied the jet stream and believes that its meandering is due to the melting sea ice in the Arctic.

“Our hypothesis is that, as the Arctic warms so fast, it’s reducing the temperature difference between the Arctic and areas farther south,” she said. “And that temperatures difference is one of the main factors that drives the jet stream.”

As that difference gets smaller, there’s less force driving the winds of the jet stream. When that weakens, the jet stream is more easily influenced by other weather patterns — like Typhoon Nuri which raced across the Pacific in early November, landing here in North America and bringing freezing temperatures to the Prairies.

“We think that these sorts of very wavy patterns will happen more often, and that’s because the Arctic continues to lose its ice and continues to warm faster than the rest of the world,” Francis said.

Looking for extremes

Weather reporting seems to have taken on a sports-like mentality, where there’s a statistic for everything: the coldest day, the coldest temperature on that particular day, the most humid day, the hottest June, the windiest Fall, the month with the worst wind chill, the coldest midday temperature.

Phillips feels that weather is always variable, however he does concede that even he’s seeing a difference from the weather of his youth.

Southern Ontario was one of the most consistent areas when it came to weather, he noted. But over the past 10 years, there’s been much more variability: Farmers struggle to keep up as they experience the wettest growing season followed by the driest.

READ MORE: Here’s the damage extreme weather has dealt insurance rates this year

But Phillips says that perhaps the period on which we have based our “normal” — the 1950s to 1970s — wasn’t normal at all.

“Everything that we’ve done has been based on those decades — the infrastructure, the planning decisions, the building codes,” he said. “But some have suggested is that what we’re seeing now is really the norm.”

“The new normal is expect the unexpected,” said Phillips. “But in many ways, which is the more normal?”

Comments