WATCH: A new report is blaming human activity for rapidly declining animal populations around the world. But, researchers say this pattern of loss can be reversed. Ross Lord explains.

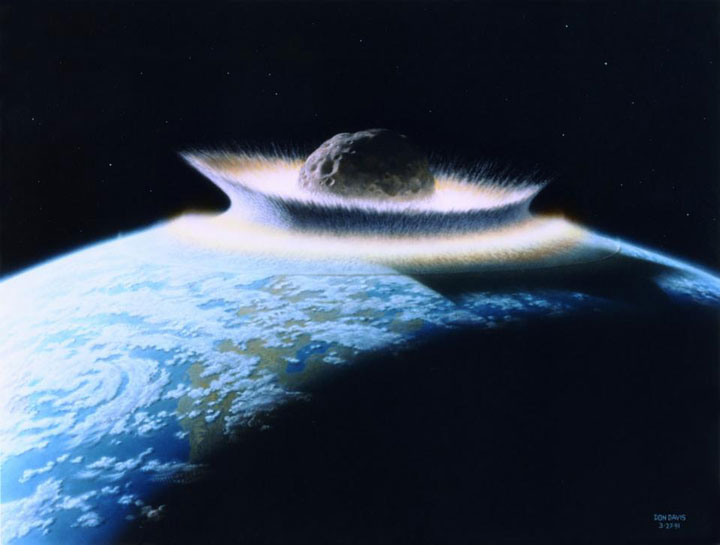

TORONTO – When we think of mass extinction, most of us envision a hurtling rock blazing across the sky, a massive fireball slamming into Earth covering the planet in a cloud of debris and killing off unsuspecting dinosaurs.

But what if, instead, we envisioned the gradual loss of tigers, rhinoceroses, elephants, and polar bears? What if, instead, one day we looked out our window to see 75 per cent fewer birds, squirrels or deer?

Already, we’ve lost around 97 per cent of the world’s tigers. In 2013, the western black rhino was declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the last one being seen in 2006.

A study that appeared in the journal Science Advances on June 19 concludes that we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction.

“There are examples of species all over the world that are essentially the walking dead,” Ehrlich said.

The study suggests that species are disappearing up to about 100 times faster than the normal rate between mass extinction events.

“If it is allowed to continue, life would take many millions of years to recover, and our species itself would likely disappear early on,” said lead author Gerardo Ceballos of the Universidad Autónoma de México.

The idea that humanity might be headed towards — or in the midst of — a mass extinction event might sound unbelievable to some. Others might think it a fear-mongering tactic by environmentalists.

However, though scientists around the world may disagree as to the rate of species we are losing, most agree that we are either at the start of a mass extinction event or in the middle of one.

What is a mass extinction?

In order to be considered a mass extinction, 75 per cent of known species must go extinct.

Get breaking National news

Earth has experienced five mass extinction events. The first was 445-440 million years ago where more than 80 per cent of all species were lost. The second was about 375 to 359 million years ago. Roughly 80 per cent of all species were lost in that event.

The third event — and the worst of the five — occurred 252 million years. Almost 95 per cent of the world’s species was wiped off the planet. Roughly 80 per cent of the world’s species was lost in the fourth event, 201 million years ago.

And then, the most notable of all extinction events occurred 65 million years ago when an asteroid slammed into Earth changing Earth’s climate dramatically and wiping out the dinosaurs.

“The common thing in all events, are major changes in the chemistry of the atmosphere, the chemistry of the oceans, and particularly, the carbon cycle,” Anthony Barnosky, professor of integrated biology, University of California, Berkeley said.

And that is just what’s happening now.

Shrinking populations

At the end of September, the World Wildlife Fund released its Living Planet Report 2014 stating that the population sizes of vertebrate species around the world had fallen by 52 per cent over the past 40 years.

READ MORE: Global wildlife populations drop more than 50 per cent in 40 years

“What makes this report interesting is that they’re monitoring the size of the populations,” Arne Mooers, professor of biodiversity at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia said.

“Extinction starts with the loss of population,” Mooers said. “This is like an entire shrinking of the biodiversity.”

Mooers said that we could avoid extinction by just sticking the animals that are threatened into zoos.

“But it would mean that our planet is very, very different.”

Mooers believes that the sixth mass extinction started with industrialization.

“These changes are not part of some natural cycle,” Mooers said.

He said that 99 per cent of what has existed on this planet has gone extinct. However, humanity’s progress — the taking over of Earth’s natural environment — has helped speed things along.

Barnosky agreed.

“The changes we’re causing on Earth today is more rapid than anything we’ve seen in the geological past, short of the asteroid strike,” he said. “It’s a real wake-up call.”

According to Barnosky, we are losing species far too fast.

“Depending on the numbers you use and how you do the calculations, somewhere between 10 and 100 times too fast. And even at the 10 end, it’s enough to cause a mass extinction between a century or two.”

Unlike Mooers, Barnosky believes that the extinction event started between 50,000 years ago (in Australia) and 12,000 years ago (in the Americas). It then stabilized until about 200 years ago.

Hope for the future

Just because we are increasing the rate of extinction doesn’t mean that it’s all a lost cause, though.

“Because these things take time, they’re not inevitable,” Mooers said.

Stuart Pimm of Duke University believes that we’re on the verge of a mass extinction event and that we’re driving species to extinction at a rate 1,000 times faster than would naturally occur.

“If the current rate continues for 50 years, maybe 100 years, we are indeed at a risk of losing a third to a half of all species,” Pimm said.

However, Pimm said that though this is unsettling, there are also success stories around the world as countries attempt to create healthy, balanced environments, such as Brazil’s efforts to reduce its deforestation.

That means, by changing how we interact with nature, we can stop the rapid loss of species around the globe.

“That’s where the hope lies: that we do know how to save species when we put our minds to it,” Barnosky said. “We do have a short window of opportunity where we can avoid this sixth mass extinction, but if we don’t take advantage of that opportunity now, it may well be too late.”

Comments