Watch above: Imagine astounding the world by landing a spacecraft on a speeding comet and waiting to gather amazing data that could explain the very origins of live on earth, only to wonder if the batteries will go dead. Eric Sorensen reports.

BERLIN – A European probe has begun drilling into a comet to collect scientific data, but mission controllers said Friday that battery issues may make it impossible — at least for now — to access that information.

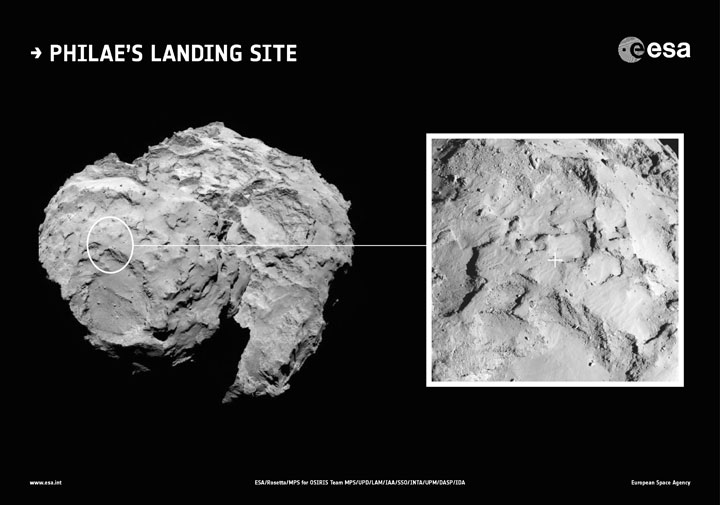

The Philae lander on Wednesday became the first spacecraft to touch down on a comet and has since sent its first images from the surface of the body, known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

But two harpoons that should have anchored the washing machine-sized Philae to the surface did not properly deploy when it hit the comet.

READ MORE: Listen: Philae probe lands on ‘singing’ comet

That caused the lander to bounce off the comet and drift through the void for two hours before touching down again. After a second, smaller bounce, scientists believe it came to rest in a shallow crater on the comet’s four-kilometre-wide body, or nucleus.

European Space Agency mission control still has not been able to locate the probe, but it’s believed to be next to a cliff that is blocking sunlight from its solar panels.

That means the probe has been operating on battery power, which is expected to soon run out.

Philippe Gaudon, an ESA project manager, said that by using that power, Philae was able to successfully deploy its drill and bore 25 centimetres (about 10 inches) into the comet’s surface to start collecting samples.

“So the mechanism has worked, but unfortunately we have lost the link and we have no more data,” he told reporters in an online briefing.

Scientists hope to be able to study the material beneath the surface of the comet, which is streaking through space at 41,000 mph (66,000 kph) some 311 million miles (500 million kilometres) from Earth. Since the material has remained almost unchanged for 4.5 billion years, it is something of a cosmic time capsule.

But Stephan Ulamec, head of operations for Philae, said right now it was unknown whether battery power would be sufficient to link back up with the probe.

“Maybe the battery will be empty before we get contact again,” he said.

Meantime, he said the probe is receiving “very limited power” from its solar panels and project engineers are trying to determine how they might move the panels so that they receive more sunlight.

Communication with the lander is slow, with signals taking more than 28 minutes to travel between Earth and Philae’s mother ship, the Rosetta orbiter flying above the comet.

Holger Sierks, the principal investigator for the Rosetta’s camera systems, said based on the way the probe bounced, he believes that they should have caught on film where it was somewhere around 500 metres above the surface of the comet.

“We should have seen the rebound and the rebound direction, which will give valuable information to the search team.”

That data has not yet come in, however, and specialists still need to comb an area of between one and two square kilometres to find Philae.

Even if Philae uses up all its energy, it will remain on the comet in a mode of hibernation for the coming months. The comet is on a 6 1/2-year elliptical orbit around the sun, and at the moment it is getting closer. So, in theory, Philae could wake up again if the comet passes the sun in such a way that the solar panels catch more light, Ulamec said.

Meanwhile, the Rosetta orbiter will also use its 11 instruments to analyze the comet over the coming months. Scientists hope the $1.6 billion (1.3 billion euro) project will help them better understand comets and other celestial objects, as well as possibly answer questions about the origins of life on Earth.

–David Rising contributed to this story

Comments